The Association between Smoking Status and Influenza Vaccination Coverage Rate in Korean Adults: Analysis of the 2010–2012 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Article information

Abstract

Background

Globally, smoking is one of the biggest challenges in public health and is a known cause of several important diseases. Influenza is preventable via annual vaccination, which is the most effective and cost-beneficial method of prevention. However, subjects who smoke have some unhealthy behaviours such as alcohol, low physical activity, and low vaccination rate. In this study, we analyzed the relationship between smoking status and factors potentially related to the influenza vaccination coverage rate in the South Korean adult population.

Methods

The study included 13,565 participants aged >19 years, from 2010 to 2012 from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Univariate analyses were conducted to examine the association between influenza coverage rate and related factors. Multivariate analysis was obtained after adjusting for variables that were statistically significant.

Results

The overall vaccination rate was 27.3% (n=3,703). Older individuals (P<0.0001), women (P<0.0001), non-smokers (P<0.0001), light alcohol drinkers (P<0.0001), the unemployed (P<0.0001), and subjects with diabetes mellitus (P<0.0001), hypercholesterolemia (P<0.0001), and metabolic syndrome (P<0.0001) had higher influenza vaccination coverage than the others. In multivariate analyses, current smokers and heavy smokers showed lower vaccination rates (odds ratio, 0.734; 95% confidence interval, 0.63–0.854).

Conclusion

In the current study, smokers and individuals with inadequate health-promoting behaviors had lower vaccination rates than the others did.

INTRODUCTION

Smoking is known as one of the main causes of respiratory and circulatory diseases, and other chronic diseases. It is one of the biggest public health threats globally, with a mortality of approximately 6 million people yearly.12) More than 5 million of these deaths are the result of direct smoking while more than 600,000 are the result of non-smokers being exposed to second-hand smoke.1)

In Korea, the smoking rate is 19.9%, which is a high rate among the countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).3) The smoking rate is increasing in women. The Korean female smoking rate from the OECD health data were only 5.2% and is lower than the average for OECD countries (16.8%). However, when the smoking status was verified with a chemical diagnosis method, it was reported as 14.8%.45)

Several previous studies have shown that influenza vaccination is a highly safe and cost-effective for preventing the spread of infection.6789) On the basis of these studies, World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recommended annual vaccination for pregnant women at any stage of pregnancy, children aged 6 months to 5 years, elderly individuals aged more than 65 years, individuals with chronic medical conditions, and healthcare workers.10)

On the basis of this recommendation, the South Korean government provides free vaccination services at public health centers for children younger than 1 year and elderly individuals aged more than 65 years.11) Despite these efforts, the influenza vaccination coverage rate of South Korea is only 34.3%.12)

Increasing vaccination coverage rate is important to improve global public health; however, smoking is known to have a negative effect on vaccination efficacy and the prevention of influenza infection as evidenced by some studies.13141516)

Therefore, we have examined the association between vaccination rate and smoking and factors potentially related to the influenza vaccination coverage rate in the South Korean adult population using representative sample data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES).17)

METHODS

1. Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

This study is based on the KNHANES V (2010–2012). KNHANES is a yearly survey conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare; it is a crosssectional, representative, and reliable study providing a basic overview of the health policy. The survey includes health and household interviews, nutrition surveys, and direct standardized physical examinations. The stratified and multistage clustered probability sampling regarding age, gender, and geographic area was applied to represent the civilian, non-institutionalized Korean population. In addition, it produces statistics regarding smoking, drinking, physical activities, and obesity as requested by WHO and OECD. All the participants of the survey provided written informed consent and the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention approved the study protocol (2010-02CON-21-C, 2011-02CON-06-C, and 2012-01EXP-01-2C). Interviews were performed using a structured questionnaire.

2. Subjects

A total of 7,680 households were included in the KNHANES V. The sampling was weighted to represent all of the South Korean population taking the complex sampling design, oversampling, and survey non-response into consideration. Initially, 17,476 participants were enrolled. We excluded 3,911 participants who were younger than 19 years. In all, 13,565 participants were included in this study.

3. Anthropometric Measurement

Participant height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg by a trained examiner, with participants wearing light clothes. Waist circumference (cm) was also measured by a trained examiner at the mid-level between the costal margin and the iliac crest after normal expiration. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by the square of height (m2).

4. Sociodemographic Factors

Participant demographic variables were age, sex, education level, and household income. Education level and household income were used as indicators of socioeconomic status. Level of education was classified into two groups: graduated and not graduated from high school. Household income was divided into quartiles. Heavy drinking was defined as a man who drank more than 30 g of alcohol a day and a woman who drank more than 20 g of alcohol a day. Regular exercise was defined as exercising more than three times a week, and for more than 30 minutes at a time. Occupation was simply defined as those who had an occupation as against those who did not.

