Immediate Antecedents of Intentions for Having Children in Southeast Iranian Women

Article information

Abstract

Background

Over the last decade, Iran has experienced a declining birth trend. Identifying the proximate determinants of fertility intentions among married women is informative for population studies. This study aimed to examine the importance of three immediate antecedents of fertility intention.

Methods

We invited 1,100 married women to complete a well-validated questionnaire based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). The sampling framework consisted of visitors attending hospitals in two cities in southeastern Iran. Intention for having children was measured using the item “Do you intend to have a/another child during the next 3 years?” Attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were measured using eight, three, and three items, respectively. Structural equation modeling was used to specify the model and to test the predictive ability of the TPB constructs.

Results

The response rate was 90.7% (N=998), and the mean±standard deviation age of the respondents was 34.8±7.4 years. More than 50% of the respondents reported intending to have a child in the next 3 years. All three TPB model constructs showed significant associations with fertility intentions. The standardized beta coefficients for attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were 0.74, 0.41, and 0.55, respectively.

Conclusion

The TPB model showed that psychological mechanisms play an important role in predicting the childbearing intentions of married women in Iran. Of the three TPB constructs, attitude was the strongest predictor of the intention to have a child.

INTRODUCTION

According to the forecasting analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study, by 2050, a total of 151 countries are projected to have below-replacement fertility, meaning a total fertility rate (TFR) below 2.1 births per woman [1]. The declining trend of TFR is not only limited to developed countries; in a recent review, a declining trend was reported in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) [2]. Lebanon, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Tunisia, and Turkey have already experienced a belowreplacement TFRs [2].

Iran, the second-largest country in the Middle East, reached replacement fertility levels at the beginning of the 21st century. By 2011, 21 of the country’s 31 provinces had a TFR below the replacement level [3]. According to a United Nations’ report, Iran is projected to see substantial growth in the percentage of the older population by 2050, making it the only country in the MENA region where more than 30% of its population will be elderly [4]. Furthermore, between 2015 and 2050, Iran is the second-fastest aging country in the world after South Korea in terms of the growth of the older population percentage [5]. Indeed, some have referred to the population crisis in Iran as an “emerging demographic tsunami.” [6] Accordingly, low fertility has garnered considerable attention from policy-makers and researchers in Iran, as well as those in many other below-replacement TFR countries. As Iranian society moves towards modernity, people’s values are changing [7]. Cultural factors, such as changes in women’s dispositions towards marriage and childbearing, the weakening of traditional values, and a tendency toward individualistic norms and lifestyles, all negatively impact fertility intentions [8].

There are several approaches to explaining the reasons underlining the declining fertility trend in countries with a low TFR [9]. One perspective analyzes the determinants of fertility at three levels: micro (individual), meso (group), and macro (policy) [10]. At the micro level, the emphasis is on individuals’ fertility behavior and how it is formed [10]. Interest in micro level research has increased in recent decades, and psychology and behavioral sciences are major disciplines that fuel this paradigm shift [9]. In this regard, the theory of planned behavior (TPB), “one of the most applied theories in the social and behavioral sciences,” [11] continues to offer an empirical framework in the field of fertility research [9]. Proposed by Ajzen [12], the TPB depicts how a person’s thoughts affect their behavior and explains how our behavioral intentions and behaviors are shaped by a combination of three core components: attitudes toward a certain behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Attitude toward fertility is the degree to which an individual has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation with respect to having a/another child [13]. Subjective norm refers to a person’s perception of significant others’ expectations of them having a/another child [13]. Finally, perceived behavioral control means an individual’s subjective perception of the ease or difficulty of having a/another child [13].

Many empirical studies on childbearing intentions have employed TPB to determine the determinants of fertility behaviors. However, most have evaluated the role of each of the three aforementioned constructs (i.e., attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) as a whole rather than item by item [14,15]. Thus, policy-makers and researchers require more accurate and detailed information about beliefs that influence fertility intentions.

In our study, we used a simple TPB model to elicit the antecedent beliefs that underlie the formation of fertility intentions among Iranian women.

METHODS

1. Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted during the first half of 2022 in two major cities in Kerman Province, southeast Iran. We invited 1,100 women to complete a self-administered questionnaire. To obtain a representative sample of city residents, following our previous studies, we invited female visitors who had been referred to hospitals [16,17]. The inclusion criterion for this study included married women aged 18–49 years. Women who did not provide informed consent or had infertility issues were excluded. Participants were approached and invited to complete a self-administered questionnaire in a private area of the hospital lobby. A convenience sampling method was used in this study.

2. Measurement Tool

The validity and reliability of the measurement tool were confirmed by a previous study conducted on Iranian women of reproductive age [18]. Our questionnaire consisted of two parts: demographic characteristics (i.e., age, education, employment, number of children, and marriage age) and the constructs of the TPB (i.e., intention, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) [19].

