Epiglottic Cyst Incidentally Discovered During Screening Endoscopy: A Case Report and Review of Literature

Article information

Abstract

From the endoscopists' point of view, although the main focus of upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination is the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (usually bulb and 2nd portion including ampulla of Vater), the portions of the upper airway may also be observed during insertion and withdrawal of the endoscope, such as pharynx and larynx. Thus, a variety of pathologic lesions of the upper airway can be encountered during upper endoscopy. Among these lesions, an epiglottic cyst is relatively uncommon. The cyst has no malignant potential and mostly remains asymptomatic in adults. However, if large enough, epiglottic cysts can compromise the airway and can be potentially life-threatening when an emergency endotracheal intubation is needed. Thus, patients may benefit from early detection and treatment of these relatively asymptomatic lesions. In this report, we present a case of epiglottic cyst in an asymptomatic adult incidentally found by family physician during screening endoscopy, which was successfully removed without complication, using a laryngoscopic carbon dioxide laser.

INTRODUCTION

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is a common and established procedure for the diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment of a variety of upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract disorders including gastric neoplasm.1,2) The incidence of stomach cancer is high in East Asian countries including China and South Korea,3,4) compared to Western countries in Europe and North America. In South Korea, stomach cancer is the second most common cancer and third most common cause of cancer death.5) Additionally, the cost of EGD is relatively low at approximately $60 US per endoscopic examination. Thus, screening upper GI endoscopy is widely performed in this East Asian country.5,6,7) However, the number of gastroenterologic specialists is not sufficient to meet the growing demand. Consequently, family physicians have contributed to meeting this demand by performing EGD.8,9,10)

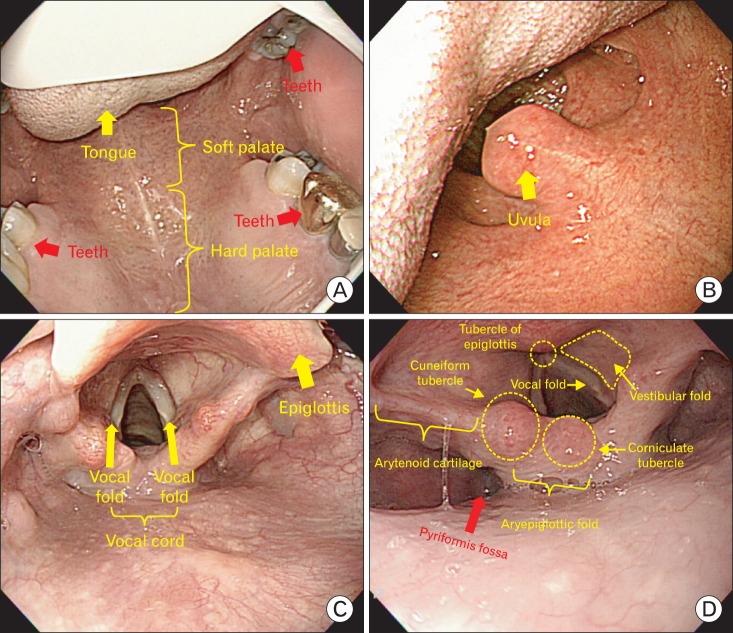

The primary focus of EGD is the examination of the esophagus, stomach, and proximal duodenum (usually till 2nd portion).11) However, oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx including the epiglottis may also be observed during the insertion and withdrawal of the endoscope (Figure 1). Therefore, diverse non-upper GI lesions may be encountered during EGD.12) In this report, we present a 55 year-old-patient with an asymptomatic epiglottic cyst incidentally found during screening endoscopy, along with a review of the relevant literature.

CASE REPORT

An asymptomatic 55-year-old woman with a family history of gastric cancer visited at the Department of Family Practice and Community Health, Ajou University Hospital for routine medical check-up including a screening EGD for upper GI cancer. She had hypertension that was controlled with medication, and had no other medical illness or surgical history. The patient did not smoke tobacco nor drink alcohol.

