|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Volume 43(2); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Primary dysmenorrhea (PD) is a common, disregarded, underdiagnosed, and inadequately treated complaint of both young and adult females. It is characterized by painful cramps in the lower abdomen, which start shortly before or at the onset of menses and which could last for 3 days. In particular, PD negatively impacts the quality of life (QOL) of young females and is the main reason behind their absenteeism from school or work. It is suggested that increased intrauterine secretion of prostaglandins F2α and E2 are responsible for the pelvic pain associated with this disorder. Its associated symptoms are physical and/or psychological. Its physical symptoms include headache, lethargy, sleep disturbances, tender breasts, various body pains, disturbed appetite, nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhea, and increased urination, whereas its psychological symptoms include mood disturbances, such as anxiety, depression, and irritability. While its diagnosis is based on patients’ history, symptoms, and physical examination, its treatment aims to improve the QOL through the administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hormonal contraceptives, and/or the use of non-pharmacological aids (e.g., topical heat application and exercise). Patients must be monitored to measure their response to treatment, assess their adherence, observe potential side effects, and perform further investigations, if needed.

Dysmenorrhea is defined as painful menstrual cramps of uterine origin, and considered as one of the most common gynecological disorders among females of childbearing age [1]. Although it is a common condition, it is usually underdiagnosed, since most females do not seek medical attention [2,3]. In accordance with its pathophysiology, it is classified as either primary or secondary dysmenorrhea (SD).

Primary dysmenorrhea (PD)—defined as spasmodic and painful cramps in the lower abdomen that begin shortly before or at the onset of menses in the absence of any pelvic pathology—is one of the most common complaints in both young and adult females [4]. Its onset occurs mainly during adolescence, within 6 to 24 months after menarche. Dysmenorrheic pain has a clear and cyclic pattern, which is typically severe during the first day of menses and lasts up to 72 hours [5]. Despite its high prevalence and impact on daily activities, it is often inadequately treated and even disregarded, given that, many young females prefer to suffer silently, without seeking medical advice. Females consider PD an embarrassment and a taboo, and also perceive the pain as an inevitable response to menstruation, that should be tolerated [1,6]. Primary healthcare providers commonly encounter females with dysmenorrheic complaints [7] and thus play a substantial role in diagnosing, educating, reassuring, and providing them with the therapy required for optimizing the overall treatment outcomes of PD [7-9]. This review focuses on the high prevalence and negative influence of PD on young females’ quality of life (QOL), and aims to provide primary health care providers, with an updated evidence-based perspective on the diagnosis and recommended treatment modalities for managing PD. Table 1 summarizes relevant information about this disorder.

In contrast, SD originates from a pathological disorder, such as endometriosis, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, adenomyosis, endometrial polyps, ovarian cyst, congenital anomalies, and complications of intrauterine contraceptive devices [3,10]. It is associated with diffused or constant pain, that does not necessarily occur during menstruation [10] and is usually detected in older females (>24 years) with no history of dysmenorrhea [11]. Females with SD often have clinical features that distinguish their condition from PD. These include a large uterus, pain during sexual intercourse, and resistance to effective treatment [12,13]. Endometriosis is considered one of the most common causes of SD, and is described as the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus. Hence, the diagnosis and treatment of SD are determined based on the underlying pelvic pathology [14].

The worldwide prevalence of PD ranges from 45% to 95% in females of reproductive age, with 2% to 29% experiencing severe pain [10,15]. This variation in the rates may be explained by the differences between the methodologies used to assess PD, the selected population, age groups, ethnicity, and pain perception differences among communities. A greater prevalence (70% to 90%) was generally reported among younger women (<24 years) [16].

Aside from physical health, dysmenorrhea disturbs the QOL and productivity of young females [10,16-18]. Prior studies have shown that PD is considered as one of the leading causes of absenteeism from school or work, translating to a loss of 600 million hours per year, with an annual loss of $2 billion in the United States [4]. The rate of school absenteeism ranged between 14% and 51% among females with PD [19]. During menstrual periods, class attendance was reported to decrease by 29% to 50% [19]. A study conducted in Palestine has shown that more than half of university students with dysmenorrhea tend to skip university classes due to painful menses [20]. In addition, a study from Hong Kong has shown that young women with PD had the lowest QOL score in the pain domain [21]. This was also supported by a study conducted in Turkey, which reported a lower perception of QOL among adult females [19].

