Knowledge, Attitude, Exposure, and Future Intentions toward Exclusive Breastfeeding among Universiti Sains Malaysia Final Year Medical and Dental Students

Article information

Abstract

Background

Breastmilk is the best nourishment for an infant for the first 6 months of life. Health professionals like medical doctors and dentists can help promote and support exclusive breastfeeding. We aimed to assess knowledge, attitudes, exposure, and future intentions toward exclusive breastfeeding among final year medical and dental students at Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kelantan, Malaysia.

Methods

A total of 162 students participated in this cross-sectional study that was conducted between May and September of 2015. Self-administered questionnaires were used to collect the variables of interest.

Results

Most students knew exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for the first 6 months of life (98.1%). However, some students incorrectly thought formula milk can be given if the infant appears hungry after having been breastfed (61.7%). Additionally, some incorrectly thought expressed breastmilk can be warmed on direct heat (47.5%) and left-over expressed milk can be re-stored (60.5%). Most students agreed that exclusive breastfeeding is easier to practice than formula feeding and that it is the best choice for working mothers. Most students (93.2%) intend to breastfeed their children, and this intention was significantly associated with their experience being breastfed as infants and attitudes toward exclusive breastfeeding.

Conclusion

Generally, final year medical and dental students have favorable attitudes and future intentions toward exclusive breastfeeding, although some of them lacked knowledge about certain important aspects of the practice. Past experience of being exclusively breastfed and a more positive attitude toward the practice were associated with their future intentions to practice exclusive breastfeeding.

INTRODUCTION

Breastmilk is the ideal food for infant feeding. Breastmilk contains the essential nutrients, vitamins, and antibodies that are important for the optimal growth, development, and health of an infant. Breastmilk also contains a diverse mixture of bioactive components that influence the immune system of an infant by facilitating development, tolerance, and an appropriate inflammatory response, in addition to providing necessary protection [1]. Hence, exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life, defined as the practice of giving an infant only breastmilk (no other food or drink, not even water), has become a global public health recommendation [2].

In response to the World Health Organization’s infant feeding recommendation, endorsed on 18 May 2002 by the Fifty-fifth World Health Assembly, widespread campaigns have been conducted to promote exclusive breastfeeding among the public [2]. However, only 38% of infants up to 6 months old between 2000 to 2007 were exclusively breastfed globally [3]. In Malaysia, the overall prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among infants under 6 months old reported in the 2016 National Health and Morbidity Survey was 47.1%, which did represent an increase from 14.5% in 2006 [4,5].

There have been several studies aimed at determining the knowledge and attitudes of university students toward exclusive breastfeeding. A study on female Indonesian university students in Perth, Australia showed that only 50% of the students had received any information regarding breastfeeding [6]. A study among university students in Nigeria found that one half of the respondents had low knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding [7]. Another study among Korean university students reported that overall breastfeeding knowledge among the students was low but their attitude toward exclusive breastfeeding was generally positive [8]. A study among Hong Kong university students by Tarrant and Dodgson [9] showed that 63% of the participants wanted their future child to be breastfed, and the students who had positive attitudes were breastfed themselves, and those who knew someone who had breastfed were more likely to have this intention themselves.

Health professionals like medical doctors and dentists can help promote and support exclusive breastfeeding. Breastfeeding counselling delivered by health professionals has been shown to be effective in improving exclusive breastfeeding prevalence in countries with high rates of institutional delivery [10,11]. It is therefore important that the health professionals themselves have good knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding and positive attitudes toward the practice. Currently there is limited evidence on the knowledge, attitudes, and future intentions of local medical and dental students toward exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the same among final year medical and dental students in Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Kelantan, Malaysia. These students are the future health professionals who can help to educate and promote exclusive breastfeeding among the public.

METHODS

1. Study Design and Population

This was a cross-sectional study of final year undergraduate medical and dental students in the academic year of 2014–2015 at the School of Medical Sciences and School of Dental Sciences at Universiti Sains Malaysia, respectively. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied. During the study period, there were 175 final year medical students and 39 final year dental students. Hence, a universal sampling method was applied, and all 214 final year medical and dental students were invited to participate in this study.

