|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Volume 38(1); 2017 > Article |

Abstract

Background

We investigated the knowledge, status, and barriers toward healthcare workers receiving vaccinations among Korean family medicine residents. To date, a systematic study has not been conducted among medical practitioners examining these variables.

Methods

A web-based, anonymous, self-administered questionnaire was distributed to all 942 family medicine residents working in 123 training hospitals in Korea. A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate factors affecting vaccination completion.

Results

Korean family medicine residents (N=242, 25.7%) from 54 training hospitals (43.9%) participated in the survey. Only 24 respondents (9.9%) had correct knowledge on all the recommended vaccinations by the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases. The complete vaccination rates against hepatitis B virus and influenza were relatively high (69.4% and 83.0%, respectively), whereas they were relatively low against other infections (e.g., 16.5%– 53.1%). The most common reason for not receiving a vaccination was the belief that there was little possibility of infection from the vaccine-preventable diseases.

Conclusion

Knowledge and vaccination coverage were poor among family medicine residents in Korea. Medical schools should provide vaccination information to healthcare workers as part of their mandatory curriculum. Further research should confirm these findings among primary care physicians and other healthcare workers.

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are defined as all persons employed in a healthcare facility, including (but not limited to) physicians, nurses, pharmacists, paramedical, laboratory, administrative staff, and medical students.1) They may be exposed to and transmit vaccine-preventable diseases such as influenza, measles, rubella, and pertussis. Maintaining immunity in the HCW population helps prevent transmission of vaccine-preventable diseases between HCWs and patients. However, only a handful of studies have investigated overall immunization for HCWs.2,3,4,5,6,7) In addition, these studies were performed in a few countries in Europe,2,3,4,5) Australia,6) and South America;7) however, no studies have been conducted in the United States or Asia.

In Korea, HCW vaccination was established by the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases (KSID) for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, varicella, measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP), and influenza (annually).8) Many studies in Korea have investigated HCWs' vaccination status for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, pneumonia, or influenza;9,10,11,12) however, no study has focused on overall recommended immunization for HCWs.

Family medicine doctors, as primary care physicians, are easily exposed to many infectious diseases. It is necessary for them to receive vaccinations for their own health and the health of their patients. Additionally, they must complete vaccinations before or during the early period of their resident training. However, there has been no systematic study on the knowledge or vaccination status recommended to HCWs among family medicine residents and doctors. Investigations on family medicine residents are even more important because they provide information on the recent education programs in medical schools and training hospitals.

This study was conducted (1) to investigate knowledge on HCW vaccination and the vaccination status among family medical residents in Korea, and (2) to identify the barriers against their immunization.

A web-based, anonymous, self-administered questionnaire was distributed to all 942 family medicine residents working in 123 training hospitals in Korea in July 2014. We designed survey questions based on KSID's recommendation with reference to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States. Preliminary survey questions were created in consultation with an advisory council (2 family medicine specialists and 1 infectious medicine specialist). After a pilot study with 20 family medicine residents in Korea, the final questionnaire was completed via the advisory council. The institute ethics committee approved the study. This study's procedure followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The following data were collected from each resident: demographics and residency grade, living region, hospital training level, length of medical career in years, history of natural infection, knowledge and information source on vaccines recommended for HCWs, the number of vaccinations received, a serology test after hepatitis B vaccination, and barriers to vaccination. Based on the KSID recommendations, we further checked the MMR vaccination history using medical records or vaccination booklets.

Complete vaccination was defined as follows: 2 doses of hepatitis A vaccine, 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine and a serology check for seroconversion, 2 doses for varicella vaccination for HCWs born after 1970, 2 doses of MMR for HCWs born after 1967, 1 dose of adult DTP vaccine (introduced in 2008 in Korea), and an influenza vaccine received during the past 12 months. Incomplete vaccination indicated an insufficient number of vaccinations, an incomplete vaccine (i.e., tetanusdiphtheria vaccine instead of tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis vaccine), or an unconfirmed hepatitis B surface antibody. Self-reported immunity against vaccine-preventable diseases was defined as either a history of natural infection leaving permanent immunity and/or a history of completed, up-to-date vaccination.

