INTRODUCTION

Hypersensitivity to mosquito bites (HMB) is a rare disorder characterized by intense skin responses such as erythema, bullae, ulcers, and scar formation at the sites of mosquito bites, accompanied by various simultaneous or subsequent general symptoms such as high fever, general malaise, and lymphadenopathy.1,2,3,4) To date, most reported cases of HMB have been associated with chronic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and natural killer (NK) cell leukemia/lymphoma.3,4) Although exceptional cases of HMB have been reported in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia or mantle cell lymphoma without evidence of an EBV infection, no cases of HMB associated with anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) have yet been reported.5,6) In this study, we report the first case of HMB associated with ALCL.

CASE REPORT

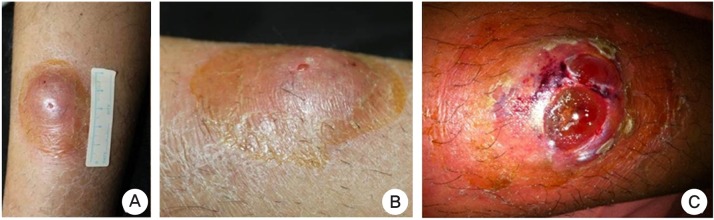

An 18-year-old Korean boy was referred to our outpatient clinic with complaints of a progressive cutaneous nodule on his left lower leg in August 2011. The lesion had developed after a mosquito bite and had been treated as a reaction to an insect bite for 1 month. Dermatological examination revealed an erosive and erythematous nodule measuring approximately 4 × 4 cm on the left lower leg (Figure 1A, B). The lesion had evolved into a necrotic and hemorrhagic ulcer (Figure 1C); on physical examination, regional lymphadenopathy was observed in the left inguinal area. Excluding the lymphadenopathy, the patient had no other systemic symptoms such as high fever, malaise, hepatosplenomegaly, hepatic dysfunction, hematuria, or proteinuria.

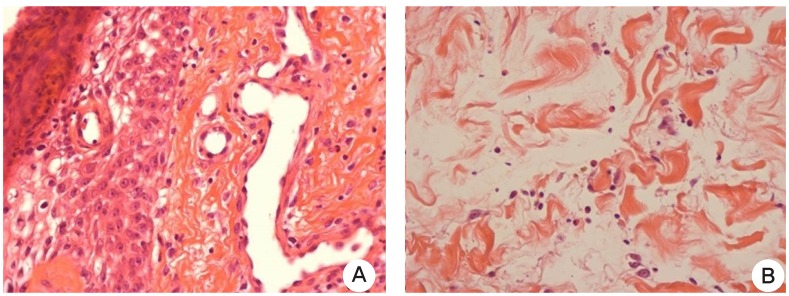

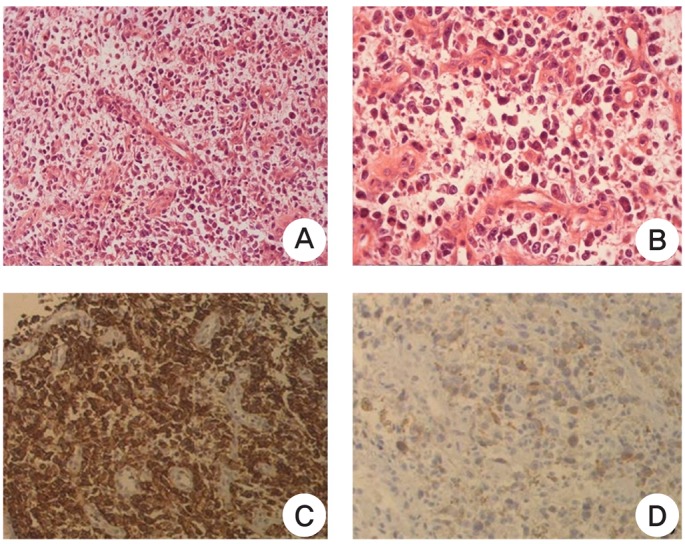

With a clinical diagnosis of secondary infection such as furuncle, deep mycosis, or mycobacteria other than tuberculosis after the mosquito bite, a skin biopsy was performed. Histopathological examination demonstrated spongiotic epidermis (Figure 2A) and infiltration of polymorphous lymphocytes around the vessels (Figure 2A), and a few eosinophils in the dermis (Figure 2B). Infiltrative sheets of medium-to-large, pleomorphic, and atypical lymphoid cells with prominent nucleoli were observed in the reticular dermis (Figure 3A, B). Immunohistochemically, all tumor cells were positive for cluster of differentiation (CD)30 (Figure 3C) and epithelial membrane antigen, and negative for CD3, CD4, CD5, CD20, and CD56 (data not shown). Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) staining (Figure 3D) revealed strong cytoplasmic, nuclear, and nucleolar reactivity of the large cells. RNA-encoding EBV genes were not detected by in situ hybridization. Southern blot analysis of the specimen confirmed gamma gene rearrangement of the T-cell antigen receptor, and monoclonal T-cell proliferation was observed. The histopathological and immunohistochemical findings confirmed the presence of ALK-positive ALCL in the skin lesion.