On general examination, the patient was healthy-looking in appearance, but obese (height, 160.3 cm; weight, 71.1 kg, waist circumference 101.2 cm; body mass index, 27.7 kg/m2). The patient's vital signs showed a blood pressure of 115/70 mm Hg, a regular heart rate of 70 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 18 rates/min, and a body temperature of 36.7℃. Other aspects of the physical examination including abdomen were unremarkable as well. All laboratory tests such as complete blood cell counts, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, protein, albumin, electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, lipid panel (total cholesterol, triglyceride, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and low density lipoprotein cholesterol), fasting glucose, urine analysis, and stool examination were all within normal limits. Radiologic evaluations including chest X-ray, abdomen supine/erect X-ray, and abdominal ultrasonography were also without significant findings.

Two years previous to this EGD, the patient had undergone screening EGD with sedation, which was without significant findings or complications. At this time, she wanted EGD with sedation in order to avoid discomfort and anxiety about the procedure. Thus, we decided to perform EGD under conscious sedation, and written informed consent was obtained from the patient. After fasting for 12 hours (nothing by mouth after dinner the day before the EGD), the EGD was commenced the next morning. First, 10% lidocaine (Xylocaine spray; AstraZeneca Korea Pharmaceutical Co., Seoul, Korea) was sprayed as local pharyngolaryngeal anesthesia. Then, the patient was placed in left lateral decubitus position. The EGD was performed under conscious sedation with combinations of intravenous midazolam (Dormicum; Roche Korea Pharmaceutical Co., Seoul, Korea) and propofol (Pofol; Jeil Pharmaceutical Co., Seoul, Korea). In addition, an antispasmodic agent, cimetropium bromide (Algiron; Green-Cross Pharmaceutical Co., Yongin, Korea), was given intravenously immediately before the procedure to minimize upper GI movements, which can interfere with detailed and complete inspection. The endoscopist performed the procedure on the patient with an Olympus GIF-H260 video endoscope (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). During the procedure, blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation were monitored.

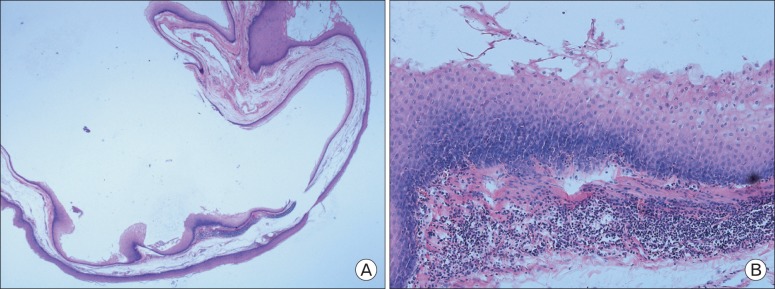

When the endoscope was intubated into the oral cavity (Figure 2A-C), an approximately 15 × 30 mm sized globular yellowish cystic mass with smooth surface and visible vessels was seen arising from the right side of epiglottis (Figure 2D, E). This lesion had not been present during the index examination 2 years prior. Fortunately, the lesion was not obstructing the airway. Both the left and right vocal cords were intact, well-mobile, and free of adhesions (Figure 2F, G). Also, the lesion did not interrupt the advance of the endoscope, which was inserted through piriformis fossa (Figure 2H) into the esophagus (Figure 2I). The remainder of the examination was without abnormal findings except for mild chronic superficial gastritis in the antrum.

(A-I) In our case, endoscopic findings of serial series during insertion of the endoscope. (A) Arrow: tongue, (C) arrow: uvula, (D) arrow: the cystic-like mass in right side of lingual surface of epiglottis discovered during insertion of endoscope, (E) arrow: epiglottis, dotted line: epiglottic cystic-like mass, (G) arrow: each vocal cords (i.e., vocal fold), (H) arrow: piriformis fossa (i.e., the direction of insertion through oral cavity into esophagus), (I) upper esophagus.

