|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Volume 33(5); 2012 > Article |

Abstract

Background

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen are widely used in the treatment of tension headache. The objective of this study was to evaluate and compare the efficacy and safety of single doses of acetaminophen and NSAIDs using meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trial studies.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane, KMbase, KoreaMed, RiCH, National Assembly Library, Riss4u, and DBPIA for studies released through 27th July 2010. Two authors independently extracted the data. To assess the risk of bias, the Cochrane Collaborations risk of bias tool was used. Review Manager 5.0 was used for statistics.

Results

We identified 6 studies. The relative benefit of the NSAIDs group compared to the acetaminophen group for participants with at least 50% pain relief was 1.18 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99 to 1.39; I2 = 85%). We did subgroup analysis based on allocation concealment versus non-allocation concealment, and low-dose NSAIDs versus high-dose NSAIDs. The relative benefit of the low-dose NSAIDs subgroup to the acetaminophen group was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.91 to 1.06; I2 = 0%). However, the heterogeneity of other subgroup analysis was not settled. The relative risk for using rescue medication of the NSAIDs group compared to the acetaminophen group was 0.84 (95% CI, 0.64 to 1.12; I2 = 47%). The relative risk for adverse events was 1.31(95% CI, 0.96 to 1.80; I2 = 0%).

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis, there was no difference between low-dose NSAIDs and acetaminophen in the efficacy of the treatment for tension type headache. The results suggested that high-dose NSAIDs have more effect but also have more adverse events. The balance of benefit and harm needs to be considered when using high-dose NSAIDs for tension headache.

Tension type headache is the most common primary headache showing mild or moderate bilateral pains.1) It is a common disease with 78% of lifelong prevalence which occupies 40% of headache outpatients.2) Patients suffer from reduced social and economic capabilities such as reduced productivity at work and restricted activities in everyday life. Transient tension type headache may degrade quality of life and reckless drug use can convert it into a chronic tension type headache.

The purpose of drug treatment is to mitigate pains quickly without side effects. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen are the most common drugs used for the treatment of transient tension type headache.3) In some randomized clinical trials, it was judged that NSAIDs were more effective for pain control than acetaminophen. NSAIDs, however, were reported to accompany gastrointestinal side effects including peptic ulcer,4) increased the risk of myocardial infarction5) and heart failure,6) and the probability of side effects was proportional to dose. Additionally, there has not been consistency in the results of randomized clinical trials of these drugs on the pain control of tension type headache, and there have not been systematic reviews or meta-analyses comprehensively comparing the effects of those two drugs.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to systematically compare pain control effects and safety of NSAIDs and acetaminophen in the treatment of transient tension type headache patients through meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials.

Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials was performed in order to compare analgesic effects and safety of NSAIDs and acetaminophen in the treatment of transient tension type headache patients.

We included randomized clinical trials comparing the pain control effects of oral NSAIDs and oral acetaminophen on children or adult patients meeting the diagnosis standards of transient tension type headache by International Headache Society. We excluded participants if they suffered from chronic tension type headache or other headache patients such as migraine. Studies using oral NSAIDs and oral acetaminophen were included, but the studies using medication containing other ingredients such as caffeine were excluded.

The studies measured changes in the intensity of pain or the pain mitigation level according to time from 15 minutes to 24 hours after the administration of NSAIDs or acetaminiphen in visual analogue scale, categorical scale, or ordinal scale.

The final search was executed on July 27, 2010 by a professional librarian. There was no restriction on the language of publication.

The search was performed on MEDLINE (1966-July in 2010), EMBASE (1980-July in 2010), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) CINAHL (1982-July in 2010) using computer-based searches. For domestic materials, the search was performed on KoreaMed, KMbase, RiCH, National Assembly Library, Riss4u, and DBPIA. The search keywords used for MEDLINE and EMBASE were as follows.

