Changes in the Degree of Patient Expectations for Patient-Centered Care in a Primary Care Setting

Article information

Abstract

Background

To date, the medical environment has been undergoing continual changes. It is therefore imperative that clinicians recognize the changing trends in the degree of patient expectations for patient-centered care. We conducted this study to examine changes in the degree of patient expectations for patient-centered care and the related socio-demographic factors in a primary care setting over a 5-year period.

Methods

We evaluated patients' attitudes toward patient-centered care using the Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale, which provides 'sharing' and 'caring' scores. The study included 359 and 468 patients in phase I (March-July, 2005) and II (March-July, 2010). We also examined the relationship of their changes to their socio-demographic factors.

Results

In phase II, as compared with phase I, the 'sharing' score was higher (3.67 ± 0.68 vs. 3.82 ± 0.44; P < 0.001) and 'caring' one was lower (4.01 ± 0.57 vs. 3.67 ± 0.58; P = 0.001). Further, 'sharing' and 'caring' scores were associated with age, monthly income, education level, marital status, and the functional health status of patients.

Conclusion

These results would be of help for providing patient-centered care for patients because it makes clinicians are aware of the degree to which patients' expect it.

INTRODUCTION

Patient-centered care, in contrast to doctor-centered, refers to understanding a patient as a unique human-being,1) trying to grasp the thoughts and feelings of the patient, to communicate kindly with the patient (a concept of 'caring'),2) and establishing a relationship of sharing medical information and power-sharing between doctors and patients (a concept of 'sharing').3)

As compared to the traditional doctor-patient relationship, patient-centered care is an evidence-based concept for improving clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.4,5,6) Due to its important benefits for patients, more emphasis has been placed on it in current practice.7,8,9) However, its implementation in practice is limited because the traditional model of the doctor-patient relationship, such as the authoritative doctor and the passive, receptive patient, still dominates doctor-patient encounters. Indeed, although patients are a central component of the healthcare system, the patients' perspectives or preferences about patient-centered care have not been considered by healthcare providers.10) Thus, understanding the patients' expectations regarding patient-centered care would be the first step in implementing patient-centeredness in clinical practice.

Changes in the healthcare environment deserve special attention due to the following reasons: (1) The availability of medical information and knowledge has been increasing due to the internet or other media.11) Owing to this easier access to medical information and knowledge, patients are increasingly interested in healthcare issues than before. Moreover, they now have more access to alternative opinions about their diagnosis and treatment.12) These changes may affect patients' perspectives about the doctor-patient relationship. (2) The number of patients who consider themselves as a medical consumer, who claim the right to appropriate medical services based on the recognition that they deserve special treatment, is increasing.13,14) Moreover, there is a tendency that medical consumers are spending more of their own income on health care, with an estimated increase of 2.5% to 3.5% per year with increasing age.11)

As described above, the medical environment has been undergoing continual changes. It is therefore imperative that clinicians recognize the changing trends in the degree of patient expectations for patient-centered care based on the sharing and caring concept, which is essential for effectively implementing patient-centered care in a clinical setting. However, there is a paucity of clinical research about the change in the patients' attitudes toward patient-centered care in a primary care setting. Moreover, there is also a possibility that considering socio-demographic factors, specific approaches for a patient population might help to implement patient-centered care in a clinical setting. Thus, it would be meaningful to examine whether changes in the degree of patient expectations for patient-centered care, if any, are associated with specific demographic factors. Given the above background, we conducted this study to examine the changes in the degree of patient expectations for patient-centered care and the related socio-demographic factors in a primary care setting over a 5-year period.

METHODS

1. Subjects and Research Design

The current study was conducted in two phases (phase I: March-July, 2005 and phase II: March-July, 2010). In each phase, we performed a self-report questionnaire survey. In phase I, 400 patients from ten different family medicine clinics at Seoul or Gyeonggi province in South Korea were given questionnaires. We excluded the patients who were aged 20 years or younger, and those who were deemed to have an inability to complete a self-report questionnaire because of health problems such as visual or mental problems. We collected back 384 questionnaires from the patients who participated in the phase I study. Further, we excluded the patients who did not fully respond to the Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale (PPOS) items from the current analysis. Thus, 359 patients participated in the phase I study. The phase II study was conducted in the same way as phase I. The clinics from which the participants were recruited and exclusion criteria were the same as those employed in phase I. We collected 492 out of the 500 questionnaires distributed to the patients who participated in the phase II study. Excluding the patients who did not fully respond to the PPOS items, we analyzed 468 questionnaires in phase II.

We obtained a written informed consent from all the patients. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the Catholic University of Korea (IRB approval number: KC10EISI0056).

