Association between Serum Cholesterol Level and Bone Mineral Density at Lumbar Spine and Femur Neck in Postmenopausal Korean Women

Article information

Abstract

Background

Blood lipid profiles have been suggested to be a risk factor for osteoporosis. However, the association between lipid profiles and bone mineral density (BMD) is still unclear. This study aimed to evaluate an association between blood lipid profiles and BMD through both a cross-sectional and a longitudinal study.

Methods

Study subjects were 958 postmenopausal Korean women who have repeatedly undertaken laboratory tests and BMD measurements at lumbar spine and femur neck with an interval of 7.1 years. The associations between lipid profiles and BMD were examined using Spearman correlation analysis with an adjustment for age, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, body mass index, and follow-up duration.

Results

Lumbar spine BMD was not associated with total cholesterol (TC), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HLD-C) regardless of when the measurement was performed. In an analysis using data measured at the beginning of the study, femur neck BMD was not associated with TC and LDL-C. However, femur neck BMD showed weak but significantly positive correlation with HDL-C (correlation coefficient, 0.077; 95% confidence interval, 0.005 to 0.149). When the analysis was repeated with data measured at the end of the follow-up, there was no significant correlation between femur neck BMD and any lipid profile. In addition, change in femur neck BMD during follow-up was not associated with the change in lipid profiles.

Conclusion

Although further study with a consideration of calcium intake and osteoporosis medication seems necessary, this study found no association between serum lipid profiles and BMD in postmenopausal Korean women.

INTRODUCTION

In accordance with the global trend of population aging, the average life span has greatly increased, thus, the elderly population is markedly increasing in Korea in recent years.1) It is well known that the increase in the number of elderly inevitably leads to an increase in the prevalence of chronic degenerative diseases in a population. Among aging related diseases, postmenopausal osteoporosis is an especially important health problem of elderly women which would result in a great increase in morbidity and mortality.2) In Korea, prevalence of osteoporosis is expected to increase continuously in the future, figuring from 27% in 2010 to 35% in 2020.3)

In order to prevent osteoporosis, it is essential to identify and manage the risk factors associated with a decrease in bone mineral density (BMD). Aging, lean physique, smoking, caffeine intake, insufficient intake of calcium and phosphorus, lack of exercise, family history of osteoporosis, and hyperthyroidism are the well-known key risk factors for osteoporosis.4,5) In addition, findings from studies in vitro and in vivo that oxydized low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) directly hinders differentiation of osteoblasts have suggested lipid profiles as a probable risk factor of osteoporosis.6,7) Being consistent with these results, an animal study found that fat components are piled up on bones or vessels around bone and induce reduced BMD in rats.8) Moreover, there have been studies reporting that osteoporosis is associated with atherosclerosis or calcification of the arteries,9-12) and that low BMD is significantly associated with greater cardiovascular mortality.13) Given that high LDL-C or low high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) are main risk factors for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease,14) it could be hypothesized that serum lipid profiles are significantly associated with BMD.

However, studies evaluating a direct association between serum lipid profiles and BMD have reported inconsistent findings. Some reported that higher LDL-C is associated with lower BMD,15-17) whereas others reported no association between the two.18-22) These conflicting findings call for further study. Moreover, most of the previous studies were conducted in Western populations and there were only few Asian studies evaluating the association between serum lipid profiles and BMD using cross-sectional design,17,23,24) which raises the necessity for additional studies in the Korean population who have a different distribution in lipid profiles and BMD.

In these regards, we evaluated the association between serum lipid profiles and BMD and the association between the changes in serum lipid profiles and BMD changes over several years in postmenopausal Korean women.

METHODS

1. Study Subjects

Study subjects were postmenopausal Korean women who have voluntarily undergone a routine health examination repeatedly with an interval of 6 to 8 years in a health promotion center of a tertiary care hospital located in Seoul after taking an initial health examination between January 2001 and December 2003. Among the initially identified 1,421 women, 463 women were excluded due to the following reasons: taking lipid-lowering drugs (220 women), hormone supplements (116 women), or both lipid-lowering drugs and hormone supplements (4 women) at final follow-up health examination; having higher free T4 level (>2.0 ng/dL, cut-off level which is known to affect bone metabolism)25) (26 women); information on smoking, drinking, and sports activity was missing (97 women). Thus, a total of 958 women were finally included.