2. Research Tools

A structured, self-administered questionnaire was used to collect the variables of interest. The questionnaire consisted of four parts. The first part included questions on demographic characteristics of the participants including sex, age, ethnic group, and academic program (medical or dental). The second part of the questionnaire included one question that asked about the participants’ future intentions to exclusively breastfeed and two questions on exposure to exclusive breastfeeding. Questions about exposure to exclusive breastfeeding were adapted from Tarrant and Dodgson [9]. In the original study, breastfeeding exposure was measured using three questions: whether the participants were breastfed, whether they knew anyone who has breastfed, and whether they had ever witnessed a woman breastfeeding. Although retrospective in nature, the questions were simple, direct, and clearly worded, and we did not expect any potential misclassification of exposure that may lead to recall bias. However, considering that our participants were final year medical and dental students who have completed clinical attachment at various hospital wards including a post-natal ward, we decided not to include the last question as it is most likely they had witnessed a woman breastfeeding.

The third part of the questionnaire assessed knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding. The 29-item questionnaire was developed and validated by Mohamad et al. [12] and was used with permission from the authors. The questionnaire has good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.831 [12]. Seven domains were assessed: (1) understanding on exclusive breastfeeding, (2) advantages to the infant, (3) advantages to the mother, (4) problems with exclusive breastfeeding, (5) duration of breastfeeding, (6) breastmilk expression, and (7) effective feeding. Three response options were given for each knowledge item: ‘true,’ ‘false,’ and ‘don’t know.’ Additionally, the students’ responses to all knowledge items were given scores. A score of 1 was given for each correct knowledge response, and a score of 0 was given for ‘don’t know’ and incorrect responses.

The last part of questionnaire assessed the students’ attitudes toward exclusive breastfeeding. The 11-item questionnaire was developed and validated by Che Muzaini et al. [13] and was used with permission from the authors. The overall Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.79. The responses were scored using a 4-point Likert scale from 1 for ‘strongly disagree,’ 2 for ‘disagree,’ 3 for ‘agree.’ and 4 for ‘strongly agree.’ Eight of the attitude items were negatively worded and the scoring was thus reversed.

3. Data Collection

Data collection was carried out between May and September of 2015. The students were approached during their teaching and learning sessions such as lectures, seminars, and group discussions. Prior to data collection, they were briefed on the relevance, objectives, and procedures, as well as other important information related to the study. Written informed consent was obtained from students who agreed to participate. Instructions on how to complete the questionnaires were given and the participants were asked to complete the questionnaires. All questionnaires were self-administered and anonymous. The questionnaires were collected immediately upon completion.

4. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software ver. 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics of the variables were determined using frequency and percentage for categorical data, and mean and standard deviation for continuous data. The scores for all 29 knowledge items and 11 attitude items were summed to obtain an overall score for each part. The total knowledge score ranged between 0 and 29, with higher scores indicating better knowledge, and the attitude score ranged between 11 and 44, with a higher score indicating more positive attitudes.

Factors associated with the students’ future breastfeeding intentions were determined at both univariable and multivariable levels using simple logistic regression and multiple logistic regression analyses, respectively. The following independent variables were included for testing: sex, ethnic group, academic program, past experience of being breastfed, acquaintance with someone who has breastfed, knowledge score, and attitude score.

In the multiple logistic regression analysis, all independent variables tested at the univariate level (sex, ethnic group, academic program, past experience of being breastfed, acquaintance with someone who has breastfed, knowledge score, and attitude score) were included in the variable selection procedure using the forward likelihood ratio (LR) test. Following the fit of the preliminary model, the importance of each selected variable was verified. The interactions terms were checked using the LR test. Multicollinearity problems were identified by the variance inflation factor test. The final model was assessed for fitness using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test. The classification table for sensitivity and specificity as well as the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were also obtained to evaluate the model fitness. Influential outliers were identified using Cook’s distance. Data points above 1.0 were considered influential outliers.

5. Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Human Research and Ethics Committee, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) on 20th October 2015 (USM/JEPeM/150602018). And written informed consent was obtained from students who agreed to participate.

RESULTS

From a total of 214 final year medical and dental students in the academic year of 2014–2015, 162 responded, giving a response rate of 75.7%. We did not anticipate any selection bias as the characteristics of students who participated in this study were found to be comparable with those who did not.