5. Vaccination

Information on the seasonal influenza vaccination status in the past 12 months was obtained.

6. Smoking and Comorbidities

Smoking status was classified into three groups: non-smokers, exsmokers, and current smokers. Those who had smoked more than five packs in a lifetime were defined as smokers. Ex-smokers were distinguished from current smokers, based on their present smoking status, as subjects who ceased smoking at the survey time, regardless of duration.

Diabetes mellitus (DM), hypercholesterolemia, and metabolic syndrome were also included to represent the populations who had or did not have a chronic disease. Obesity was defined as ≥25 kg/m2. DM and hypercholesterolemia were defined based on a doctor's diagnosis and metabolic syndrome was defined according to the definition of the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement.18) Central obesity for the Asian population was defined as men and women with an abdominal circumference >90 cm, and >80 cm, respectively.

7. Statistics

General characteristics according to influenza vaccination status are presented as percentages (standard errors [SE]) and as means and SE for quantitative variables. To perform group comparisons, the chi-square test and t-test were used for categorical and continuous data, respectively, and both univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate smoking and other demographic variables as factors related to influenza vaccination.

In the multiple logistic regression analyses, we adjusted for age, sex, education level, and household income as related demographic factors and used BMI, regular exercise, and drinking status as healthy behavior factors. Additionally, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for influenza vaccination coverage were calculated according to the combinations of those factors.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS ver. 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics

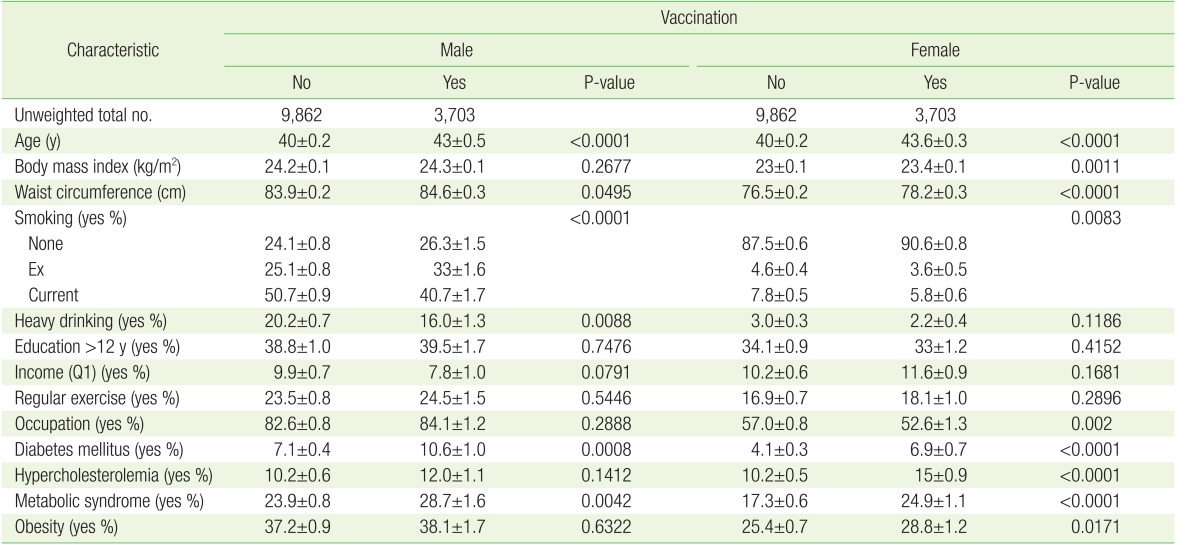

The general characteristics of the influenza vaccination coverage are shown in Table 1. Of the 13,565 participants included in this study, the vaccination coverage rate in the previous 12 months was 27.3% (n=3,703). The sexes (male and female) were analyzed separately. In men, older age (P<0.0001), non-smokers (P<0.0001), non-heavy alcohol drinking (P<0.0001), unemployment (P<0.0001), DM (P<0.0001), and metabolic syndrome (P<0.0001) were associated with higher influenza vaccination coverage. However, no statistically significant difference was observed for education level, BMI, household income, regular exercise, and hypercholesterolemia with regard to vaccination coverage.

In women, older age (P<0.0001), non-smokers (P=0.0083), occupation (P=0.002), DM (P<0.0001), hypercholesterolemia (P<0.0001), and metabolic syndrome (P<0.0001) were associated with higher vaccination coverage rate. No statistically significant difference was observed for education level, BMI, household income, regular exercise, and non-heavy alcohol drinking groups with regard to vaccination coverage.