Frequencies and means were used for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. A multiple logistic regression analysis was applied to investigate factors significantly associated with HCWs' vaccination state, which included age, sex, residency grade, living region, hospital training level, years as a doctor, correct knowledge state for each HCW vaccination, and an antibody test. For all statistical analyses, Stata software ver. 10.0 (Stata Co., College Station, TX, USA) was used. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

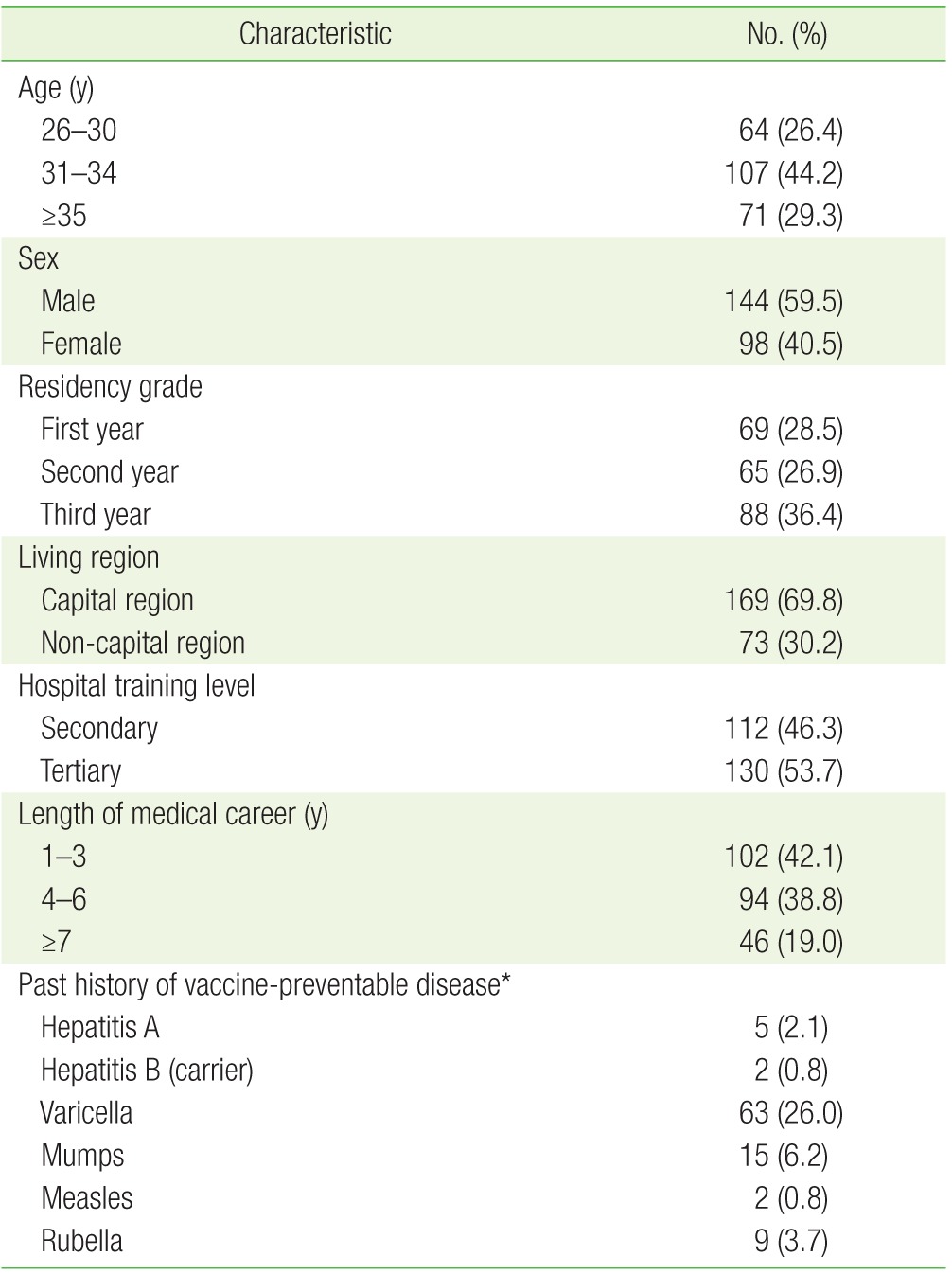

Korean family medicine residents (N=242, 25.7%; 144 males and 98 females) from 54 training hospitals (43.9%) participated in the survey. Table 1 shows participants' baseline characteristics. The mean age of participants was 32.8±3.8 years (range, 26 to 48 years). The majority of subjects (69.8%) were living in the capital region (Seoul, Incheon, or Gyeonggi-do). The highest frequency of the history of disease was varicella (26.0%, 63/242), followed by mumps (6.2%, 15/242), and rubella (3.7%, 9/242). No participants reported a past history of diphtheria, tetanus, or pertussis.