To measure intention, we used the item “Do you intend to have a/ another child during the next 3 years?” Attitude was measured using eight items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Five of these items were related to childbearing benefits (e.g., “It increases the intimacy between me and my husband”), while three items evaluated childbearing costs (e.g., “Our financial problems will get worse”). Three items were reverse coded, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude toward childbearing.

Subjective norms were measured through three items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). A sample item is “According to my parents, I should have another child (or first child).” Higher scores indicated that subjective norms supported childbearing.

Perceived behavioral control was measured using three items measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very little) to 5 (very much). A sample item is “How much do you think your economic situation and income will affect your decision to have a child in the next 3 years?” We reversed the scores of the three items for this construct such that higher scores indicated greater control over reproductive behavior.

The Cronbach’s α for the three domains (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) were 0.82, 0.84, and 0.63, respectively, with an average of 0.78. This value is above the threshold level of 0.7, indicating satisfactory internal consistency [20].

3. Ethical Considerations

We explained the nature and goals of the study to all potential participants and assured them their responses would remain confidential. To provide more assurance, participants were asked to place the completed questionnaires into a sealed ballot box. All participants provided informed oral consent before answering the questions. The study protocol was approved by the Kerman University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee to ensure that the study adhered to ethical standards (IRB approval no., IR.KMU.REC.1400.539).

4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of demographic variables and scores for each item and construct were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). IBM SPSS AMOS ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp.) was used to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). The factor loadings for each item in the three constructs were calculated and items with low factor loading values (<0.35) were excluded from the model [21].

SEM was utilized to specify the model and test the predictive ability of the TPB constructs and each questionnaire item to predict childbearing intentions. The maximum likelihood approach was applied to estimate the parameters of the model [22]. Childbearing intention was considered the endogenous variable impacted by the three constructs of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control as exogenous variables.

The adequacy of model fit was calculated using the following indices: chi-square fit index (χ2/degrees of freedom [df ]), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI). The acceptance value for model fit indices were chi-square ratio (χ2/df) ≤3.0, RMSEA <0.8, CFI >0.9, and AGFI >0.8 [23].

RESULTS

1. Participant Characteristics

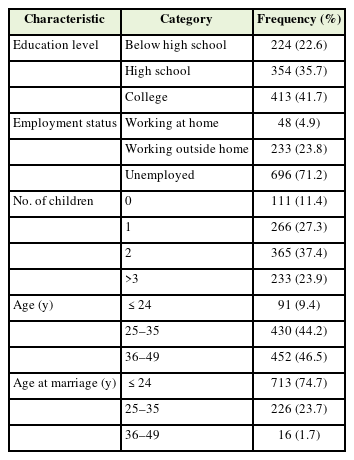

In this study, 998 married women completed the questionnaire, with a response rate of 90.7%. The mean±standard deviation (SD) age of the participants was 34.8±7.4 years and the mean±SD age at marriage was 21.9±5.2 years. Most participants (76.8%) were high school or college graduates (n=767), and the mean±SD number of children among the participants was 1.8±1.3. Table 1 presents the demographic variables.

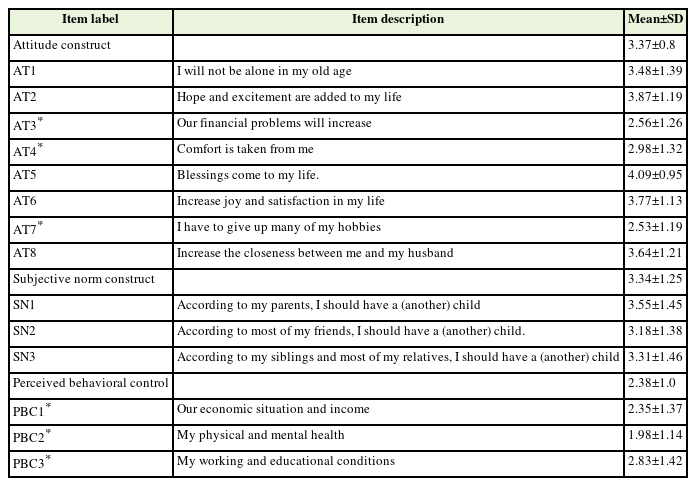

More than half (52.05%) of respondents declared that they intended to have a child within the next 3 years. Table 2 lists the means and SDs of the TPB constructs and items. The attitude construct and its fifth item (labelled “AT5”) had the highest mean value (3.37±0.80 and 4.09±0.95, respectively). In contrast, the perceived behavioral control construct and its second item (labelled “PBC2”) had the lowest mean (2.38±1.0 and 1.98±1.14, respectively).