2. Instruments

In phases I and II, the patients were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire based on the PPOS. The PPOS, which was used to measure the degree of patients' expectations for patient-centered care in the current study, was first developed by Krupat et al.15,16) in an effort to measure the attitudes of either patients or clinicians towards aspects of the physician-patient relationship (e.g., patient- or doctor-centeredness). Translated into Korean by Sohn et al.,17) and used by several Korean studies,18,19,20) the PPOS comprises 18 items on a 6-point Likert format. It includes two nine-item subscales measuring 'sharing' and 'caring' scores, respectively. These subscales are based on the degree of belief that patients should be well informed by doctors and this should be a decision-making process between the two parties, and that patients should be well taken care of, respectively. The mean PPOS score is the average value for all 18 items. The 'sharing' and 'caring' scores are calculated by averaging values for the nine items in the subscale. Values closer to 6 are indicative of a higher degree of patient-centered responses. Conversely, values closer to 1 are indicative of a higher degree of doctor-centered responses. The test-retest reliability of the tool was r = 0.75 and the Cronbach's alpha for internal consistency was 0.63. Patients were also asked to report their socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, marital status, education level, monthly income, chronic diseases, and functional health status.

3. Statistical Analysis

We used the chi-square test to compare phase I and II in terms of the demographic characteristics and changes in the degree of patient agreement on each item. We analyzed the differences in the mean PPOS scores and 'sharing' and 'caring' scores between phase I and II, using analysis of covariance for covariates such as gender, age, marital status, education level, monthly income, functional health status, and chronic diseases. We also used a two-way nested analysis of variance to analyze the differences in the mean PPOS scores and 'sharing' and 'caring' scores in terms of the demographic variables within year. The statistical analysis was done using the PASW ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

RESULTS

1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Patients

As shown in Table 1, there were differences in the age, marital status, education level, monthly income, and functional health status of the participants in phase I and II. However, there were no differences in gender, and a history of chronic diseases.

2. Changes in Mean PPOS Scores and 'Sharing' and 'Caring' Scores over a 5-Year Period after Adjusting for Socio-Demographic Factors

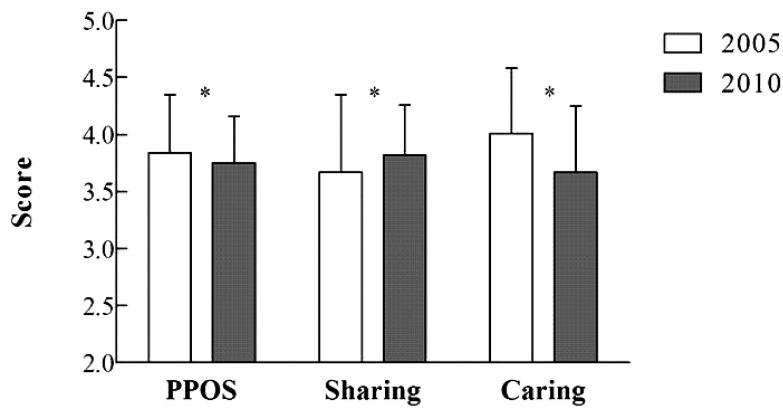

As shown in Figure 1, in phase II, as compared with phase I, the mean PPOS scores were lower (3.84 ± 0.51 vs. 3.75 ± 0.41; P = 0.004), 'sharing' scores were higher (3.67 ± 0.68 vs. 3.82 ± 0.44; P < 0.001) and 'caring' scores were lower (4.01 ± 0.57 vs. 3.67 ± 0.58; P = 0.001) after adjusting for gender, age, marital status, education level, monthly income, functional health status, and chronic diseases.

Changes in the mean PPOS score and 'sharing' and 'caring' scores over a 5-year period in primary care setting. *P < 0.01. Values are expressed after adjusting for covariates such as gender, age, marital status, education, income, functional health status, and presence of chronic diseases. PPOS: Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale.