Although the pathophysiology of dysmenorrhea has not been fully elucidated, current evidence suggests that the pathogenesis of dysmenorrhea is due to the increased secretion of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in the uterus during endometrial sloughing. These prostaglandins are involved in increasing myometrial contractions and vasoconstriction, leading to uterine ischemia and production of anaerobic metabolites. This results in the hypersensitization of pain fibers, and ultimately pelvic pain [10,15].

Prostaglandins are synthesized through the arachidonic acid cascade, mediated by the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway. Arachidonic acid synthesis is regulated by the level of progesterone, through the activity of the lysosomal enzyme phospholipase A2. The progesterone level peaks during the middle of the luteal phase—the latter phase of the menstrual cycle—that occurs after ovulation. If conception does not occur, this results in degeneration of the corpus luteum and a decline in the circulating progesterone level. This rapid decline in the progesterone level is associated with endometrial sloughing, menstrual bleeding, and the release of lysosomal enzymes, leading to the generation of arachidonic acid, and therefore, the production of prostaglandins [1,22].

Females with regular menstrual cycles have elevated endometrial prostaglandin levels during the late luteal phase. However, several studies that measured prostaglandin concentrations in the luteal phase, through endometrial biopsies and menstrual fluids, revealed that dysmenorrheic females have higher levels of prostaglandins than eumenorrheic females [1,22,23]. Consequently, menstrual cramps, pain intensity, and associated symptoms are directly correlated with higher concentrations of PGF2α and PGE2 in the endometrium [24].

PD pain usually starts 1 to 2 days before the onset of menses or just after the menstrual flow [3,25], with pain typically lasting for 8 to 72 hours [3]. In addition to lower abdominal/pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea is usually associated with common symptoms, that can be categorized into two main dimensions: physical and psychological symptoms. The commonly experienced physical symptoms are systemic, gastrointestinal, and elimination-related. The systemic symptoms include headache, lethargy, fatigue, sleepiness/sleeplessness, tender breasts, heavy lower abdomen, backache, in addition to painful knees and inner thighs, myalgia, arthralgia, and swollen legs. The gastrointestinal symptoms include an increase or decrease in appetite, nausea, vomiting, and bloating, while the elimination-related symptoms comprise constipation, diarrhea, frequent urination, and sweating [3,25].

Regarding the psychological symptoms, dysmenorrheic females may experience mood disturbances such as anxiety, depression, irritability, and nervousness [3,18,26,27]. It was reported that depression, anxiety, and excess somatic symptoms were three-fold higher in females with dysmenorrheic pain [11]. The co-occurrence of dysmenorrhea along with psychological symptoms could suggest a neurological brain disorder that contributes to menstrual pain, whereas the hereditability of both PD and psychological symptoms could reflect a shared genetic variance [28].