2. Study Variables

Blood sample was drawn after 12-hour overnight fasting on the same day BMD was measured. Total cholesterol (TC), HDL-C, and LDL-C were assayed enzymatically in fresh serum in a laboratory. BMD (g/cm2) was measured at left femur neck and at lumbar spines (2nd, 3rd, and 4th) using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar Radiation Co., Madison, WI, USA). For analysis of lumbar spine, we used the averaged BMD values measured at 2nd, 3rd, and 4th level of lumbar spine. Height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured to the nearest 0.1 decimal point using a digital scale and stadiometer in light clothing and shoes taken off. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight divided by the height squared (kg/m2).

Information about health behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity) was assessed using a self-administered questionnaire. Study subjects were categorized into three groups by smoking habit (never smoker, ex-smoker, and current smoker), four groups by the level of physical activity ('do not exercise at all,' 'exercise less than once a week,' 'exercise 1-4 times a week,' and 'exercise more than 5 times a week'), and four groups by the levels of alcohol consumption ('never drinks,' 'drinks less than a bottle in a month,' 'drinks less than 2 bottles a month,' and 'drinks more than two bottles a month'). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Samsung Medical Center.

3. Statistical Analysis

Changes in the level of lipid profiles and BMD were calculated by subtracting the value at initial measurement from the value at final follow-up measurement. Because the distribution of lipid profiles and BMD measured at initial and final examination and the distribution of change in lipid profiles and BMD during follow-up did not follow normal distribution, we estimated the association between lipid profiles and BMD using Spearman correlation analysis with or without an adjustment for covariates such as age, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. At first, we evaluated the association between the lipid profiles and BMD measured at initial examination with a consideration of age and BMI measured at initial examination, and information on smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity measured at follow-up examination as covariates. Then, we evaluated the association between the lipid profiles and BMD measured at final follow-up examination with a consideration of age and BMI measured at follow-up examination, and information on smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity measured at follow-up examination as covariates. Finally, we evaluate the association between the changes in lipid profiles and the changes in BMD, with a consideration of age at initial examination, duration of follow-up, change in BMI during follow-up, information on smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity measured at follow-up examination as covariates. All the analyses were done using SAS ver. 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A two-sided test was done with the level of significance set at 'less than 0.05'.

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of Study Subjects

The mean (SD) interval between the time at initial and time at final examination was 7.1 (0.8) years. Mean (SD) age of study subjects at the initial examination was 58.6 (5.8) years (Table 1). During follow-up, mean (SD) height (cm) changed from 156.3 (4.9) to 156.0 (5.0) and mean BMI (kg/m2) shifted from 23.8 (2.7) to 23.8 (2.8). Total cholesterol (mg/L) level changed from 209.4 (33.3) to 204.3 (34.3), LDL-C (mg/L) from 140.3 (31.6) to 126.8 (30.2), HDL-C (mg/L) from 58.7 (14.1) to 57.0 (30.2), which was not a significant change. The BMD (g/cm2) at lumbar spine changed from 1.12 to 1.01 and the BMD at femur neck changed from 0.86 to 0.80, which was also not significant.