"Tension-Type Headache"[MH] OR "Headache, Tension-Type"[TW] OR "Headaches, Tension-Type"[TW] OR "Tension Type Headache"[TW] OR "Tension-Type Headaches"[TW] OR "Idiopathic Headache"[TW] OR "Headache, Idiopathic"[TW] OR "Headaches, Idiopathic"[TW] OR "Idiopathic Headaches"[TW] OR "Stress Headache" OR "Headache, Stress" OR "Headaches, Stress" OR "Stress Headaches"[TW] OR "Tension Headache"[TW] OR "Headache, Tension"[TW] OR "Headaches, Tension"[TW] OR "Tension Headaches"[TW] OR "Psychogenic Headache"[TW] OR "Headache, Psychogenic"[TW] OR "Headaches, Psychogenic"[TW] OR "Psychogenic Headaches"[TW] OR "Tension-Vascular Headache"[TW] OR "Headache, Tension-Vascular"[TW] OR "Headaches, Tension-Vascular"[TW] OR "Tension Vascular Headache"[TW] OR "Tension-Vascular Headaches"[TW]

"anti-inflammatory agents, non-steroidal"[MH] OR NSAID*[TW] OR (non steroid* AND anti-inflammatory agent*[TW]) OR (non steroid* AND anti-inflammatory drug*[TW]) OR ("apazone"[MH] OR apazone[TW]) OR ("aspirin"[MH] OR aspirin[TW]) OR ("celecoxib"[NM] OR celecoxib[TW]) OR ("diclofenac"[MH] OR diclofenac[TW]) OR ("di f luni s a l "[MH] OR dif lunisal[TW]) OR ("etodolac"[MH] OR etodolac[TW]) OR ("fenoprofen"[MH] OR fenoprofen[TW]) OR ("flurbiprofen"[MH] OR flurbiprofen[TW]) OR ("ibuprofen"[MH] OR ibuprofen[TW]) OR ("indomethacin"[MH] OR indomethacin[TW]) OR ("ketoprofen"[MH] OR ketoprofen[TW]) OR ("ketorolac"[MH] OR ketorolac[TW]) OR meclofenamate OR ("meloxicam"[ NM] OR meloxicam[TW]) OR ("methyl salicylate"[NM] OR methylsalicylate[TW] OR methyl salicylate[TW]) OR ("nabumetone"[NM] OR nabumetone[TW]) OR ("naproxen"[MH] OR naproxen[TW]) OR ("nimesulide"[NM] OR nimesulide[TW]) OR ("oxaprozin"[NM] OR oxaprozin[TW]) OR ("phenylbutazone"[MH] OR phenylbutazone[TW]) OR ("piroxicam"[MH] OR piroxicam[TW]) OR salicylate[All Fields] OR ("sulindac"[MH] OR sulindac[TW]) OR ("tenoxicam"[NM] OR tenoxicam[TW]) OR ("tolmetin"[MH] OR tolmetin[TW])

"acetaminophen"[MeSH] OR 4 acetamidophenol[TW] OR 4 acetaminophenol[TW] OR 4 acetylaminophenol[TW] OR 4 hydroxyacetanilide[TW] OR 4' hydroxyacetanilide[TW] OR acenol[TW] OR acephen[TW] OR acetamino phenol[TW] OR acetaminophen[TW] OR acetaminophene[TW] OR acetaminophenol[TW] OR acetylaminophenol[TW] OR apamide[TW] OR apap[TW] OR apotel[TW] OR benuron[TW] OR calpol[TW] OR cp 500[TW] OR dafalgan[TW] OR doliprane[TW] OR duorol[TW] OR efferalgan[TW] OR fendon[TW] OR fibrinol[TW] OR gelocatil[TW] OR n acetyl 4 aminophenol[TW] OR n acetyl para aminophenol[TW] OR napap[TW] OR nebs[TW] OR nevral[TW] OR pamol[TW] OR panadol[TW] OR panadol soluble[TW] OR panasorb[TW] OR panodil[TW] OR paracetamole[TW] OR paralen[TW] OR paramax[TW] OR perfalgan[TW] OR phenaphen[TW] OR prompt[TW] OR sedes a[TW] OR tachipirina[TW] OR tempra[TW] OR tramil[TW] OR treuphadol[TW] OR tylenol[TW] OR valadol[TW]

(randomized controlled trial [PT] OR controlled clinical trial [PT] OR randomized controlled trials [MH] OR random allocation [MH] OR double-blind method [MH] OR single-blind method [MH] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [MH] OR ("clinical trial" [TW]) OR ((singl* [TW] OR doubl* [TW] OR trebl* [TW] OR tripl* [TW]) AND (mask* [TW] OR blind* [TW])) OR (placebos [MH] OR placebo* [TW] OR random* [TW] OR research design [MH:noexp])) NOT (animals [MH] NOT human [MH])

Two independent authors selected the studies satisfying the inclusion criteria from the results of the search. When there was disagreement, it was discussed between the authors. If agreement could not be made, the final selection was made with the coordination of a third writer.

To evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies, two independent authors evaluated the risk of bias of included studies using the Cochrane Collaborations risk of bias tool.7) It was judged that 'yes' in each item meant low risk of bias while 'no' meant high risk of bias. If a judgment could not be made, subjects were allowed to select 'unclear.' If disagreement occurred, consensus was sought after thorough discussions and repetitive reviews of the article.

Two independent authors abstracted research design, number and characteristics of subjects, medications and dose, follow-up periods, and outcomet variables. If disagreement occurred, agreement was later reached through discussions and repetitive reviews on the article.

To identify the number of patients who showed more than 50% pain relief, which is the threshold pain relief, mean total pain relief (TOTPAR) or summed pain intensity difference (SPID) measured from each group, was converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID,8) the ratio of the patients falling under 50% maxTOTPAR was calculated,9-11) and relative benefit (RB) of each group was identified and compared using the number of patients in each group. The formula was applied individually according to the linear regression analysis model.9-11) This method was proposed to make the meta-analysis easier by converting continuous variables to dichotomous variables when the pain scale was a continuous variable. When this method could not be used, the number of patients who fell in very good and excellent groups when they were measured by categorical global scale were classified as 50% maxTOTPAR.12)

RB or RR was proposed with 95% confidence interval (CI). To analyze the study results, Review Manager ver. 5.0 (RevMan; The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK)13) was used. The results were summarized into a table through forest plot and funnel plot was applied to check for publication bias. To identify heterogeneity, the I2 test was used. I2 statistics are the form of statistics quantifying inconsistency. I2 ranges from 0% to 100%. Here, values between 0% and 40% can be interpreted as unimportant heterogeneity, up to 60% as moderate heterogeneity and over 60% as considerable heterogeneity.14) When heterogeneity didn't exist, it was analyzed as a fixed effect model. When there was heterogeneity, the group was divided into subgroups with similar characteristics to investigate reasons of heterogeneity. If the heterogeneity could not be resolved, a random effect model was applied.