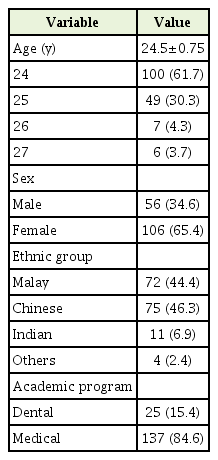

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic profile of the participants. The age of the participants ranged from 24 to 27 years old with a mean age of 24.5±0.75 years old. The majority of the participants (84.6%) were medical students, and more than half were female (65.4%). There was an approximately equal proportion of Malay and Chinese students who participated in this study.

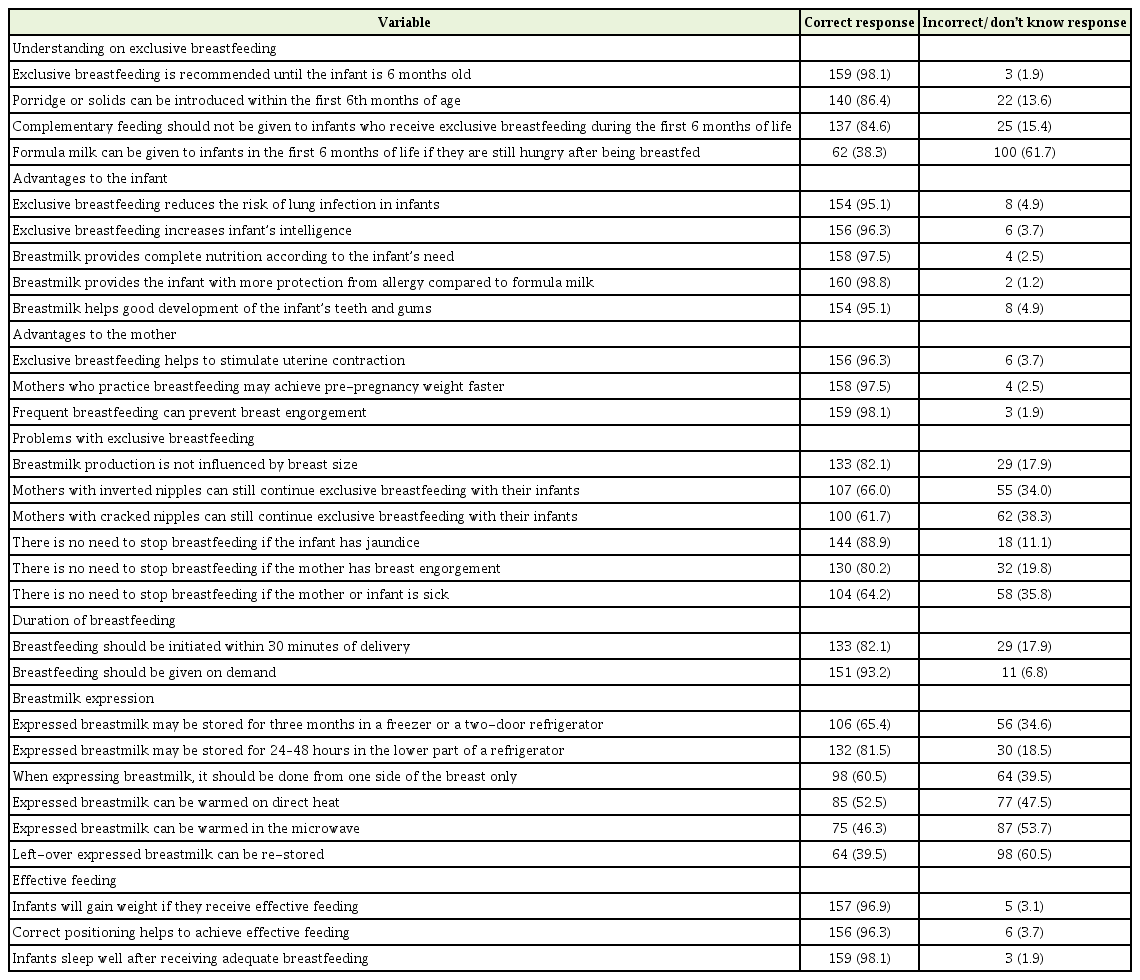

Table 2 shows the proportion of correct and incorrect/do not know responses for each exclusive breastfeeding knowledge item. The majority of the students (98.1%) knew that exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is recommended as the optimal way of feeding infants. Most students also knew about the advantages of breastfeeding to mothers and infants. However, most students incorrectly thought that formula milk can be given to infants if they appear hungry after breastfeeding (61.7%). Additionally, approximately half incorrectly thought that expressed breastmilk can be warmed on direct heat (47.5%) and in the microwave (53.7%), and leftover expressed milk can be re-stored (60.5%).

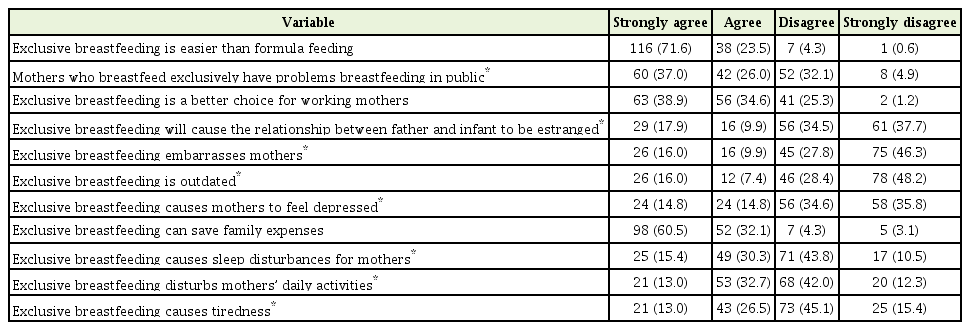

Table 3 shows the results on participants’ attitudes toward the practice of exclusive breastfeeding. The results showed that most students either strongly agreed (71.6%) or agreed (23.5%) that exclusive breastfeeding is easier to practice than formula feeding and that it is the best choice for working mothers. However, most students also either strongly agreed (37.0%) or agreed (26.0%) that mothers who breastfeed exclusively have problems breastfeeding in public.

The mean knowledge score of the participants was 23.4 (standard deviation [SD]=3.16) with a minimum and maximum score of 11 and 29, respectively, and the mean attitude score was 31.9 (SD=6.33) with a minimum and maximum score of 18 and 44, respectively. Regarding the exposure to exclusive breastfeeding, most of the participants were breastfed themselves by their mothers (81.5%) and know someone who has breastfed (92.0%). Most participants (93.2%) have future intentions for their infants to be exclusively breastfed. Factors associated with future breastfeeding intentions of the participants by simple logistic regression appear in Table 4. At the univariate level, exclusive breastfeeding intentions were significantly associated with the participants’ ethnicity, experience of having been breastfed, knowing someone who has breastfed, and attitude score.