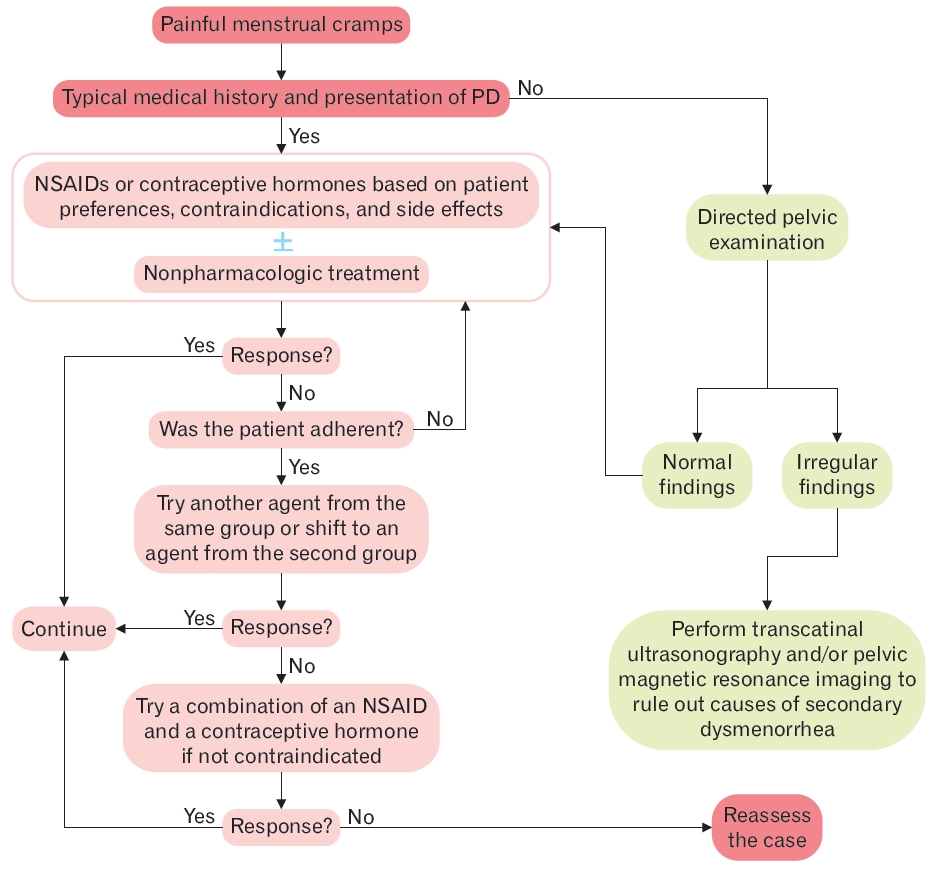

The diagnosis of PD is made mainly by retrieving a focused medical history and performing a physical examination to exclude the presence of pelvic pathology, as shown in Figure 1 [10,12,29,30]. The initial evaluation of PD involves obtaining relevant medical, menstrual, gynecological, and sexual history [13,30]. The focused medical history to be obtained includes, but is not limited to, the following information: age at menarche; regularity and duration of menstrual bleeding; abnormal vaginal discharge; onset and duration of symptoms relevant to the age of menarche; menstrual cycle; location of pain; and associated systemic symptoms [12] Furthermore, patients should be asked about their sexual activity and history of sexually transmitted diseases [12]. Since females with typical symptoms of PD can be diagnosed solely on the basis of their medical information, without any physical or pelvic examination, empiric treatment, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or oral contraceptives should be initiated [12,13,30]. However, a pelvic examination should be conducted on sexually active females experiencing symptoms of sexually transmitted diseases or pelvic inflammatory disease, or those with severe dysmenorrhea.

SD should be suspected if the patient reports an immediate or delayed onset of dysmenorrhea after menarche; severe symptoms associated with abnormal menstrual bleeding; irregularities and worsening of symptoms; dyspareunia, family history of endometriosis; or conventional therapy response failure [12,13,29]. The presence of any such symptoms mandates the necessity of a pelvic examination, and in some instances, performing transvaginal ultrasonography, or magnetic resonance imaging. Normal pelvic examination findings may also confirm the diagnosis of PD [12,13,30].

The main aim of PD treatment is to provide dysmenorrheic females with adequate pain relief that permits them to perform their usual activities, improves their QOL, and decreases their academic or work-related absenteeism [13,30]. Pharmacological as well as non-pharmacological complementary and alternative therapies are potential options for managing PD [29]. The first-line therapies recommended for treating PD are NSAIDs and hormonal contraceptives, since they inhibit the production of prostaglandins, that are directly correlated to menstrual pain and its associated systemic symptoms [12,13,25,30].

For females with a typical medical history and presentation of PD, it is preferred to initiate empiric therapy with either NSAIDs or hormonal contraceptives, as recommended by the American Academy of Family Physicians [12]. This is also supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [30] and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada [13]. However, there is no evidence favoring the efficacy of either NSAIDs or hormonal contraceptives over the other. If treatment with one modality fails or proves to be inadequate after a period of 3 to 6 months, the patient’s adherence to the therapy must be assessed before switching to the other modality [13,30]. A combination of NSAIDs and hormonal contraceptives is reasonable, only if the patient remains symptomatic on either drug class alone [12,13].

Furthermore, to optimize treatment efficacy and ensure patient satisfaction and adherence, clinician-patient shared decision-making is key to the optimal management of PD. Therefore, to provide patient-centered care, dysmenorrheic females should be educated about dysmenorrhea, its treatment options, and potential adverse effects, for enabling them to decide. Clinicians should consider the patient’s choice, preferences, desire for contraception, potential adverse effects, and contraindications to hormonal therapy [10,12,13,29-31].