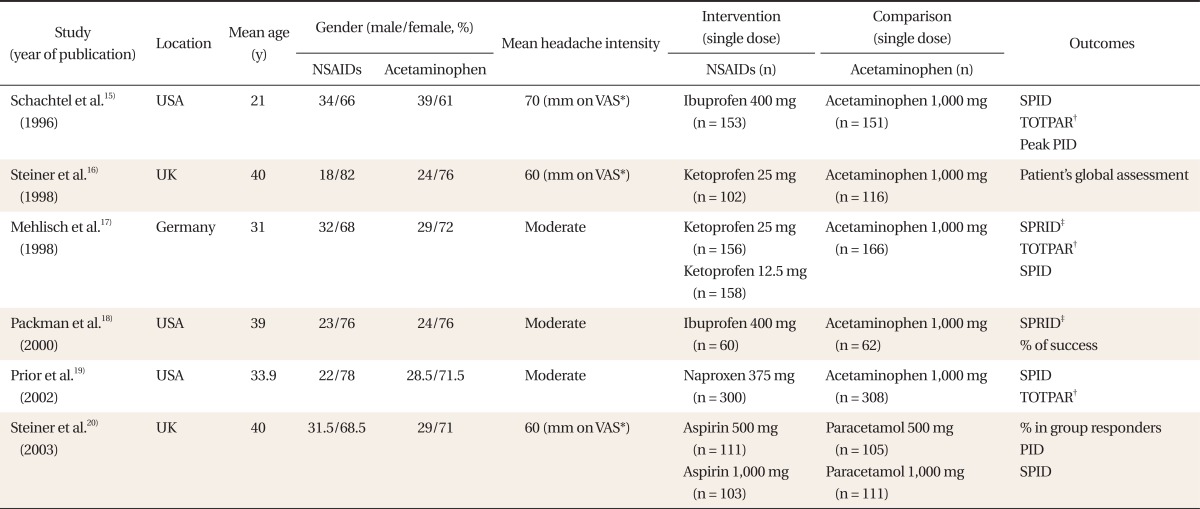

By electronic search, 18 records in PubMed, 15 records in Cochrane, and 24 records in EMBASE were searched, while there was no domestic literature. Investigating a total of 34 abstracts, 7 studies were selected. A study including migraine patients as subjects was excluded in the full-text review process, and 6 randomized controlled trials15-20) were selected and included in the analysis (Table 1).

A total of 2,162 participants (NSAIDs group 1,143, acetaminophen group 1,019) were included. The headache intensity of the cases included in the study was over moderate and the gender ratio of each group was similar (Table 1). Each study reported changes in the intensity of pains after the administration, whether rescue medications were used, and adverse effects.