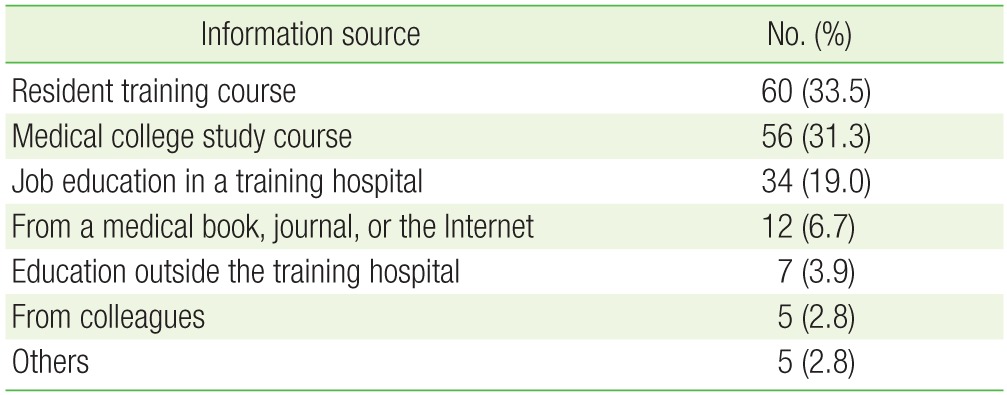

Table 2 presents the information source regarding HCW vaccination. Of all participants, 73.9% (179/242) had ever been informed about HCW vaccination. Most of them had information from the resident training course (33.5%), medical college (31.1%), and job education in the training hospital (19.0%). Overall, only 56 subjects had been informed by medical colleges which corresponded to 23.1% of all participants.

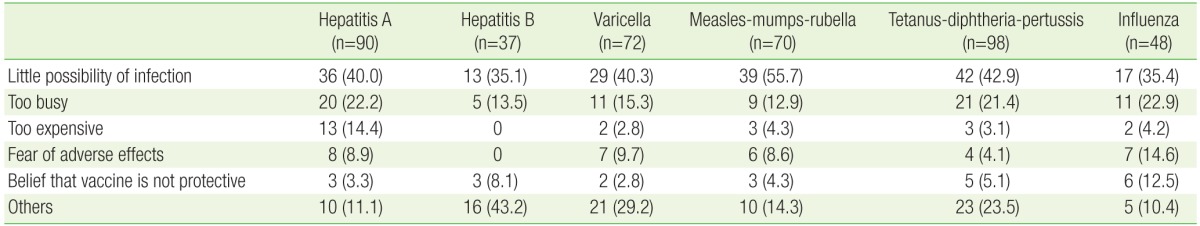

Only 24 HCWs (9.9%) answered correctly on all 6 KSID recommended vaccinations. Most HCWs were aware of the recommendations for vaccination against hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and seasonal influenza (77.3%, 92.2%, and 89.2%, respectively); however, the percentage of correct answers for other vaccines were relatively low (51.2%–57.9%). Table 3 summarizes the correct knowledge about HCW vaccination based on KSID.