NSAIDs are cost-effective analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents, most commonly used for managing PD [13,32-35]. They are considered the cornerstone in the management of dysmenorrhea, since they inhibit the action of cyclooxygenase, which in turn, inhibits the production of prostaglandins [10]. Therefore, NSAIDs are recommended as the first-line therapy in females who prefer using analgesics or when contraceptives are contraindicated [12,13,30].

Based on available evidence, there is no superiority of a certain NSAID formulation over the other, but various NSAIDs have comparable efficacy and safety in managing PD [5]. A systematic review of 80 randomized controlled trials that included 5,820 females was conducted to determine the efficacy and safety of NSAIDs in PD. It was concluded that NSAIDs were 4.5 times more effective than a placebo for pain relief (odds ratio [OR], 4.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.76–5.09), more than twice as effective as paracetamol (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.05–3.43), and were not superior for pain relief. 33) However, NSAIDs were also associated with adverse effects (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.11–1.51), including adverse gastrointestinal effects (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.12–2.23) and adverse neurological effects (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.12–2.23) [33].

The timing of administering the NSAID predicts its efficacy. For optimal treatment efficacy and safety, NSAIDs should be initiated 1 to 2 days before the predicted onset of menses, administered with meals to decrease adverse gastrointestinal effects, with a regular dosing regimen, and continued throughout the first 2 to 3 days of bleeding [13,30,36]. It was established that the initiation of NSAIDs before COX-2 cascade induction results in complete suppression of prostaglandin synthesis. Hence, the delay in the intake of NSAIDs produces gradual or incomplete suppression [36]. If a patient does not improve with a certain NSAID, its substitution with that of a different class is an alternative therapeutic option [12,30]. Although most females respond well to NSAID therapy, it was reported that 18% did not respond adequately to them [34]. Females who are unresponsive to NSAIDs may be switched to hormone-based treatments and/or non-pharmacological therapy [34].

Hormonal contraceptives are also considered first-line therapy for the management of dysmenorrhea, unless contraindicated. They are usually recommended for dysmenorrheic females who need contraception, for whom the use of contraceptives is acceptable, or for those who cannot tolerate or are not responsive to NSAIDs [12,13,30].

Hormonal contraceptives are proven to suppress ovulation and endometrial proliferation, consequently blocking the production of prostaglandins [37]. Hormonal therapy used in managing PD includes methods such as combined oral contraceptive (COC), contraceptive transdermal patches or vaginal ring, a levonorgestrel intrauterine system, and subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [38], proven to be effective in managing PD. However, since each method has its specific benefits and adverse effects, the decision for selecting a method depends on patient preferences, ease of administration, cycle control, costs, the profile of side effects, and availability [13,30,39]. Furthermore, clinicians should guide females in choosing hormonal contraceptives and ensure their medical eligibility for contraceptive use, to prevent the occurrence of venous thromboembolism and breast cancer [40,41].

It was reported that from among the hormonal contraceptives, the COC of estrogen-progestin has been the most common method utilized by dysmenorrheic females. In a longitudinal epidemiological study, COC was shown to significantly decrease the severity of PD [39,42]. However, the rate of use of COCs among dysmenorrheic females has not yet been established, although a study has shown that the majority of females take COCs for pregnancy prevention, and only 14% use them for non-contraceptive reasons, including acne, as well as primary and SD [43].

Acetaminophen is a reasonable pharmacological analgesic for dysmenorrheic patients who do not desire hormonal contraceptives and cannot tolerate NSAIDs for their gastrointestinal disturbance [44]. Since it has a weak COX inhibitory effect, it reduces prostaglandin production [45] and is considered a safe analgesic with tolerable gastrointestinal side effects [45]. Nevertheless, several studies that investigated the efficacy of different therapies in the management of PD have revealed that acetaminophen has lower efficacy compared to NSAIDs and hormonal contraceptives [4,33,46-50]. Hence, it is preferred only for mild-to-moderate dysmenorrheic pain.

The use of non-pharmacological interventions is common among dysmenorrheic females. A recent meta-analysis, comprising 12,526 dysmenorrheic females, revealed that 51.8% adopted different non-pharmacological measures to cope with their menstrual pain [48]. For managing dysmenorrhea, several non-pharmacological interventions have been recommended, that can be either employed solely as an alternative therapy or adopted in combination with NSAIDs or COCs as a complementary therapy [10,12,13,30]. These interventions were hypothesized to reduce menstrual pain by several mechanisms, including increasing pelvic blood supply, inhibiting uterine contractions, stimulating the release of endorphins and serotonin, and altering the ability to receive and perceive pain signals [24,48,51,52].