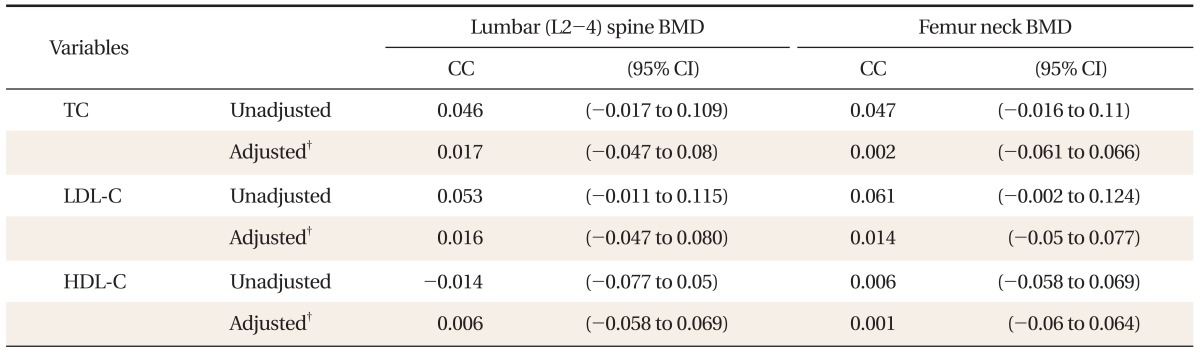

2. Cross-Sectional Association between Lipid Profiles and BMD

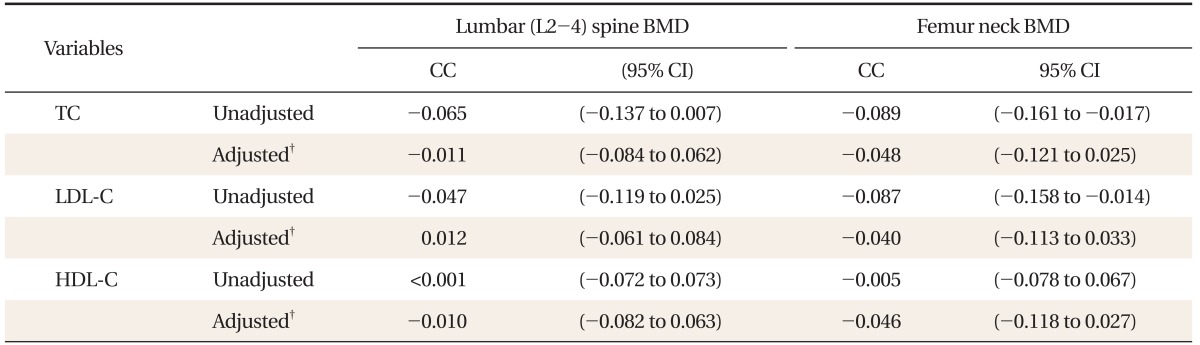

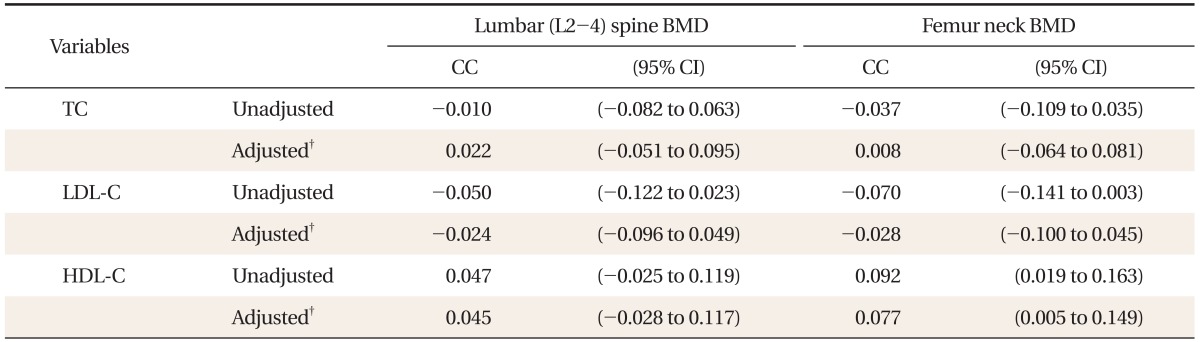

The lumbar spine BMD measured initially had no significant correlation with total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C. This finding did not change after the adjustment of age, smoking, drinking, exercise, and BMI (Table 2). The femur neck BMD measured initially had no significant correlation with total cholesterol and LDL-C, whereas it had a weak positive correlation with HDL-C (correlation coefficient, 0.092; 95% confidence interval, 0.019 to 0.163). The significant correlation between femur neck BMD and HDL-C did not change after the adjustment of covariates (partial correlation coefficient, 0.077; 95% confidence interval, 0.005 to 0.149). There was no significant correlation between the lipid profiles and BMDs (at lumbar spine and femur neck) measured at final follow-up examination regardless of the adjustment for covariates (Table 3).