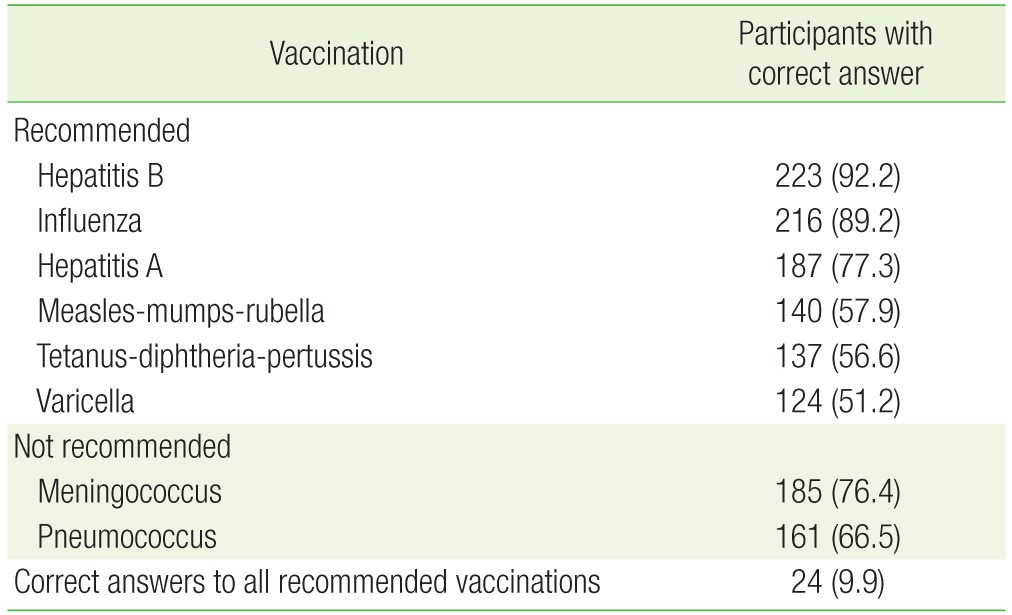

Table 4 shows participants' complete and incomplete vaccination rate based on KSID's recommendation. Carriers for hepatitis B virus, participants with past history for each viral disease, or non-respondents were excluded from the analysis. While the complete vaccination rates against hepatitis B and influenza were high (69.4% and 83.0%, respectively), that against DTP was the low (16.5%). More than half of all subjects (53.1%) had completed MMR vaccination; only 9.4% of respondents could prove vaccination status by medical records or vaccination record book.