Despite this, evidence supporting the use of non-pharmacological interventions is controversial [12,13]. Topical heat application and exercise were proven to significantly reduce menstrual pain, and their efficacy was comparable to that of NSAIDs [27,52]. The use of heating pads and regular physical exercise, either as an alternative or complementary therapy, should be encouraged because of their proven efficacy, uncommon harm, and low cost [13,30]. Nevertheless, there is insufficient evidence on the efficacy of dietary supplements (such as vitamins B, D, and E, or omega-3 fatty acids), acupuncture, yoga, massage, and herbal remedies in the management of PD [5,12,13,30,53].

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a non-invasive treatment modality that has been proven effective in reducing menstrual pain [13,54,55]. It is a small battery-operated portable device applied to the pelvic skin surface through adhesive electrodes that deliver electrical currents [54].

Its analgesic effect is mediated by two different mechanisms. The first mechanism involves increasing the sensory uterine pain threshold by transmitting a series of afferent electrical impulses via the large-diameter sensory fibers, thus resulting in reduced pain perception caused by uterine hypercontractility during menses, whereas the second mechanism involves inducing endorphin release by peripheral nerves resulting in pain attenuation [55-57]. TENS mainly consists of high-frequency (<50 Hz) or low-frequency TENS (2–5 Hz), with high-frequency TENS being the most commonly used since it has been demonstrated to be more efficient in reducing menstrual pain [56].

Several studies have confirmed the effectiveness and safety of TENS in PD, where it is recommended as an adjunct therapy or an alternative therapy for patients, who prefer to avoid using pharmacological agents [13,54,58-61]. TENS therapy is associated with minimal discomfort and adverse effects, in which, patients might experience muscle tightness or vibration, non-painful paresthesia over the site of pain dermatomes, headache, as well as slight skin redness after its use. An uncommon adverse effect reported includes increased menstrual blood flow [57,61]. Nonetheless, studies investigating TENS therapy for the management of PD exhibited significant variations in terms of study design, homogeneity of participants, TENS intensity, frequency of application, and duration of use. Therefore, further well-designed randomized controlled trials are required to study the long-term efficacy of TENS therapy and compare it with different pharmacological agents.

In rare instances, surgical interventions have been proposed for patients with severe dysmenorrhea, who do not respond to conventional treatment modalities. Surgical interventions include laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation (LUNA), presacral neurectomy (PSN), and hysterectomy [9,13,30]. Both LUNA and PSN involve the interruption of cervical sensory pain fibers through the transection of afferent nerve fibers either in the uterosacral ligaments or pelvis. However, since there is insufficient evidence to confirm the efficacy and safety of these interventions, they are unlikely to be recommended for treating PD [9,62]. In addition, hysterectomy is considered as the last resort in refractory severe cases, but should be avoided in adolescents and young females, and those wishing to conceive [63].

The response to empirical treatment for PD should be monitored. Both visual analogue and numeric rating scales are considered reliable, valid, and simple tools to assess the severity of dysmenorrhea at the initial presentation as well as treatment response stages [64]. Females who do not or inadequately experience clinical improvement after 6 months of empiric treatment should be assessed for adherence to therapies and regimen administration [12,13,30]. For patients whose symptoms persist despite adherence, further gynecological evaluation is recommended. This may include diagnostic uterine laparoscopy or magnetic resonance imaging to investigate the secondary causes of dysmenorrhea [12,13,30].

PD is a common disorder in females of reproductive age, that may go underdiagnosed or treated inadequately, owing to considerations ranging from secondary to cultural. It negatively affects the QOL, leading to decreased attendance at work and school, due to its wide variety of physical and psychological symptoms. Treatment of this condition is mainly based on pain relief either pharmacologically or by using alternative modalities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to professor Abdalla El-Lakany for facilitating the smooth conduction of this study.

Figure. 1.

Algorithm of the diagnosis and treatment of primary dysmenorrhea (PD). NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Table 1.

Summary of information related to primary dysmenorrhea

REFERENCES

1. Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update 2015;21:762-78.

2. Chen CX, Shieh C, Draucker CB, Carpenter JS. Reasons women do not seek health care for dysmenorrhea. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:e301-8.