3. The PPOS and Subscale Scores, and Their Changes Depending on Socio-Demographic Factors

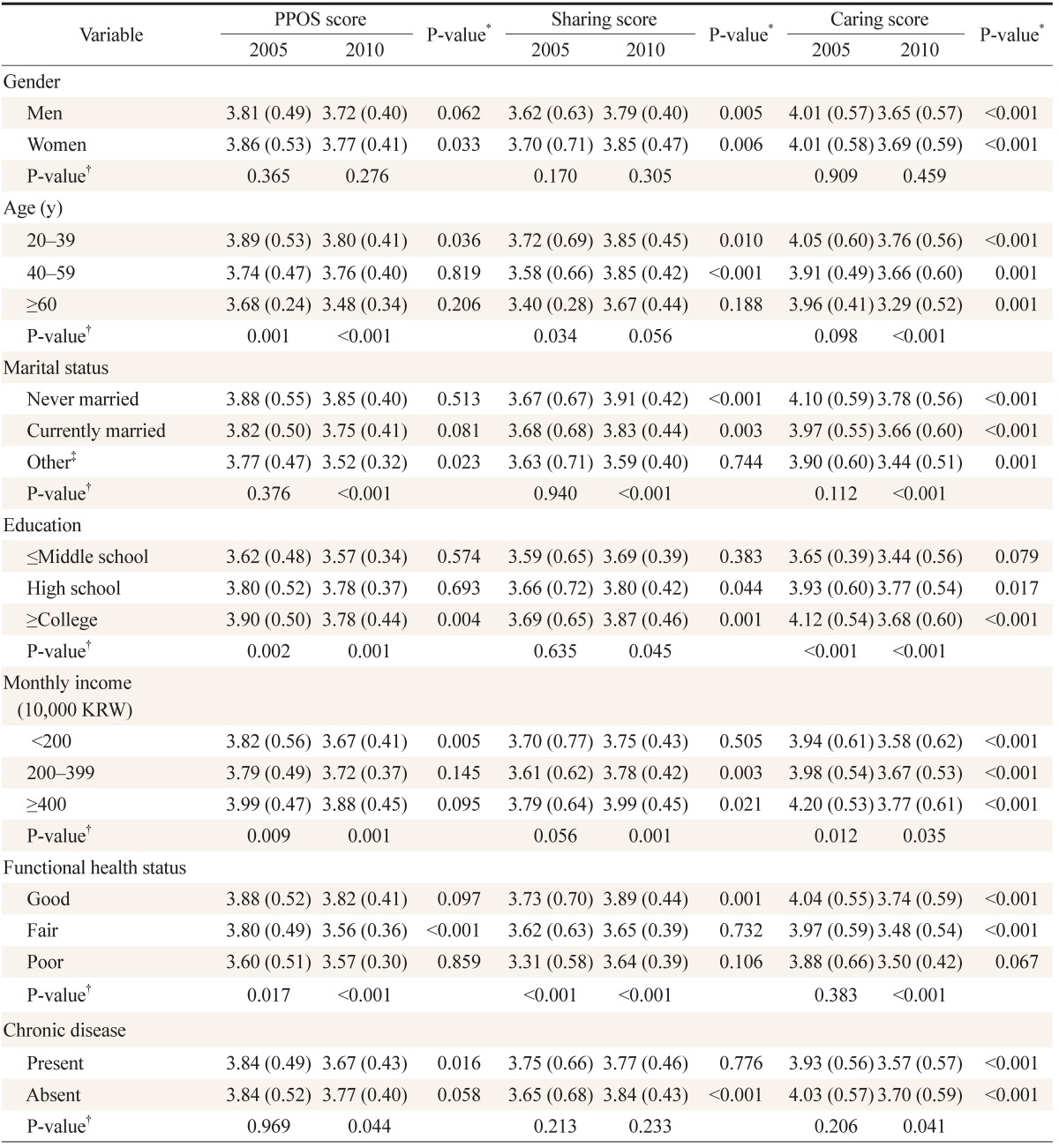

As shown in Table 2, there were no differences in the mean PPOS scores and 'sharing' and 'caring' scores between men and women in each phase. The mean PPOS scores and 'sharing' and 'caring' scores in each phase were higher in the younger patients with a higher income, higher educational level, and better functional health status. In phase II, there were differences in the mean PPOS scores and 'sharing' and 'caring' scores depending on the marital status. Specifically, they were lower in patients who were 'never married,' 'currently married,' and 'others' (separated, divorced, or widowed) in the corresponding order. In phase II, as compared with phase I, the 'sharing' scores were higher and 'caring' scores were lower in all most subgroups of patients, except for those aged 60 years or older, those who reported their marital status as 'separated,' 'divorced,' or 'widowed,' those who were educated up to 'lower than middle school level,' those with a 'low monthly income,' those with 'fair and poor function health status,' and those with chronic diseases.