Table 5 shows the results of multiple logistic regression analysis of factors associated with future breastfeeding intentions among the participants. At the multivariable level, experience of being breastfed and attitude score remain as factors significantly associated with future breastfeeding intentions. Participants who were breastfed themselves were about eight times more likely to have exclusive breastfeeding intentions than those who were not breastfed (odds ratio [OR], 7.99; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.99 to 32.19). Additionally, participants with higher attitude scores were more likely to have exclusive breastfeeding intentions. In particular, a 1-unit increase in attitude score will increase the odds of having breastfeeding intentions by 1.2 times (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.35). Possible two-way interactions between factors were not significant, and there was no multicollinearity problem. The fit of the preliminary final model was checked. The results of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test were not significant (P=0.210, degrees of freedom=2) and the area under the ROC curve was 0.828, suggesting that the model was fit. The overall classification results indicated correct predictions for 94.4% of the students regarding whether they have exclusive breastfeeding intentions. The contribution of each outlier was verified, and none was found to be influential.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to determine knowledge, attitudes, exposure, and future exclusive breastfeeding intentions among final year dental and medical students at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Most of the students knew that breastfeeding should be initiated within 30 minutes after delivery and the correct duration of exclusive breastfeeding is 6 months as recommended by the World Health Organization and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund [2]. However, while most students (84.6%) knew that complementary feeding should not be given to infants who receive exclusive breastfeeding, more than half (61.7%) thought that formula milk can be given to infants in the first 6 months of life if they are still hungry after been breastfed. These findings clearly indicate that most students were confused and did not truly understand the definition of exclusive breastfeeding. It is important for the relevant faculty members to directly address such erroneous beliefs and confusion since these students are future health professionals. Appropriate knowledge and skills of health workers are crucial to ensure successful breastfeeding promotion programs [10,11].