4. Sharghi M, Mansurkhani SM, Larky DA, Kooti W, Niksefat M, Firoozbakht M, et al. An update and systematic review on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. JBRA Assist Reprod 2019;23:51-7.

6. Chen L, Tang L, Guo S, Kaminga AC, Xu H. Primary dysmenorrhea and self-care strategies among Chinese college girls: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026813.

7. Rafique N, Al-Sheikh MH. Prevalence of menstrual problems and their association with psychological stress in young female students studying health sciences. Saudi Med J 2018;39:67-73.

9. Parra-Fernandez ML, Onieva-Zafra MD, Abreu-Sanchez A, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Iglesias-Lopez MT, Fernandez-Martinez E. Management of primary dysmenorrhea among university students in the south of Spain and family influence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:5570.

10. Mendiratta V, Lentz GM. Primary and secondary dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. In: Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, editors. Comprehensive gynecology. 7th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier Inc.; 2017. p. 815-28.

11. Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, Hills R, Khan K. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:749-55.

12. Osayande AS, Mehulic S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician 2014;89:341-6.

13. Burnett M, Lemyre M. No. 345: primary dysmenorrhea consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2017;39:585-95.

14. Abreu-Sanchez A, Parra-Fernandez ML, Onieva-Zafra MD, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Fernandez-Martinez E. Type of dysmenorrhea, menstrual characteristics and symptoms in nursing students in southern Spain. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8:302.

15. Bernardi M, Lazzeri L, Perelli F, Reis FM, Petraglia F. Dysmenorrhea and related disorders. F1000Res 2017;6:1645.

16. Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev 2014;36:104-13.

17. Kuphal GJ. Dysmenorrhea. In: Rakel D, editor. Integrative medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier Inc.; 2018. p. 569-77.

18. Borgelt LM, Gunning KM. Disorders related to the menstrual cycle. In: Zeind CS, Carvalho MG, editors. Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs. 11th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Wolter Kluwer; 2018. p. 1005-27.

19. Unsal A, Ayranci U, Tozun M, Arslan G, Calik E. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and its effect on quality of life among a group of female university students. Ups J Med Sci 2010;115:138-45.

20. Abu Helwa HA, Mitaeb AA, Al-Hamshri S, Sweileh WM. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and predictors of its pain intensity among Palestinian female university students. BMC Womens Health 2018;18:18.

21. Wong CL. Health-related quality of life among Chinese adolescent girls with dysmenorrhoea. Reprod Health 2018;15:80.

22. Barcikowska Z, Rajkowska-Labon E, Grzybowska ME, Hansdorfer-Korzon R, Zorena K. Inflammatory markers in dysmenorrhea and therapeutic options. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1191.

23. Chan WY, Hill JC. Determination of menstrual prostaglandin levels in non-dysmenorrheic and dysmenorrheic subjects. Prostaglandins 1978;15:365-75.

24. Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:428-41.

25. Calis KA, Dang DK, Kalantaridou SN, Erogul M. Dysmenorrhea: practice essentials, background, pathophysiology [Internet]. New York (NY): Medscape; 2019 [cited 2021 Mar 8]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/253812-overview

26. Agarwal AK, Agarwal A. A study of dysmenorrhea during menstruation in adolescent girls. Indian J Community Med 2010;35:159-64.

27. Matthewman G, Lee A, Kaur JG, Daley AJ. Physical activity for primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:255.e1-255.e20.

28. Jones AV, Hockley J, Hyde C, Gorman D, Sredic-Rhodes A, Bilsland J, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of pain severity in dysmenorrhea identifies association at chromosome 1p13.2, near the nerve growth factor locus. Pain 2016;157:2571-81.

30. ACOG committee opinion no. 760: dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in the adolescent. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e249-58.

31. Brandt A, Agarwal N, Giri D, Yung Z, Didi M, Senniappan S. Hyperinsulinism hyperammonaemia (HI/HA) syndrome due to GLUD1 mutation: phenotypic variations ranging from late presentation to spontaneous resolution. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2020;33:675-9.

32. Katz JN, Smith SR, Collins JE, Solomon DH, Jordan JM, Hunter DJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis in older patients with multiple comorbidities. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:409-18.

33. Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke RO, Farquhar C, Proctor M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD001751.

34. Oladosu FA, Tu FF, Hellman KM. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug resistance in dysmenorrhea: epidemiology, causes, and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:390-400.