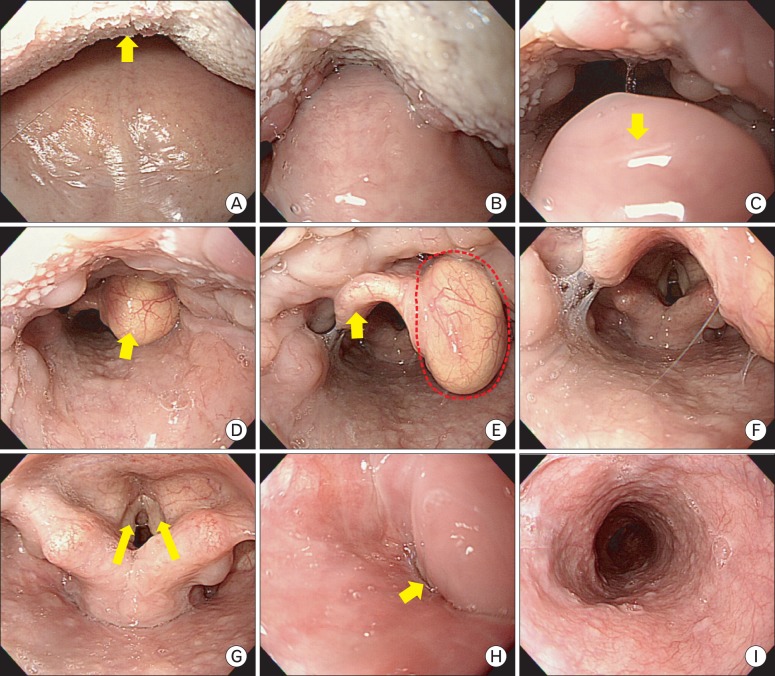

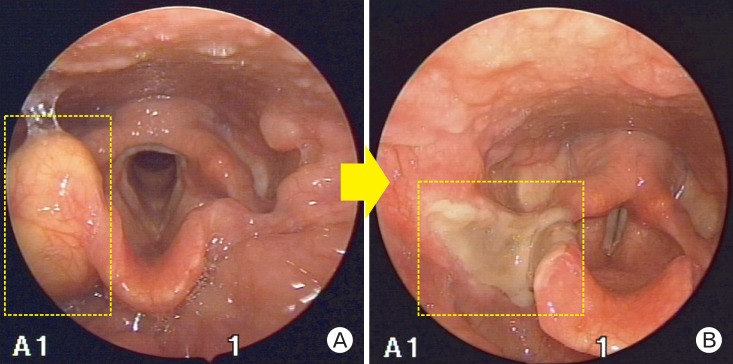

Although the patient was asymptomatic, the patient was referred to the otolaryngology department because of the accelerated growth of the lesion to a relatively large size within a 2 year period and the possibility of airway obstruction and difficulty in intubation in future emergency situations. The cystic-like mass was resected by carbon dioxide (CO2) laser under operating micro-laryngoscope (Figure 3) and sent for histopathology, after which the lesion was confirmed to be a benign epiglottic cyst. On hematoxylin and eosin stain, the cyst was lined by columnar to cuboidal epithelium without lymphoid infiltration (Figure 4A, B). The patient tolerated the procedure well, and the post-operative course was uneventful. She was discharged the day after her admission in stable condition. No recurrence was noted at the follow-up outpatient clinic visit.

Laryngoscopic findings during the resection of cystic-like mass in right lingual surface of epiglottis. (A) Before treatment by carbon dioxide laser (in dotted line). (B) After treatment by carbon dioxide laser (in dotted line).

DISCUSSION

Laryngeal cyst is a rare entity and constitutes only 4.3% to 6% of all benign laryngeal tumors.13) In 1852, Verneuil first described the presence of a laryngeal cyst in a post-mortem of an infant.14) Also, in 1864, Durham15) first reported a case of epiglottic cyst in an 11-year-old boy, which was successfully treated by surgical incision. Since then, a variety of cases have been reported, but the laryngeal cysts, including epiglottic variants, still present a relatively rare occurrence.

The larynx extends vertically from the tip of the epiglottis to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage, i.e., the entrance of the trachea. The function of the larynx is involved in breathing, sound production (phonation), and protection of the trachea against food aspiration. The epiglottis is one of nine cartilaginous structures that make up the larynx; the laryngeal skeleton consist of nine cartilage structures, three single (epiglottic, thyroid, cricoid) and three paired (arytenoid, corniculate, cuneiform) (Figure 1). Epiglottic cysts arise in the region of epiglottis, a thin valve-like structure made of cartilage that is located behind the base of tongue. The lingual surface of the epiglottis is the most common location for these lesions. Henderson et al. demonstrated that 52% of the laryngeal cysts originated from the lingual aspect of the epiglottis in their study.16) In our case, the lesions were discovered on the lingual surface of the epiglottis as well.