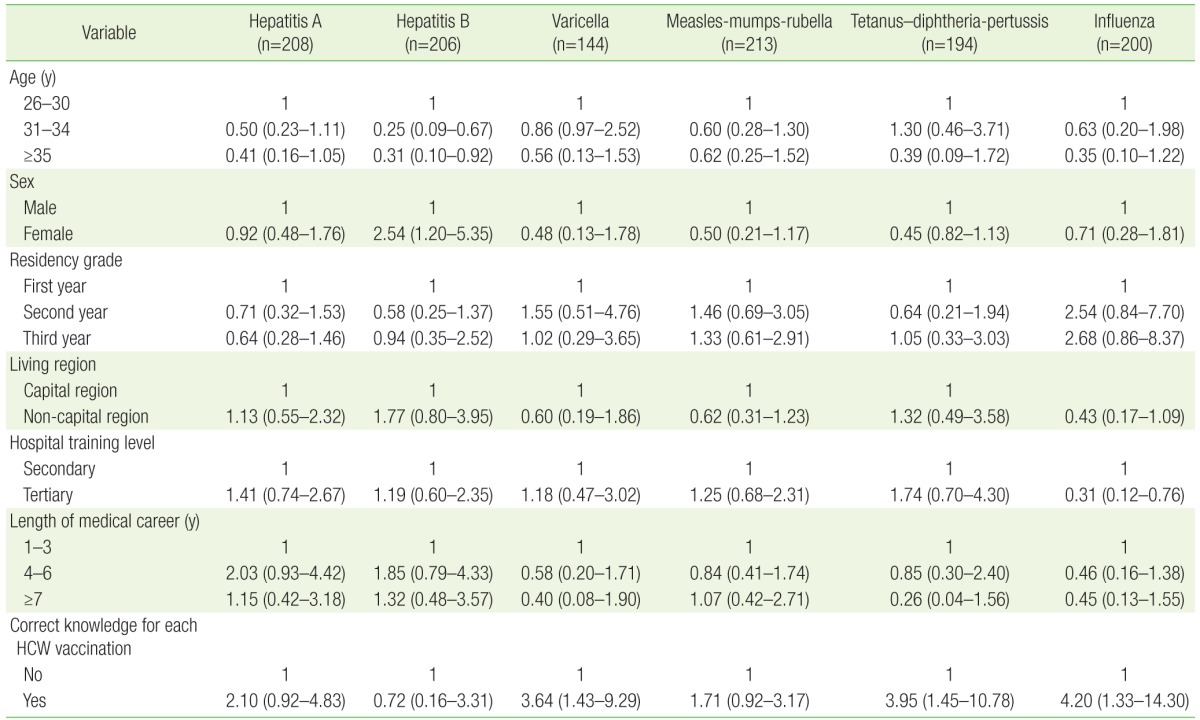

Table 5 presents multivariate logistic regression analyses on the association between various factors and completed vaccination against target diseases. Compared with the <30-year-old group, the ≥31 yearold groups showed a significantly lower vaccination rate (odds ratio [OR], 0.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.09 to 0.67 in age of 31–34; OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.10 to 0.92 in age of 35 or more). Females showed a significantly higher hepatitis B vaccination status than males did (OR, 2.54; 95% CI, 1.20 to 5.35). Respondents working in tertiary hospitals had a lower influenza vaccination rate than those in secondary hospitals did (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.76). Those who had correct knowledge on the recommended vaccine showed a higher vaccination rate than those who had incorrect knowledge on varicella, DTP, and influenza (OR, 3.64; 95% CI, 1.43 to 9.29; OR, 3.95; 95% CI, 1.45 to 10.78; OR, 4.20; 95% CI, 1.33 to 14.30, respectively). A multiple logistic regression analysis revealed no associations between vaccination rate and residency grade, living region, or length of career as a doctor.

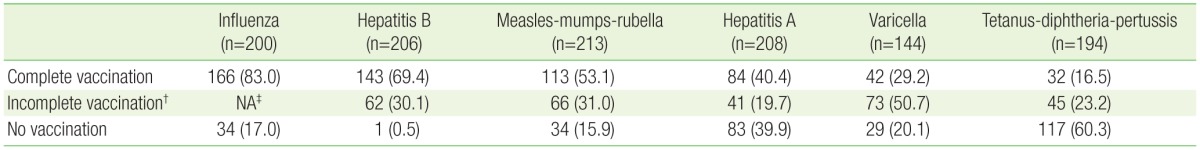

The most common reason for not completing vaccination was ‘they have little possibility of infection’ (35.1%–55.7% depending on each vaccine). The second most common barrier that prevented vaccination was that ‘they are too busy.’ These rates ranged from as low as 12.9% for MMR to 22.9% for influenza. Fourteen-point-four percent answered that ‘it is too expensive to get vaccination’ for hepatits A. Of the 48 subjects who did not complete the influenza vaccination, 7 (14.6%) stated ‘concern about adverse reactions’ for influenza vaccine. Table 6 summarizes the barriers that prevented vaccination for each HCW.

In this study, only 9.9% of participants had correct knowledge on HCW vaccinations recommended by the KSID. Compared to the level of correct knowledge on HCW vaccination, vaccination rates were relatively low, except for influenza and hepatitis B. The major cause for not completing vaccination was their belief that they have little possibility of infection by vaccine-preventable diseases.

Among vaccinations recommended for HCWs, vaccination against hepatitis A and B required 6 months; furthermore, for hepatitis B, an additional 6 months may be needed for revaccination according to the results of a serology test. Given the long period to complete vaccinations, education on HCW vaccination should be part of their training at medical schools. Unfortunately, only 23.1% of the participants had received this information in school. If possible, this information should be included in as part of the mandatory curriculum.

Of note, this study indicated that knowledge about HCW vaccinations was extremely low (9.9%). A similar tendency was reported in other countries: only 12.9% of HCWs in primary healthcare centers in Greece correctly named the 3 vaccines recommended for HCWs;13) another study in a French hospital showed that only 25% of HCWs were able to list the 3 mandatory vaccines for HCWs.2) Therefore, the public health authority of each country should pay attention to this issue and establish new continuing education programs on HCW vaccination.