Although a large majority of the students were aware of the advantages for infants and mothers of exclusive breastfeeding, and could correctly answer items about effective feeding, some students had misunderstandings about problems concerning breastfeeding, particularly regarding nipple condition and latching. About one-third of the students thought that mothers with inverted or cracked nipples cannot continue with exclusive breastfeeding. Although having inverted or cracked nipples may make it difficult for the infant to breastfeed at first, breastfeeding can be initiated and carried through without any problem by following certain steps or simple treatments [14].

A considerable number of the students thought that there is a need to stop breastfeeding if an infant is sick. This is contrary to the current recommendation, which advises mothers to continue breastfeeding because breastmilk can protect infants against overall infections, and gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections [15]. Additionally, there is no need for mothers to stop breastfeeding if they have contracted common illnesses such as a cold, sore throat, flu, or fever. In fact, stopping breastfeeding may deprive the infants of the nutritional and potential immunologic benefits that can prevent them from contracting the illnesses [15]. However, breastfeeding is not encouraged when human immunodeficiency virus or human T-lymphotrophic virus are detected in the mothers because these microorganisms are readily transmitted through breastmilk [16]. Nevertheless, guidelines are available to help healthcare providers make informed decisions on appropriate breastfeeding practices to prevent transmission of viruses from mother to infant in cases of maternal infection [17]. Considering the important role of healthcare providers in breastfeeding promotion, misunderstanding among the students about these issues must be corrected. Inappropriate advice and discouragement from health professionals may contribute to unnecessary discontinuation of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers.

A substantial number of the students did not have correct knowledge about breastmilk expression and storage. Some students incorrectly thought that breastmilk expression should be done from one side of the breast only. About half did not know the proper procedure for using and storing expressed breast milk. Breastmilk expression and storage are important breastfeeding issues, especially for working mothers. Students’ lack of knowledge regarding these issues must therefore be rectified so that the correct information can be conveyed to patients. In addition, they must consider the challenges that working mothers may face after returning to work such as difficulty in allocating time for breastfeeding or breastmilk expression, difficulty in finding a place to breastfeed or express breastmilk, and difficulty in storing expressed milk. As future healthcare providers, the students must acknowledge the significant role they play in promoting the initiation and continuation of exclusive breastfeeding. Recommendations and encouragement from healthcare workers at birth have been shown to increase the likelihood of working mothers to practice exclusive breastfeeding [18].

In this study, most students showed positive attitudes toward exclusive breastfeeding. Most of them either strongly agreed or agreed that exclusive breastfeeding is easier to practice than formula feeding and it is the best practice for working mothers, but they also either strongly agreed or agreed that exclusive breastfeeding can be difficult in public places. Most public places in Malaysia do not have breastfeeding facilities. Fortunately, the situation is improving in recently built or developed public places such as malls, bus stations, railway stations, and airports that have designated lactation or nursing rooms. Social attitudes and legal protection of public breastfeeding also vary widely between countries. For example, certain countries in North America and northern Europe have made legislative attempts to establish the right for mothers to feed their child or pump breast milk at the workplace and breastfeed in public. However, certain Asian and African countries discourage or even criminalize public nursing [19]. A study among students in Saudi Arabia and in the United States revealed that most students (75% and 41.3%, respectively) agreed that mothers should not breastfeed in public [20,21]. In Hong Kong, a study among university students showed that while breastfeeding in public was viewed as an acceptable practice by most students (61.2%), over 80% of them believed that it would be embarrassing to mothers [9]. Embarrassment remains a challenging barrier to breastfeeding, and it is not limited to public settings. Some mothers would feel embarrassed to breastfeed in public because it will restrict their activities and this may become a reason for mothers to start formula feeding and discontinue breastfeeding [22].