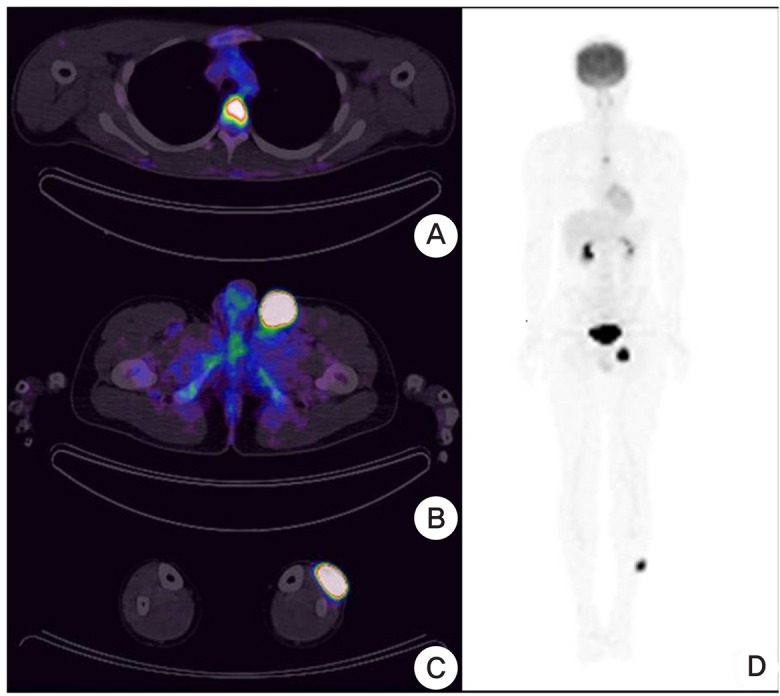

The patient was referred to the department of oncology for systemic evaluation. The bone marrow examination findings were all normal, and upon laboratory examination, the complete blood cell count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level were also within the normal ranges. Chest radiography and abdominal and pelvic ultrasonography revealed no pathological findings; however, positron emission tomography-computed tomography demonstrated increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the left T4 vertebrae, left external iliac lymph nodes, left inguinal lymph nodes, and lateral subcutaneous region of the left lower leg (Figure 4). According to the clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical findings, as well as the imaging data, the patient was diagnosed with primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL. Consequently, he received a total of 6 cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + vincristine + prednisolone) chemotherapy at 3-week intervals, after which the lesions regressed. He is currently being followed-up by the department of oncology.

DISCUSSION

HMB is defined as an intense local skin response, characterized by erythema, ulcers, bullae, necrosis, and associated general symptoms, after a mosquito bite. General symptoms such as high fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, hepatic dysfunction, hematuria, and proteinuria may be observed during the clinical course.1,2,3,4) Histologically, HMB develops as a non-neoplastic inflammatory lesion exhibiting spongiotic epidermis, dermal edema, and perivascular infiltration of lymphoid cells with irregular nuclei throughout the dermis. Some neutrophils and eosinophils may also be observed in the lesion.4,7)

Most cases of HMB have been reported in Japanese patients in the first 2 decades of life, and these cases have illustrated a close relationship between mosquito allergies and chronic EBV infection and NK cell leukemia/lymphoma.1,2,3,4) However, not all cases of HMB develop into NK cell leukemia/lymphoma.2,5,6,7,8) Shigekiyo et al.5) reported a case of HMB developing into mantle cell lymphoma, and Konuma et al.8) and Seon et al.2) also reported cases of HMB that did not develop into NK/T-cell proliferative diseases. To date, 7 patients with HMB have been reported in Korea, including 3 patients with lymphoid neoplasms such as NK cell lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma-like B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, and marginal zone B-cell lymphoma.7,9,10) In our case, the patient had HMB displaying necrotic ulceration at the site of a mosquito bite and lymphadenopathy associated with primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL.

Primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL frequently presents with extranodal involvement.11,12) In particular, skin involvement has been reported in approximately 20% to 30% of all cases.11,12) The diagnosis of primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL displaying cutaneous involvement is difficult, as it may be frequently misdiagnosed as an inflammatory disease in cases in which there is a clinical history of insect bites.12,13)

In this case, HMB was the first clinical presentation of primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL. However, whether the association with the mosquito bite was incidental or whether the mosquito bite triggered the ALCL remains to be elucidated. We cannot exclude a coincidental association, as the patient may have had an occult disease of primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL when the mosquito bit his left lower leg.14) It is possible that cytokines induced by the mosquito bite precipitated an inflow of neoplastic cells to the site of inflammation via chemotaxis.14) Alternatively, the sequential occurrence of the skin lesion following the mosquito bite and regional lymphadenopathy suggests a direct relationship between HMB and the presentation of primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL.14) Thus, we hypothesize that the mosquito bite may have triggered the presentation of primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL in the present case.

Similar cases of cutaneous presentation of primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL following insect bites have been reported in hematologic journals.13,14) In 2010, Lamant et al.14) reported five cases of ALK-positive ALCL that presented with skin lesions after bites by insects such as ticks and Clavicular wasps. Based on their review of these cases, the authors suggested a direct relationship between the bite and the presentation of primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL, proposing that insect bite-associated antigens may result in an influx of T-lymphocytes, some which may bear the t(2;5) translocation that results in the expression of the oncogenic nucleophosmin-ALK fusion protein, consequently resulting in uncontrolled proliferation.14) Likewise, we considered that there is a possibility that the mosquito bite-associated antigens triggered this case of primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL.

In conclusion, we believe that HMB and primary systemic ALK-positive ALCL may have had a causal relationship in this case, owing to the sequential occurrence of the skin lesion following a mosquito bite and regional lymphadenopathy. Further evaluation is needed to address the role of HMB in triggering skin manifestations in ALCL.