4. Differences in the Degree of Patient Agreement on PPOS Items between Phase I and II

The degree of patient agreement on the items, "The doctor is the one who should decide what gets talked about during a visit" and "Although healthcare is less personal these days, this is a small price to pay for medical advances" was higher in phase II as compared with phase I (47.9% vs. 58.1%; P = 0.004, and 30.9% vs. 39.5%; P = 0.010, respectively). In contrast, as compared with that in phase I, in phase II, the degree of patient agreement was lower on the items, "When patients disagree with their doctor, this is a sign that the doctor does not have the patient's respect and trust" (45.1% vs. 38.0%; P = 0.040), "The patient must always be aware that the doctor is in charge" (54.3% vs. 47.2%; P = 0.043), "A treatment plan cannot succeed if it is in conflict with a patient's lifestyle or values" (59.9% vs. 52.1%; P = 0.026), and "Humor is a major ingredient in the doctor's treatment of the patient" (72.4% vs. 64.1%; P = 0.011) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Identifying the patients' expectations from clinical consultations could be a key factor in improving the degree of patient satisfaction with clinical outcomes and establishing a favorable relationship between clinicians and patients, especially in a continually changing medical environment. We therefore examined the change in the degree of patient expectations for patient-centered care over a 5-year period, as well as the related socio-demographic factors.

In the current study, we found that 'sharing' scores were higher in 2010 as compared to those in 2005. The degree of patient expectations for sharing medical information and the power in the decision-making process, i.e., the sharing concept, was subject to various factors such as age, education level, and other demographic characteristics, as well as their underlying medical conditions.21,22,23) However, it was interesting to note that there was a significant change in the degree of expectations even adjusting for the impact of socio-demographic factors. It is also noteworthy that the degree of patient agreement on items "When patients disagree with their doctor, this is a sign that the doctor does not have the patient's respect and trust" and "The patient must always be aware that the doctor is in charge" was lower in 2010 as compared with that in 2005. These results indicate that the degree of patients' expectations on the sharing concept increased over the 5-year period. Patients' expectations or preferences about the sharing concept has been of increasing concern due to the increased exposure to medical information through various means,11,12) the increased recognition that patients constitute an essential component of the healthcare system,10) and a consensus that they have a right to be fully informed about and share the decision-making process with clinicians.13,14) In addition, previous literature indicates that physical and psychological outcomes would be improved when medical information and the decision-making process is shared between the two parties involved.3,5,24)

Our results showed that the 'caring' score was higher than the 'sharing' one in the participants of phase I (in 2005), which was not in agreement with previous literature.15,23) In phase II (in 2010), however, the 'caring' score was lower than the 'sharing' one. This suggests that the degree of patients' concern about the clinicians' interest in patient's feelings and psychosocial perspectives was lower in 2010 than in 2005. Specifically, in 2010, as compared with 2005, the degree of patient agreement on the item "If healthcare is less personal these days, this is a small price to pay for the medical advances" was higher and that on items such as "A treatment plan cannot succeed if it is in conflict with a patient's lifestyle or values" and "A friendly manner is a major ingredient in the doctor's treatment of the patient." The probable cause for the decrease in the 'caring' score over a 5-year period could be that Korean patients think of the affectionate relationship between physicians and patients as an unrealistic thing, owing to the formal environment in the Korean medical setting (e.g., limited time for consultation).

Our results showed that the mean PPOS and subscale scores were higher in the younger patients with a higher level of education, a higher monthly income, and a higher health functional status, which is consistent with the findings of previous reports,25) but there was no sex-related difference in the scores. It is also noteworthy that there were similar trends in the changes in 'sharing' and 'caring' scores (higher 'sharing' score and lower 'caring' score over a 5-year period) in a subgroup of patients, which was assigned based on socio-demographic factors, except for a few other subgroups. As a single, standardized approach without considering the patients' expectations with reference to the related socio-demographic factors would not be consistently effective for all the patients, these results are of significance in that they might be applicable only to a specific subgroup of patients in a clinical setting.

Thus, there are some limitations to the current study. (1) We enrolled only the patients who visited the outpatient clinic of the department of family medicine in some areas. It is therefore unavoidable that a selection bias was involved in the current study. (2) We did not consider the disease-related factors, such as the severity of diseases, but evaluated the presence of chronic diseases only.

Despite these limitations, our results are of significance in that this is the first attempt to evaluate changes in the degree of expectations of patients about patient-centered care in a primary care setting. Moreover, because patient-centered care plays a pivotal role in disease prevention and health promotion,26,27,28) these findings could be a significant cornerstone in implementing patient-centered approaches in a primary healthcare setting.

To summarize, our results were as follows: (1) The 'sharing' score of patients in a primary care setting increased and 'caring' one decreased over a 5-year period. (2) The mean PPOS and subscale scores in each phase of the study were associated with some socio-demographic factors of patients, such as age, monthly income, education level, marital status, and functional health status.

In conclusion, our results suggest that clinicians need to be more flexible to adapt themselves to the patients' preferences and provide patient-centered care for patients in a primary care setting. This is possible if clinicians are aware of the degree of patients' expectations for it, which might eventually lead to the improvement of clinical outcomes as well as the relationship between the two parties.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.