2. Measurement Model

Based on CFA, the SEM showed that the measurement model fit the data well based on the measured indices (χ2/df=2.62, P<0.001, AGFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.04, and CFI=0.98), while two items (AT3 and AT7) were excluded from the model owing to low factor loading values (i.e., <0.35).

3. Structural Equation Modeling

Attitude (β=0.74, P<0.0001), subjective norms (β=0.41, P<0.0001), and perceived behavioral control (β=0.55, P<0.0001) all positively and significantly predicted the intention to have a/another child during the next 3 years (Figure 1).

Final model of childbearing intention based on theory of planned behavior; AT, attitudes; SN, subjective norms; PBC, perceived behavior control. E in a circle denotes measurement error of that latent variable.

Attitude was the strongest predictor of childbearing intentions, explaining 55% of the variance in childbearing intentions in the model. The highest path coefficients among the observed variables of each the three separate latent constructs of attitude (six observed variables), subjective norms (three observed variables), and perceived behavioral control (three observed variables) were observed in AT6 (“increase joy and satisfaction in my life”), SN3 (“satisfy siblings and relatives’ desire for a/another child”), and PBC3 (“my working and educational conditions”), respectively.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the proximate psychological mechanisms underlying childbearing intention helps us understand what is going on in people’s minds regarding having children [24]. In this way, our path for designing interventions and developing evidence-based population policies will become clearer. In this study, we restricted our use of the TPB to the three immediate psychological antecedents of the fertility intention of married Iranian women [25]. The study findings revealed that, in Iranian culture, all three constructs of the TPB (i.e., attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) have a detrimental role in the childbearing intention of married women. Our findings also showed that a higher percentage of Iranian women intended to have children in the future than women in European countries, including Russia (14.1), Italy (22.6), Germany (30.4), France (47.9), and Hungary (48.9) [13].

Among the attitude items, the highest mean values belonged to “blessings come to my life” and “hope and excitement are added to my life.” According to Islamic beliefs, children bring their own “blessing” with them. The word equivalent to blessing in Islam is barakah, “an invisible blessing that manifests itself as an increase that cannot be calculated in material terms encompassing the whole human affairs.” [26] This belief gives Muslims an inherent positive attitude toward having children, which is unfamiliar in the modern era [26]. On the other hand, the lowest mean score of the attitude items was related to the phrase “I have to give up many of my hobbies.” Although the individualistic thinking of Western culture has penetrated Eastern countries, this finding shows that Eastern mothers still do not consider having children an obstacle to their enjoyment of leisure activities [2].

The scores of the subjective norms items showed that parents have a greater influence on the mentality of married women than do friends and relatives. Therefore, parents can be a driving force in strengthening their intention to have children in the younger generation. Findings from a German longitudinal study similarly showed that parents are key normative referents influencing the fertility intentions of adult children [27].

The greatest perceived barrier to the decision to have a child was the individual’s general physical and mental health. In the Generations and Gender Survey conducted in European countries, which have a better economic situation than most of them, the financial situation was the most important control factor [25]. According to Ciritel et al. [28], financial status is not the issue; what matters is the conviction of believe that one has the financial resources to raise a child.

The SEM showed that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were consistently and significantly associated with childbearing intention. Attitude was the most important determinant of fertility intention, followed by perceived behavioral control and subjective norms. Among the attitude items, “increase joy and satisfaction in my life” was the strongest determining manifest variable. Although Iranian women’s tendencies toward the norms of Western cultures are slowly emerging [7,15], Iran remains a traditional society where childbearing and family values are important [29]. According to the SEM model, siblings and relatives are the most important influential subjective norm in women’s reproductive decision-making processes, and the strongest control beliefs were related to working and educational conditions. However, the importance of the three immediate antecedents of fertility decisions varies by country, and pro-natalistic policies may not be applicable to other countries [25]. For example, in Bulgaria, the strongest determining factor was perceived behavioral control [30], in China, the domain of attitudes played the most important role [31], while in Germany and Italy, perceived behavioral control had no statistically significant effect on the intention to have a child in the future [13]. On the other hand, subjective norms work as a double-edged sword. In countries with low fertility rates, close friends and relatives may encourage couples not to have children [30] and in traditional societies such as Iran, the reverse is still true [15]. According to Nauck and Klaus [32], the overall value assigned to children is lower in more affluent low-fertility countries. Normative pressure does not develop overnight and is the result of years of ideological changes that are less influenced by policies; meanwhile, the attitude that represents the internal evaluations of individuals toward childbearing is more prone to be affected by general policy settings [30]. Therefore, in a situation where traditional culture has been overshadowed by individualism and modernity, policy-makers should pay close attention to cultural factors and ideological issues (e.g., value orientations and religion) in their planning to promote childbearing.

In conclusion, attitude was the strongest proximate predictor of fertility intentions among married women. The TPB model showed that, in Iran, pro-natalistic policies should consider the psychological mechanisms underlying childbearing intentions.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.