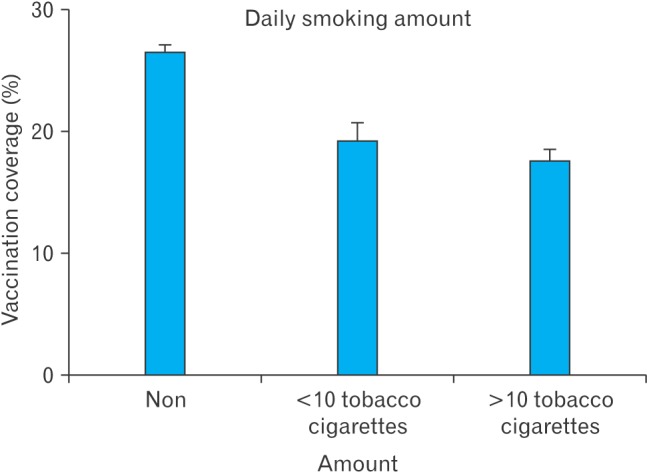

As shown in Figure 1, the vaccination coverage rate decreased as the smoking level increased (no smoking, <10 cigarettes, and >10 cigarettes). Individuals who smoked more showed a lower coverage rate than the individuals who smoked less. Non-smokers (P<0.0001) also showed a higher vaccination rate.