Regarding complete vaccination rate, we found that influenza was the highest (83%); this was followed by hepatitis B, MMR, and hepatitis A (69.4%, 53.1%, and 40.4%, respectively); varicella and DTP were the lowest (29.2% and 16.5%, respectively). According to a 2003 study conducted at a university hospital in Korea, HCWs' hepatitis B antibody positive rate was similar (76.9%).10) HCWs' self-reported vaccination rates against hepatitis B ranged from 40% to 95%, worldwide.6,13) Despite the reported high rates of knowledge on HCW vaccination against hepatitis B (92.2%), only 69.4% completed hepatitis B vaccination based on KSID recommendations. Similarly, comparable discordance between belief and action was reported in a hospital in Australia, where only 18% of 269 HCWs were fully vaccinated despite their high (94%) rate of stated belief in the importance of full vaccination.6) Likewise in Greece, despite high rates of knowledge about vaccination of HCW against hepatitis B and influenza (81.2% and 75.4%, respectively), almost half of the HCWs were not vaccinated against hepatitis B, and 60% had never received an influenza shot.14) Globally, HCWs' voluntary compliance with influenza vaccination rarely exceeds 40%.3) Our study, on the other hand, showed a high rate of knowledge and vaccination against influenza (89.2% and 83%, respectively). The high vaccination rate of influenza may have originated from a free vaccine supplied by the working hospital annually. This observation was in line with a previous study in Korea.12)

Our data revealed that both knowledge and vaccination rate for varicella, DTP, and MMR were relatively low. The self-reported susceptibility rates against MMR, and varicella ranged from 12.7% to 18.9% in other countries.15,16,17) Given the seriousness of these viral illness in adulthood and the recent outbreaks of measles and pertussis in Korea,18,19) the importance of these vaccines must be as equally emphasized as hapatitis A, hepatitis B, or influenza vaccines are. Notably, there were recent measles, mumps, and rubella epidemics in Europe and the United States;20,21,22,23) therefore, vaccination against such diseases is of particular importance because of the increase in overseas travel to these countries.

Of these vaccinations, the complete vaccination rate against MMR (53.1%) may be incorrect. Historically, the MMR vaccine was introduced to Korea in 1980 and recommended at only one dose initially. Since 1997, the second dose was added at the age of 4–6 years. All respondents in this study were older than 6 years old. During medical school, most respondents learned that the national childhood immunization program recommends 2 doses of MMR vaccines; therefore, they might have confused their doses of MMR vaccine as two and incorrectly reported the number of MMR vaccines, which led to an overestimation of the MMR vaccination rate. Despite the additional MMR vaccination in women of childbearing age, it is still an important issue and warrants future investigation.

We evaluated the factors associated with complete vaccinations rates in the study group. Our data showed that the older age group (>30 years) had a significantly lower hepatitis B vaccination rate. A similar tendency was also noted in other Korean and foreign studies.11,14) Unexpectedly, respondents working in secondary hospitals, rather than tertiary hospitals, had a higher influenza vaccination rate. It is likely that residents in tertiary hospitals were busier and had more limited access to influenza vaccination than those in secondary hospitals did. This result was consistent with a previous study on influenza vaccination in a Korean tertiary hospital.12) Correct knowledge about HCW vaccination showed a higher vaccination rate among hepatitis A, varicella, DTP, and influenza. This requires more attention because they are modifiable factor. A recent study conducted in a tertiary hospital in Korea showed that a strong hospital campaign increased HCWs' influenza vaccination rate from 27% to 52%.24)

The most common reason for not completing a vaccination was that participants felt they had a small possibility of infection. This response suggested that most family medicine residents in Korea might have not properly understood the meaning of the recommended vaccination. Maintaining immunity among HCWs helps prevent transmission of vaccine-preventable diseases from them to patients. In addition, it provides self-protection. Contrarily, studies conducted in United States25) and Australia6) indicated concerns about vaccine side effects as the most important barrier.25,26) However, since our study only included doctors, the results are not entirely generalizable. Another main barrier that prevented vaccination is that doctors are too busy (this response ranged from 12.9% for MMR to 22.9% for influenza). Another Korean study supported this concept of being too busy (37.3% in all HCWs and 68.8% in doctors).12) This indicates that there is time or spatial constraint to vaccination in the workplace. Hence, it may be a realistic and practical method for the hospital injection team to visit doctors' clinics and wards to directly perform the vaccinations.12) Cost is another problem that prevents vaccination, especially for hepatitis A. Many studies demonstrated that the highest level of coverage is reached when the vaccine is provided free of charge after extensive education.24,27,28)