Epiglottic cyst seems to be more prevalent in the 6th decade of life, which was the case in this patient, although they can affect and have been reported in all ages.13) Because the diameter of the respiratory tract is smaller in infants and children, an epiglottic cyst may easily obstruct the airway in this age group, and sufficiently large cysts may present as stridor, cyanosis with feeding, respiratory difficulty, and have the potential to be life-threatening. However, most adult epiglottic cysts are benign and asymptomatic.17) Therefore, these anomalies are sometimes discovered unintentionally during routine otolaryngological examination, induction of general anesthesia, and upper GI endoscopy, because this area is the passage to going into the esophagus during endoscopic examination. In our case, the lesion was incidentally found during screening endoscopy for gastric cancer, and the patient had been asymptomatic and unaware of the lesion. However, in accordance with the size and extension into the airway, there were symptoms associated these lesions such as foreign body sensation in the throat, hoarseness, cough, stridor, and dysphagia. Additionally, epiglottic cyst may have a future risk of airway obstruction.17,18) For example, during induction of anesthesia, asymptomatic and undiagnosed epiglottic cyst may cause the development of respiratory failure when muscular relaxation may drive cysts into the larynx causing partial or complete obstruction, which may lead to unanticipated difficulty in ventilation or intubation or both.19) Thus, lesions can be potentially life-threatening and may require tracheostomy in emergency situations. Another potential complication of lesions is secondary infection of the cyst. This may progress to the epiglottitis and epiglottic abscess, which can also be a cause of airway obstruction and respiratory arrest.20,21,22) Thus, early intervention may be prudent for incidentally found epiglottic cyst in adults, though they may be symptomless and small in size. Treatment options include endoscopic excision, marsupialization, unroofing, and lateral pharyngotomy.23,24,25) Recently, CO2 laser has been successfully applied in nearly all cases due to superior coagulation of the laser and shorter time to recovery.16,22,26) Simple aspiration is no longer recommended due to high recurrence rates,27) but can be used for volume reduction prior to surgical or CO2 laser resection. In our case, the epiglottic cyst of our patient was completely removed using CO2 laser under operating micro-laryngoscope without complications. Local recurrence of epiglottic cysts can be minimized by complete removal of the cyst wall. In certain cases, prophylatic antibiotics may occasionally be helpful after treatment to avoid acute epiglottitis.28)

There are a variety of pathohistological classifications of laryngeal cysts including epiglottic cysts. In 1922, Myerson classified these cysts into retention, embryonic, vascular, and traumatic types.29) However, this classification was complex and impractical. In 1970, DeSanto et al.30) divided these anomalies into two types: 1) Ductal-type and 2) Saccular-type. The ductal-type was considered to be caused by the obstruction of excretory duct of submucosal glands; whereas the saccular-type was considered to have developed as a result of excessive extension of the saccule of the ventricular fold in the larynx. In a histologic study published in 1984, Newman et al.31) categorized the lesions according into three types: 1) Epithelial-type, 2) Tonsillar-type, and 3) Oncocytic-type. In our case, the lesion was of ductal-type by DeSanto classification and epithelial type by Newman's histologic classification.

Since its first introduction in early 19th, EGD has been accepted as the best tool for the diagnosis and follow-up of upper GI disorders, including screening of gastric neoplasms. Therefore, the demand for EGD continues to grow worldwide, especially in Asian countries where the incidence of gastric cancer is comparatively high. During EGD, the endoscopists' main focus of examination is the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum bulb and 2nd portion. However, incidental upper airway lesions can be identified in the pharynx and larynx, including those of the epiglottis and vocal cords, during the insertion and withdrawal of the endoscope into and from the esophagus.

These lesions of the pharynx and larynx may be of malignant neoplasms or pathologic lesions with malignant potential. Additionally, even though such a lesion is benign, it may represent a future risk of complications, as deemed for the patient in our case. Therefore, this area should also be examined thoroughly during insertion as well as withdrawal of endoscope. Also, if a lesion is incidentally discovered in the area, proper and careful judgment by the endoscopist (follow-up versus further work-up versus immediate intervention including referral to other department) with regard to the patient is required.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.