The majority of the students had been exposed to exclusive breastfeeding. Most of them (81.5%) had been breastfed themselves by their mothers or knew someone who has breastfed (92.0%). Comparable findings were reported among high school students in Japan and university students in the United States, 79% and 87.5% of them respectively had been breastfed during infancy [21,23]. Most university students in the United States (91.9%) also knew someone who has breastfed. However, lower figures were reported in Hong Kong, only 30.3% of Hong Kong university students had been breastfed during infancy and only 61.4% of them knew someone who has breastfed [9].

In the current study, we found that the majority of the student respondents (93.2%) have future intentions to exclusively breastfeed their children. Encouraging results were also reported in studies among university students in Kuwait and the United States (87% and 81.7%, respectively) although a lower percentage (63%) was reported among Hong Kong university students [9,24,25]. These findings indicate that most young adults have positive attitudes toward and future intentions of practicing exclusive breastfeeding.

Our results showed that students who were breastfed as infants were significantly more likely to have intentions of breastfeeding their future children. Similar findings were reported among university students in Hongkong and the United States [9,24]. Another factor found to be associated with the student respondents’ future intentions of exclusively breastfeeding was their attitudes; the higher their attitude score, the more likely they would have such intentions. These results are also in line with previous studies done among university students, which found positive attitudes toward breastfeeding to be a significant predictor for future breastfeeding intentions [9,26]. These results highlighted the importance of inculcating correct attitudes toward breastfeeding among university students. Further studies are warranted to examine the correlations among the experience of being exclusively breastfed as infants, breastfeeding attitudes, and future intentions of practicing exclusive breastfeeding.

The influence of other variables was not significant at the multivariate level, although significant association was seen between future exclusive breastfeeding intentions and the student’s ethnicity at the univariate level. In particular, Malay students have higher odds of having future breastfeeding intentions compared to students of other ethnicities. This result is in accordance with the findings from the National Health Morbidity Survey of 2016 that showed prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding among infants below 6 months old was higher among Malay mothers (65.4%) [4]. A possible explanation for this finding is that all the Malay students were Muslims who might have perceived breastfeeding as a religious duty. Breastfeeding is strongly influenced by cultural and religious beliefs, and Islamic guidance strongly encourages mothers to breastfeed their infants for approximately 2 years [25,27]. Another variable found to be significantly associated with breastfeeding intentions at the univariate level was knowing someone who has breastfed. This finding is in agreement with the results of a study among Hong Kong University students, which showed that participants who knew someone who has breastfed were almost twice as likely to have breastfeeding intentions [9].

The findings of this study provide important insights on the knowledge, attitudes, exposure, and future exclusive breastfeeding intentions among a sample of future healthcare providers in Malaysia. We used new knowledge and attitude questionnaires that were specifically developed and validated in the Malay language among the Malaysian population. Nevertheless, the study had limitations. Information obtained through the self-administered questionnaire must be interpreted with caution due to possible bias created through favorable responses. Another limitation of this study is that our participants were students who attended their classes during the data collection period. Some of the students were not in their respective classes or sessions, and it was not possible to follow up on students who were absent owing to the anonymous nature of data collection. Additionally, some students refused to participate in the study, mainly because they were in hurry leave the class for fear of being late for the next session.

In conclusion, this study found that most final year medical and dental students in Universiti Sains Malaysia have generally favorable attitudes toward and future intentions to practice exclusive breastfeeding. However, it is also clear that some lacked understanding of some important basic facts about breastfeeding. Past experience of being exclusively breastfed and a more positive attitude towards the practice were associated with the students’ future intentions to exclusively breastfeed their infants.

Breastfeeding is on the global agenda [2], and Malaysia has implemented various policies and programs to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding. The findings of this study have highlighted the need for both medical and dental schools to address the lack of breastfeeding knowledge among students. Erroneous breastfeeding information will compromise the quality of patient care, may hinder the progress of mothers toward successful exclusive breastfeeding, and may undermine the government’s efforts and commitments to support and enhance breastfeeding practices in the country.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Universiti Sains Malaysia for providing the research funding (grant no., 304/PPSG/61313193, School of Dental Sciences, USM).