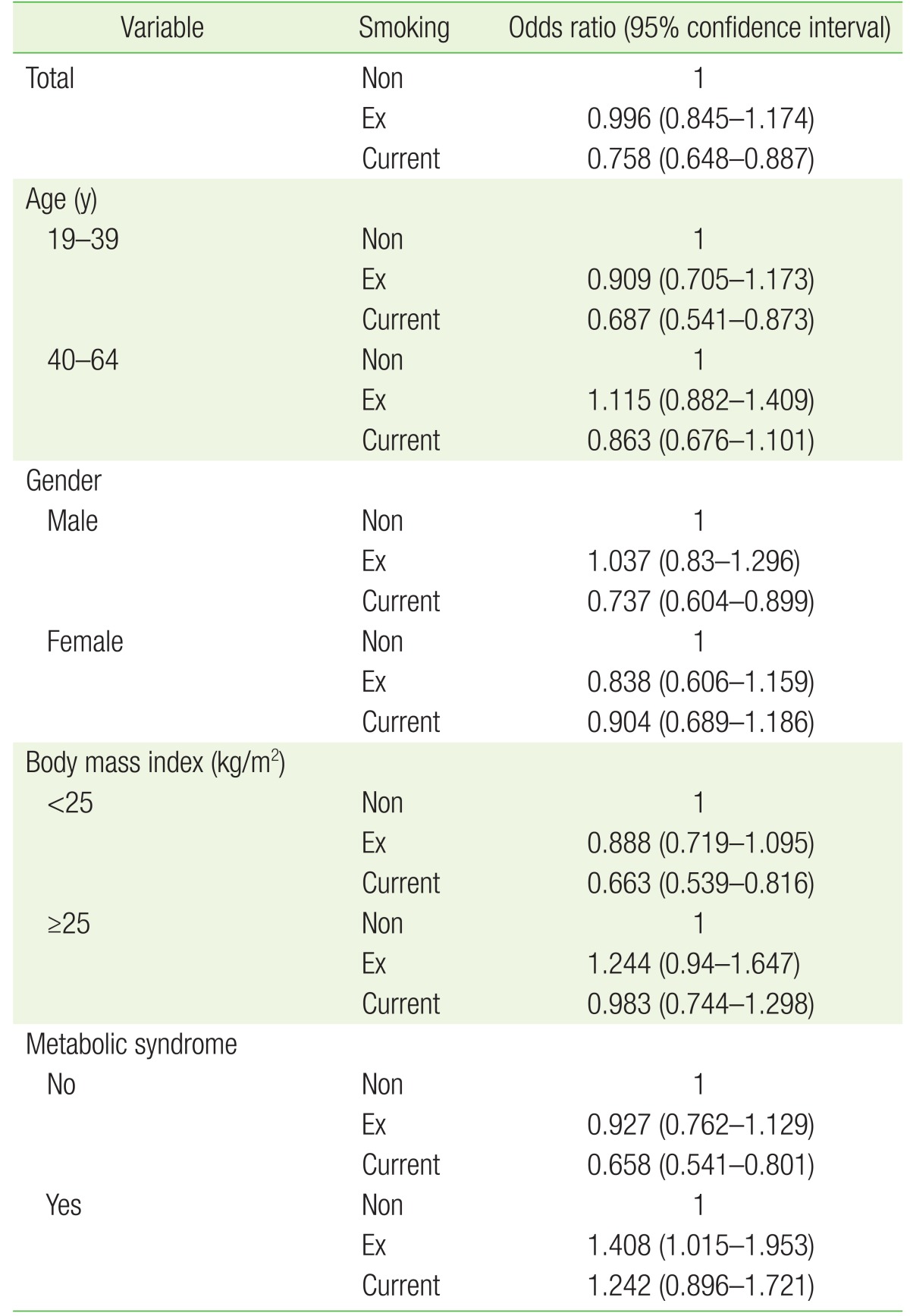

We analyzed vaccination coverage with smoking status and each of the related factors (age, sex, BMI, and metabolic syndrome). As shown in Table 2, current smokers who were younger (OR, 0.687; 95% CI, 0.541–0.873), male (OR, 0.737; 95% CI, 0.604–0.899), with lower BMI (OR, 0.663; 95% CI, 0.539–0.816), and without metabolic syndrome (OR, 0.658; 95% CI, 0.541–0.801) had lower vaccination coverage rates, while no significant effects were observed for other factors. In contrast, participants in the ex-smoker group who had metabolic syndrome showed a notably positive and significantly high coverage rate (OR, 1.408).

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3), model 2 was adjusted for age and sex; model 3 for age, sex, BMI, heavy drinking status, and regular exercise; and model 4 was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, heavy drinking status, regular exercise, education level, income, and metabolic syndrome. Current smokers had a lower vaccination rate after adjusting for all those covariates (OR, 0.753; 95% CI, 0.64–0.88).

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to demonstrate the relationship between smoking status and influenza vaccination rate. In this study, we observed that as smoking increased, the vaccination rate decreased in male current smokers. Younger age, heavy drinking, and the absence of metabolic syndrome were associated with lower vaccination rates in the South Korean adult population.

In previous studies, influenza vaccination coverage was explained as a very effective and safe preventive method; as high mortality due to influenza could be reduced by 80%, this method is recommended globally.192021)

The results of this study showed that vaccination rate was high in women, the unemployed, the diabetic, those with metabolic syndrome, non-smokers, and non-heavy drinkers.

Considering factors associated with high vaccination rates, the results were contrary to the results of the studies conducted abroad,1921) but were consistent with the results of studies conducted in Korea,2223) indicating the likelihood that women can access a range of media and visit medical institutions in their spare time, which may explain why the unemployed showed a high vaccination rate; and women tend to have more interest in their health than men.24)

Additionally, the social status of women affected their visiting medical institutions, which might have caused the difference in vaccination rate compared with results of studies conducted abroad.25) High educational level and household income were associated with high vaccination rates, indicating that those who have more time to obtain knowledge about their health make more efforts to prevent diseases.26)

For medical causes, patients with diabetes and metabolic syndrome showed higher vaccination rate, indicating the likelihood that these people tend to visit medical institutions more frequently, and are, therefore, well informed about the danger of influenza and its complications by medical service personnel.

With respect to health behaviors, non-smokers, light drinkers, and individuals who exercised regularly showed high vaccination rates, as consistent with the results of preceding studies. These groups had considerable interest in their health and practices, and this can be interpreted to have the same implication as the above-mentioned causes.2728)

In this study, a logistic regression analysis was conducted on smoking status and several related factors. The results showed that vaccination rate was low in current smokers in most groups and in the non-obese, which is consistent with the results of preceding studies.132226)

However, these results are contradicted by those of other studies in which the relationship between smoking and vaccination rate were examined where smokers seemed to recognize their increased susceptibility to infectious disease due to smoking history, leading to increased vaccination rates. Conversely, for non-smokers, their concern for their health seemed low with consequently low vaccination rates.28)

It is worth noting that vaccination rate was low in subjects without metabolic syndrome but non-smokers with metabolic syndrome showed a higher vaccination rate, indicating that this group of subjects had a greater interest in their health owing to the national interest in metabolic syndrome and health promotion campaigns.

In summary, the vaccination rate was higher in the individuals with access to information on health and in individuals exposed to situations that may have led to the increase in sensitivity.

This is the first report on the relationship between smoking status and influenza vaccination rate with the adjustment of related cofactors in the South Korean adult population using the nationally representative survey data.

However, this study has some limitations. First, all the data were collected through a questionnaire survey and analyzed retrospectively, which may have caused recall bias on a range of variables. Second, chronic diseases in smokers were not taken into consideration. Thus, there is a necessity for a subdivided survey on diseases that may result from respiratory diseases and influenza, and on the vaccination rate for these diseases.

Third, those older than the age of 65 are provided with free vaccination in Korea. This was not included in this study because many studies have been conducted involving this age group. The last limitation is that this study had a cross-sectional design making it difficult to explain a direct cause and effect relationship.

In conclusion, current smokers showed lower vaccination rate than other smokers. In smokers or in those with inadequate health-promoting behaviors, there was a difference in vaccination rate than in the other groups, which indicates the necessity to promote interest and practice of health for individuals with less interest in health.

On the basis of these results, clinicians must encourage the vaccination of current smokers and educate them about the importance of smoking cessation for vaccination efficacy. In addition, there is the necessity for further studies on how to help people improve their health status and increase vaccination rate.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.