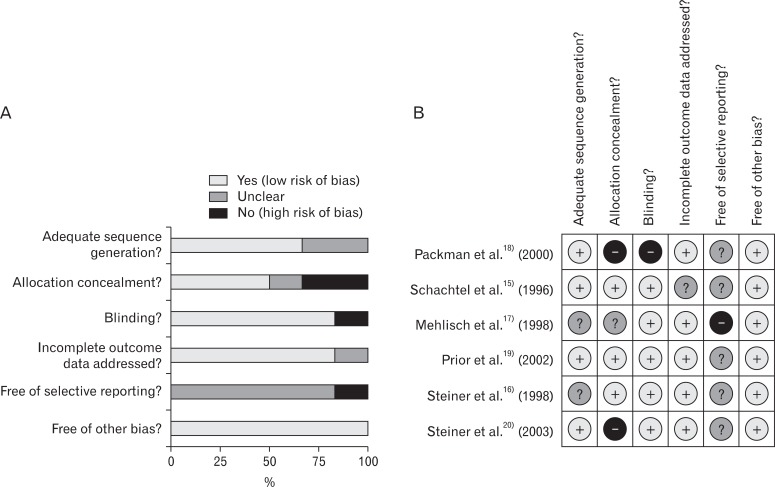

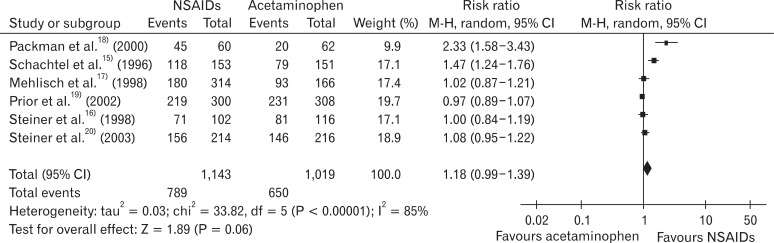

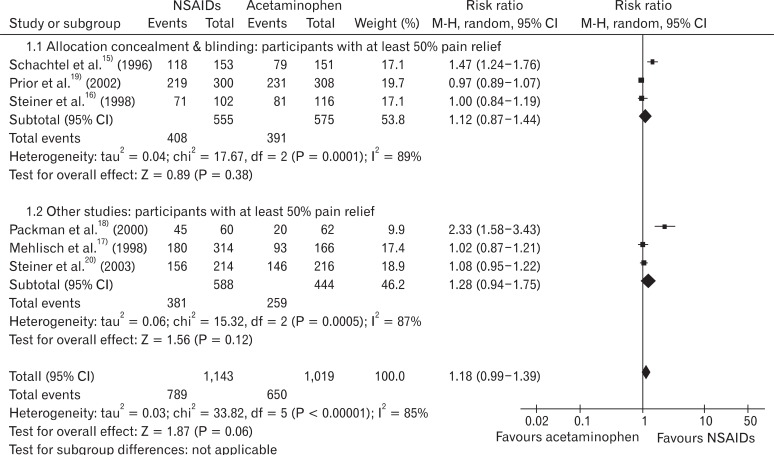

In the risk of bias evaluation using Cochran's bias risk evaluation tool,7) two studies were evaluated as 'uncertain' and the rest of the four studies were evaluated as 'yes' at the domain regarding the proper sequence generation. At the domain regarding allocation concealment (not to provide the participants with allocation information at the time of allocation), 50% of studies satisfied the criteria, while one study was found to be 'uncertain' and two studies 'no.' At the domain of selective reporting, 5 studies were 'uncertain' and one study was evaluated as 'no.' At the domain of blindness and incomplete data, 5 studies satisfied the criteria, and one study did not, respectively. Five studies, excluding Packman et al.18) which did not perform blindness and allocation concealment had relatively high quality (Figure 1). RB of the NSAIDs group to the acetaminophen group in 50% maxTOTPAR population was 1.18 (95% CI, 0.99 to 1.39), and I2 was 85% (Figure 2).

To identify the causes of heterogeneity among studies, subgroup analysis using proper allocation concealment or not, and groups using relatively low-dose NSAIDs such as ketoprofen 12.5 mg, naproxen 375 mg, and aspirin 500 mg, or high-dose NSAIDs such as ibuprofen 400 mg, ketoprofen 25 mg, and aspirin 1,000 mg. In the studies performing adequate allocation concealment,15,16,19) RB of the NSAIDs group to acetaminophen group was 1.12 (95% CI, 0.87 to 1.44), and I2 was 89%. In the studies that did not perform adequate allocation concealment,17,18,20) RB of NSAIDs group to acetaminophen group was 1.28 (95% CI, 0.94 to 1.75) and I2 was 87% (Figure 3).

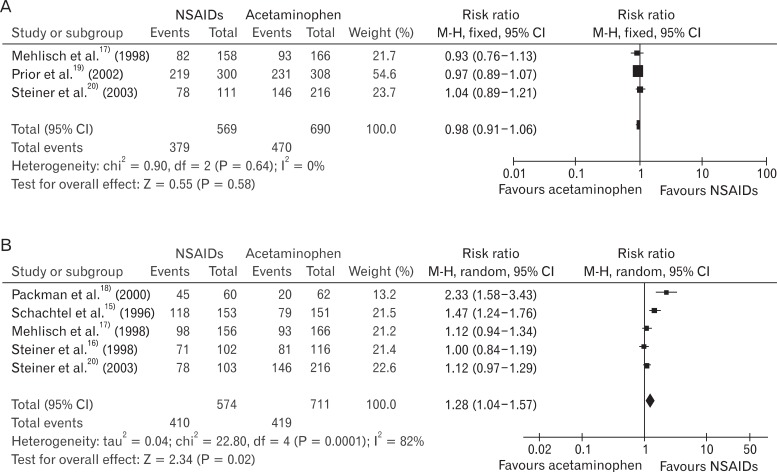

In the studies using relatively low-dose NSAIDs,17,19,20) RB was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.91 to 1.06) and I2 was 0%, which means heterogeneity was removed. In the studies using relatively high-dose NSAIDs,15-18,20) RB was 1.28 (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.57), and the heterogeneity was not removed (I2 = 82%) (Figure 4).