35. Lazzaroni M, Bianchi Porro G. Gastrointestinal side-effects of traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and new formulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20 Suppl 2:48-58.

36. Duggan KC, Walters MJ, Musee J, Harp JM, Kiefer JR, Oates JA, et al. Molecular basis for cyclooxygenase inhibition by the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug naproxen. J Biol Chem 2010;285:34950-9.

37. Harel Z. Dysmenorrhea in adolescents and young adults: an update on pharmacological treatments and management strategies. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012;13:2157-70.

39. Wong CL, Farquhar C, Roberts H, Proctor M. Oral contraceptive pill for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2009:CD002120.

40. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65:1-103.

41. Department of Reproductive Health. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 2021 Mar 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549158

42. Lindh I, Ellstrom AA, Milsom I. The effect of combined oral contraceptives and age on dysmenorrhoea: an epidemiological study. Hum Reprod 2012;27:676-82.

43. Maguire K, Westhoff C. The state of hormonal contraception today: established and emerging noncontraceptive health benefits. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205(4 Suppl):S4-8.

44. Lefebvre G, Pinsonneault O, Antao V, Black A, Burnett M, Feldman K, et al. Primary dysmenorrhea consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2005;27:1117-46.

45. Hinz B, Brune K. Paracetamol and cyclooxygenase inhibition: is there a cause for concern? Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:20-5.

46. Dawood MY, Khan-Dawood FS. Clinical efficacy and differential inhibition of menstrual fluid prostaglandin F2alpha in a randomized, double-blind, crossover treatment with placebo, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen in primary dysmenorrhea. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:35.e1-5.

47. Chen CX, Carpenter JS, LaPradd M, Ofner S, Fortenberry JD. Perceived ineffectiveness of pharmacological treatments for dysmenorrhea. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30:1334-43.

48. Armour M, Parry K, Al-Dabbas MA, Curry C, Holmes K, MacMillan F, et al. Self-care strategies and sources of knowledge on menstruation in 12,526 young women with dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14:e0220103.

49. Armour M, Smith CA, Steel KA, Macmillan F. The effectiveness of self-care and lifestyle interventions in primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2019;19:22.

50. Nie W, Xu P, Hao C, Chen Y, Yin Y, Wang L. Efficacy and safety of over-the-counter analgesics for primary dysmenorrhea: a network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e19881.

51. Daley AJ. Exercise and primary dysmenorrhoea: a comprehensive and critical review of the literature. Sports Med 2008;38:659-70.

52. Jo J, Lee SH. Heat therapy for primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis of its effects on pain relief and quality of life. Sci Rep 2018;8:16252.

53. Subasinghe AK, Happo L, Jayasinghe YL, Garland SM, Gorelik A, Wark JD. Prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhoea, and management options reported by young Australian women. Aust Fam Physician 2016;45:829-34.

54. Bai HY, Bai HY, Yang ZQ. Effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation therapy for the treatment of primary dysmenorrheal. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7959.

55. Jung JK, Byun JS, Choi JK. Basic understanding of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. J Oral Med Pain 2016;41:145-54.

56. Peng WW, Tang ZY, Zhang FR, Li H, Kong YZ, Iannetti GD, et al. Neurobiological mechanisms of TENS-induced analgesia. Neuroimage 2019;195:396-408.

57. Johnson M. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: mechanisms, clinical application and evidence. Rev Pain 2007;1:7-11.

58. Wang SF, Lee JP, Hwa HL. Effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on primary dysmenorrhea. Neuromodulation 2009;12:302-9.

59. Igwea SE, Tabansi-Ochuogu CS, Abaraogu UO. TENS and heat therapy for pain relief and quality of life improvement in individuals with primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2016;24:86-91.

60. Johnson MI, Paley CA, Howe TE, Sluka KA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for acute pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD006142.

61. Gibson W, Wand BM, Meads C, Catley MJ, O’Connell NE. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic pain: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;4:CD011890.

62. Proctor ML, Latthe PM, Farquhar CM, Khan KS, Johnson NP. Surgical interruption of pelvic nerve pathways for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD001896.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles in KJFM

-

Primary diagnosis and management of tremors.1998 December;19(12)

Primary evaluation and treatment of dizzy patients.2001 February;22(2)

The approach to diagnosis and treatment.2001 March;22(3)

Primary Aldosteronism: Current Concepts of Epidemic, Diagnosis, and Treatment.2005 November;26(11)