Correlations* between lipid profile and bone mineral density measured at initial examination in postmenopausal Korean women.

3. Association between the Change in Lipid Profiles and Changes in BMDs over Follow-up Period

The change in BMD at lumbar spine had no significant correlation with the change in total cholesterol, LDL-C, and HDL-C level regardless of the adjustment for age, smoking, drinking, exercise, and BMI (Table 4). When covariates were not considered in analysis, change in femur neck BMD had weak but significant negative correlation with total cholesterol (correlation coefficient, -0.089; 95% confidence interval, -0.161 to 0.017) and LDL-C (correlation coefficient, -0.087; 95% confidence interval, -0.158 to -0.014). However, the correlation did not persist after the adjustment for covariates.

DISCUSSION

A unique feature of this study is that the association between the change in lipid profiles and the change in BMD over 7 years could be evaluated retrospectively using repeatedly measured data in large numbers of postmenopausal women. This longitudinal design allowed us to get better insight than a cross-sectional study regarding the causal association between those two variables.

In this study, LDL-C measured at initial examination as well as the change in LDL-C had no association with BMD at lumbar spine and femur neck. This finding is consistent with findings from previous epidemiological studies18-22) which reported that total cholesterol and LDL-C are not risk factors for low BMD.

Although HDL-C measured at initial examination was found to have a positive correlation with femur neck BMD in this study, we think this is not robust evidence supporting a true association between HDL-C and femur neck BMD because the analysis using the data measured at final examination or the data of changed value over time did not show any significant association.

One cross-sectional study conducted in the Japanese population reported a significant association of HDL-C with BMD at the lumbar spine and radius even after adjustment for other factors.17) However, this study was performed in a cross-sectional design that may have limitations for examining causal association. On the other hand, a study using the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data20) and a Korean study in pre- and postmenopausal women23) reported no significant association between HDL-C and BMD. Therefore, further investigation in studies of more advanced design seems necessary in order to clarify the causal association between HDL-C and BMD.

Several studies have suggested that serum lipid profiles and osteoporosis are closely related, which is inconsistent with the findings from our study. Some clinical trials came up with the conclusion that 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors preserved BMD and prevented osteoporosis,26,27) and osteoporosis treatment using bisphosphonate agents or postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy increased BMD with improved serum LDL-C and HDL-C level.28,29) However, the findings observed in these clinical trials only suggest that medications used in trials can affect both the serum lipid profiles and BMD and do not provide direct evidence that lipid profiles and BMD are causally associated. Furthermore, trials with postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy could not eliminate the confounding effect of estrogen on both lipid profiles and BMD. Our study has some strengths: we could evaluate the association between lipid profiles and BMD in postmenopausal women who were not under the influence of female sex hormone by excluding the women on hormone replacement treatment. We could also evaluate the influence of change in lipid profiles on BMD using longitudinal design. Therefore, we were able to evaluate the direct association between lipid profiles and BMD more accurately than the above mentioned clinical trials.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, study subjects are more likely to be in high socio-economic status, given that they are selected from those who undertook a routine health examination in the tertiary care hospital located in Seoul. Thus, it may be difficult to generalize findings from this study to women in different socioeconomic status. However, selection bias is less likely to play a significant role in our study because we evaluated an association between variables. Secondly, we could not take consideration of calcium intake and osteoporosis treatment that may have significant influence on BMD levels due to the lack of available data. Thirdly, time lag after menopause that may be related to the rate of decrease in BMD could not be taken into account due to lack of related data.30)

In conclusion, in this cross-sectional and follow-up study of postmenopausal Korean women, we found no significant association between serum lipid profiles and BMD. However, given the limitations of this study, this result should be carefully interpreted.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.