An education program should be considered by public health authorities to increase HCWs' vaccination rate. The cost required for such a program is likely to be small compared with the cost of vaccine-preventable illnesses among HCWs and patients in terms of morbidity, mortality and lost productivity.

There were several limitations to this study. The immunization data was self-reported and not verified by vaccination booklets, medical records, or serology tests. Recall bias may have interfered with the representativeness of these results; those who were more interested in HCW vaccination or who did not complete the vaccination may have participated actively in the survey. The relatively low response rate was another limitation. In addition, the study sample was not evaluated for the representativeness of source population in terms of socio-demographic characteristics; however, the moderately large number of training hospitals used may compensate for this flaw.

Nevertheless, this is the first study that addressed the overall HCW vaccination rate of doctors in Asia and the only study that was conducted among family medicine residents in the world. In addition, we considered various factors associated with completed vaccination.

In conclusion, knowledge and vaccination coverage were poor among family medicine residents in Korea. The education program in medical schools should include teaching future HCWs about vaccinations as part of their mandatory curriculum. Further research is required to confirm these findings among primary care physicians and other healthcare workers.

References

1. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Immunization of health-care personnel: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2011;60(RR-7):1-45.

2. Loulergue P, Moulin F, Vidal-Trecan G, Absi Z, Demontpion C, Menager C, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and vaccination coverage of healthcare workers regarding occupational vaccinations. Vaccine 2009;27:4240-4243. PMID: 19481314.

3. Tafuri S, Martinelli D, Caputi G, Arbore A, Lopalco PL, Germinario C, et al. An audit of vaccination coverage among vaccination service workers in Puglia, Italy. Am J Infect Control 2009;37:414-416. PMID: 19216005.

4. Maltezou HC, Gargalianos P, Nikolaidis P, Katerelos P, Tedoma N, Maltezos E, et al. Attitudes towards mandatory vaccination and vaccination coverage against vaccine-preventable diseases among healthcare workers in tertiary-care hospitals. J Infect 2012;64:319-324. PMID: 22198739.

5. Bader HM, Egler P. Immunisation coverage in the adult workforce 2003: utilisation of routine occupational health checks to ascertain vaccination coverage in employees. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2004;47:1204-1215. PMID: 15583892.

6. Murray SB, Skull SA. Poor health care worker vaccination coverage and knowledge of vaccination recommendations in a tertiary Australia hospital. Aust N Z J Public Health 2002;26:65-68. PMID: 11895030.

7. Silveira MB, Perez DA, Yamaguti A, Saraiva EZ, Borges MG, de Moraes-Pinto MI. Immunization status of residents in pediatrics at the Federal University of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2011;53:73-76. PMID: 21537753.

8. Kang JH, Kim HB, Sohn JW, Lee SO, Chung MH, Cheong HJ, et al. Adult immunization schedule recommended by the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases, 2007. Infect Chemother 2008;40:1-13.

9. Yoon HJ, Lim J, Choi B, Kim J, Kim J, Kim C, et al. Vaccination rates and related factors among health care workers in South Korea, 2009. Am J Infect Control 2013;41:753-754. PMID: 23660111.

10. Shin BM, Yoo HM, Lee AS, Park SK. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus among health care workers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2006;21:58-62. PMID: 16479066.

11. Jung SI, Lee CS, Park KH, Kim ES, Kim YJ, Kim GS, et al. Sero-epidemiology of hepatitis A virus infection among healthcare workers in Korean hospitals. J Hosp Infect 2009;72:251-257. PMID: 19446368.

12. Cheong HJ, Sohn JW, Choi SJ, Eom JS, Woo HJ, Chun BC, et al. Factors influencing decision regarding influenza vaccination: a survey of healthcare workers in one hospital. Infect Chemother 2004;36:213-218.