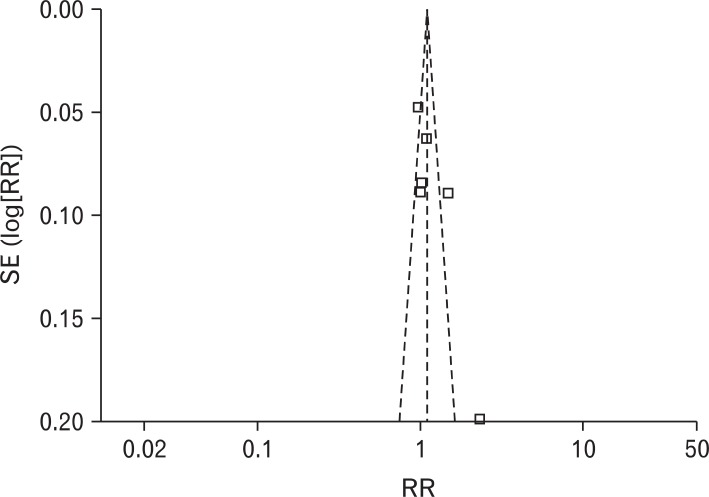

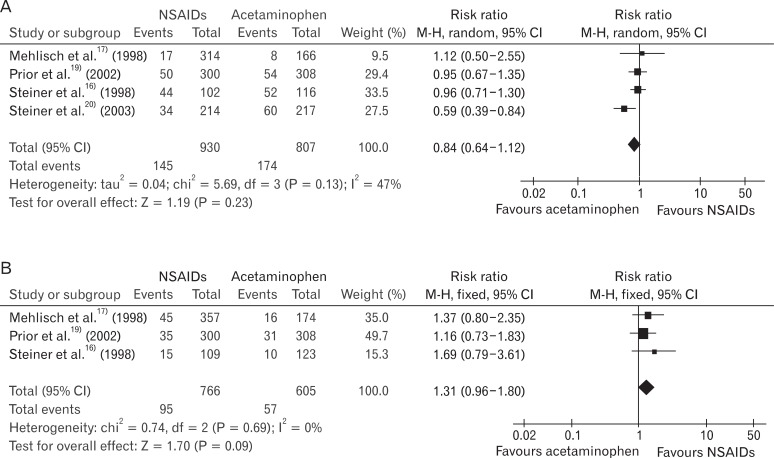

RR of using rescue medication was 0.84 (95% CI, 0.64 to 1.12), and the heterogeneity was not high (I2 = 47%). RR of the patients experiencing adverse effects was 1.31 (95% CI, 0.96 to 1.80), and there was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Figure 5). Obvious asymmetry was not observed in the funnel plot (Figure 6).

In this study, a total of 6 studies regarding analgesic effects of acetaminophen and NSAIDs in transient tension type headache were meta-analyzed. According to the results, there was no statistically significant difference in analgesic effect between acetaminophen and NSAIDs, and they showed a high degree of heterogeneity. To investigate the cause of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was performed. When subgroup analysis was performed according to allocation concealment, heterogeneity was not settled. When excluding the patients using acetaminophen 500 mg, it was found that RB was insignificant as 1.17 (95% CI, 0.98 to 1.39) and heterogeneity was not settled (I2 = 85%). In cases administrating relatively high-dose NSAIDs, RB was significant as 1.28 but heterogeneity was not settled.

Accordingly, it is difficult to make a conclusion about which medication is more effective to pain alleviation in transient tension type headache patients between NSAIDs and acetaminophen. When relatively low dose NSAIDs were used, heterogeneity was removed, which means low dose NSAIDs did not have bigger pain alleviation effects than acetaminophen. The use of rescue medication did not show a significant difference in the two medications and showed moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 47%).

Overall, 5 studies reported adverse effects. Out of them, 2 studies reported that there were no patients experiencing adverse effects. The rest of them except one study which did not mention about adverse effects reported mild side effects. Digestive systemrelated adverse effects were most frequent. More adverse effects were reported in the NSAIDs group but there was no statistical significance.

Out of six studies included in this meta-analysis, 4 studies reported that NSAIDs were more effective than acetaminophen in pain alleviation. This meta-analysis, however, judged that it was difficult to make a clear conclusion as to which medication between NSAIDs and acetaminophen was more effective in pain alleviation of transient tension type headache patients. When relatively low-dose NSAIDs were used, heterogeneity was removed, which means low-dose NSAIDs did not have greater pain alleviation effects than acetaminophen. In other words, it is highly probable that low-dose NSAIDs may not be more effective than acetaminophen in pain alleviation. It is possible that high-dose NSAIDs are more effective, but high-dose NSAIDs may increase the risk of side effects,4) such as in the gastro-intestinal tract.

In conclusion, in this meta-analysis, there was no difference between low-dose NSAIDs and acetaminophen in the efficacy of the treatment for tension type headache. The results suggest that high-dose NSAIDs have more effect but also have more adverse events. The balance of benefit and harm needs to be considered when using high-dose NSAIDs for tension headache.

References

2. Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olesen J. Epidemiology of headache in a general population: a prevalence study. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:1147-1157. PMID: 1941010.

3. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Diagnosis and management of headache in adults: a national clinical guideline [Internet]. 2008. [cited 2012 July 12]. Edinburgh: SIGN; Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/107/index.html

4. Hernandez-Diaz S, Rodriguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: an overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2093-2099. PMID: 10904451.

5. Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, Schramm TK, Hansen ML, Fosbol EL, et al. Increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:141-149. PMID: 19171810.

6. Fosbol EL, Gislason GH, Jacobsen S, Folke F, Hansen ML, Schramm TK, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and death associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) among healthy individuals: a nationwide cohort study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;85:190-197. PMID: 18987620.

7. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. . Chapter 8, Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [Internet]. Version 5.0.0. 2008. [cited 2012 July 12]. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [updated 2008 Feb]

8. Cooper SA. In: Max MB, Portenoy RK, Laska EM, editors. Single-dose analgesic studies: the upside and downside of assay sensitivity. The design of analgesic clinical trials. Advances in pain research and therapy. 1991. vol. 18. New York: Raven Press; p. 117-124.

9. Moore A, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics. Pain 1996;66:229-237. PMID: 8880845.

10. Moore A, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: verification from independent data. Pain 1997;69:127-130. PMID: 9060022.

11. Moore A, Moore O, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: use of pain intensity and visual analogue scales. Pain 1997;69:311-315. PMID: 9085306.

12. Collins SL, Edwards J, Moore RA, Smith LA, McQuay HJ. Seeking a simple measure of analgesia for mega-trials: is a single global assessment good enough? Pain 2001;91:189-194. PMID: 11240091.

13. The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.0.. 2008. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration.

14. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. . Chapter 9, Analysing data and undertaking metaanalysis. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [Internet]. Version 5.0.0. 2008. [cited 2012 July 12]. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [updated 2008 Feb]

15. Schachtel BP, Furey SA, Thoden WR. Nonprescription ibuprofen and acetaminophen in the treatment of tension-type headache. J Clin Pharmacol 1996;36:1120-1125. PMID: 9013368.

16. Steiner TJ, Lange R. Ketoprofen (25 mg) in the symptomatic treatment of episodic tension-type headache: double-blind placebo-controlled comparison with acetaminophen (1000 mg). Cephalalgia 1998;18:38-43. PMID: 9601623.

17. Mehlisch DR, Weaver M, Fladung B. Ketoprofen, acetaminophen, and placebo in the treatment of tension headache. Headache 1998;38:579-589. PMID: 11398300.

18. Packman B, Packman E, Doyle G, Cooper S, Ashraf E, Koronkiewicz K, et al. Solubilized ibuprofen: evaluation of onset, relief, and safety of a novel formulation in the treatment of episodic tension-type headache. Headache 2000;40:561-567. PMID: 10940094.

19. Prior MJ, Cooper KM, May LG, Bowen DL. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen and naproxen in the treatment of tension-type headache. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cephalalgia 2002;22:740-748. PMID: 12421160.

20. Steiner TJ, Lange R, Voelker M. Aspirin in episodic tension-type headache: placebo-controlled dose-ranging comparison with paracetamol. Cephalalgia 2003;23:59-66. PMID: 12534583.

Figure 2

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) vs. acetaminophen: participants with at least 50% pain relief. CI: confidence interval.

Figure 3

Subgroup analysis: participants with at least 50% pain relief (allocation concealment & blinding vs. other studies). CI: confidence interval.

Figure 4

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) vs. acetaminophen: participants with at least 50% pain relief (low-dose NSAIDs and high-dose NSAIDs). (A) Low dose NSAIDs vs. acetaminophen: participants with at least 50% pain. (B) High dose NSAIDs vs. acetaminophen: participants with at least 50% pain.

Figure 5

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) vs. acetaminophen: rescue medication and adverse events. (A) NSAIDs vs. acetaminophen: participants using rescue medication. (B) NSAIDs vs. acetaminophen: participants using rescue medication.

Table 1

Characteristics of included studies.

NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, VAS: visual analogue scale, SPID: sum of pain intensity differences, PID: pain intensity difference.

*100-mm VAS. †The time-interval weighted sum of the pain relief scores. ‡Sum of pain relief intensity differences calculated by summing the product of the pain relief intensity difference (PRID, the sum of pain intensity and pain relief scores).

- TOOLS