13. Dannetun E, Tegnell A, Torner A, Giesecke J. Coverage of hepatitis B vaccination in Swedish healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect 2006;63:201-204. PMID: 16621139.

14. Maltezou HC, Katerelos P, Poufta S, Pavli A, Maragos A, Theodoridou M. Attitudes toward mandatory occupational vaccinations and vaccination coverage against vaccine-preventable diseases of health care workers in primary health care centers. Am J Infect Control 2013;41:66-70. PMID: 22709989.

15. Trevisan A, Frasson C, Morandin M, Beggio M, Bruno A, Davanzo E, et al. Immunity against infectious diseases: predictive value of self-reported history of vaccination and disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007;28:564-569. PMID: 17464916.

16. Dinelli MI, Moreira Td, Paulino ER, da Rocha MC, Graciani FB, de Moraes-Pinto MI. Immune status and risk perception of acquisition of vaccine preventable diseases among health care workers. Am J Infect Control 2009;37:858-860. PMID: 19608297.

17. Asari S, Deguchi M, Tahara K, Taniike M, Toyokawa M, Nishi I, et al. Seroprevalence survey of measles, rubella, varicella, and mumps antibodies in health care workers and evaluation of a vaccination program in a tertiary care hospital in Japan. Am J Infect Control 2003;31:157-162. PMID: 12734521.

18. Kim JW. Report of Yeongam pertussis epidemiological investigation in Korea [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [cited 2014 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/info/CdcKrInfo0301.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU1132-MNU1138-MNU0037-MNU1380&cid=17359

19. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigation result of a small size measles outbreak in two difference provinces in Korea, 2013 [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [cited 2014 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/intro/CdcKrIntro0201.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU1154-MNU0005-MNU0011&cid=21098

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: mumps outbreak: New York and New Jersey, June 2009-January 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59:125-129. PMID: 20150887.

21. Pervanidou D, Horefti E, Patrinos S, Lytras T, Triantafillou E, Mentis A, et al. Spotlight on measles 2010: ongoing measles outbreak in Greece, January-July 2010. Euro Surveill 2010;15:19629PMID: 20684816.

22. Richard JL, Masserey Spicher V. Large measles epidemic in Switzerland from 2006 to 2009: consequences for the elimination of measles in Europe. Euro Surveill 2009;14:19443PMID: 20070934.

23. D'Agaro P, Dal Molin G, Zamparo E, Rossi T, Micuzzo M, Busetti M, et al. Epidemiological and molecular assessment of a rubella outbreak in North-Eastern Italy. J Med Virol 2010;82:1976-1982. PMID: 20872726.

24. Song JY, Park CW, Jeong HW, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ, Kim SR. Effect of a hospital campaign for influenza vaccination of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2006;27:612-617. PMID: 16755482.

25. Christian MA. Influenza and hepatitis B vaccine acceptance: a survey of health care workers. Am J Infect Control 1991;19:177-184. PMID: 1833994.

26. Habib S, Rishpon S, Rubin L. Influenza vaccination among healthcare workers. Isr Med Assoc J 2000;2:899-901. PMID: 11344770.

27. Lindley MC, Horlick GA, Shefer AM, Shaw FE, Gorji M. Assessing state immunization requirements for healthcare workers and patients. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:459-465. PMID: 17533060.

28. Canning HS, Phillips J, Allsup S. Health care worker beliefs about influenza vaccine and reasons for non-vaccination: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:922-925. PMID: 16102143.

Table 3

Correct knowledge about healthcare worker vaccination based on the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases (N=242)

Table 4

Participants with complete and incomplete healthcare worker vaccination based on the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases recommendation*

Values are presented as number (%).

*Participants with a history of each viral disease, carriers for the hepatitis B virus, or non-respondents were excluded from the analysis. †Incomplete vaccination indicates that participants with an insufficient number of vaccination, an incomplete vaccine (i.e., diphtheria-tetanus instead of tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis), or an unconfirmed hepatitis B surface antibody. ‡Not applicable due to ineffectiveness of previous vaccinations more than 6 months ago.

- TOOLS