Association of Geriatric Syndromes with Urinary Incontinence according to Sex and Urinary-Incontinence–Related Quality of Life in Older Inpatients: A Cross-Sectional Study of an Acute Care Hospital

Article information

Abstract

Background

Geriatric syndromes are associated with morbidity and poor quality of life (QOL). Urinary incontinence (UI) is one of the most prevalent geriatric syndromes. However, there is little research on the association of UI and UI-related QOL with other geriatric syndromes. We investigated the relationship between geriatric syndromes and UI according to gender and UI-related QOL among older inpatients.

Methods

This study was conducted among 444 older inpatients (aged 65 years and older) between October 2016 and July 2017. We examined geriatric syndromes and related factors involving cognitive impairment, delirium, depression, mobility decline, polypharmacy, undernutrition, pain, and fecal incontinence. UI-related QOL was assessed using the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate these associations.

Results

Geriatric syndromes and related factors were associated with UI. Mobility decline (odds ratio [OR], 4.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.29–7.56), polypharmacy (OR, 3.35; 95% CI, 1.89–5.92), and pain (OR, 6.80; 95% CI, 3.53–13.09) were related to UI in both genders. Especially, delirium (OR, 7.55; 95% CI, 1.61–35.44) and fecal incontinence (OR, 10.15; 95% CI, 2.50–41.17) were associated with UI in men, while cognitive impairment (OR, 4.19; 95% CI, 1.14–15.44) was significantly associated with UI in women. Patients with depression were more likely to have poor UI-related QOL (OR, 8.54; 95% CI, 1.43–51.15).

Conclusion

UI was associated with different geriatric syndromes and related factors according to gender. Care for patients with depression, related to poor UI-related QOL, should be considered in primary care to improve the UI-related QOL of these individuals.

INTRODUCTION

Geriatric syndromes are highly prevalent, multifactorial, and associated with substantial morbidity and poor health outcomes. Geriatric syndromes include delirium, cognitive impairment, geriatric depression, fecal incontinence, mobility decline, and urinary incontinence (UI) [1]. Known risk factors of geriatric syndromes include polypharmacy, undernutrition, and pain [2]. Among the geriatric syndromes, UI is one of the most prevalent [1], and is a widespread health concern among older adults [3]. UI substantially influences individuals’ quality of life (QOL), particularly their physical, social, and psychological health status, as well as their morbidity and mortality [4]. As the elderly population grows, the number of older adults with UI is increasing along with the cost of healthcare [5].

The reported risk factors of UI include age, gender, number of childbirths, previous hysterectomy or prostatectomy, obesity, various medical problems (e.g., infection, sores, falls, fractures, physical impairment), and chronic disease (e.g., stroke, benign prostate hyperplasia, and arthritis) [6-10]. Mental problems such as low self-esteem, depression, and cognitive impairment are also associated with UI [4]. Among older adults with impaired overall function, UI is more likely to occur not only because of underlying diseases but also because of the various functional disabilities that patients have at the time of hospital admission [7,11]. Older adults who visit acute care hospitals are more likely to exhibit geriatric syndromes, such as multiple chronic diseases, impaired mobility, higher levels of dependency, and impaired cognition. These patients not only are at greater risk for a lengthy hospital stay with functional decline [12], but also deteriorating QOL [13]. Despite the dramatic influence of UI in older patients, this syndrome has remained understudied during their stay at acute care hospitals. Specifically, there is little research on the association of UI and UI-related QOL with other geriatric syndromes in acute care hospital settings. Moreover, most studies have focused on UI in women, so there is insufficient knowledge of incontinence in men. Consequently, we investigated the relationship between geriatric syndromes and UI, and how these associations differed by gender and UI-related QOL among older inpatients.

METHODS

1. Study Subjects

We enrolled 444 patients aged 65 years or older who were hospitalized between October 2016 and July 2017 in an acute care hospital. We compared the general characteristics of the two groups: with and without UI. Patients with UI were asked to complete the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) to identify the frequency, amount, and severity of UI and its impact on QOL [14]. We also examined geriatric syndromes and some of their known related factors. The institutional review board (IRB) of Konkuk University Medical Center approved this study (IRB approval no., KUH11701347) and complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before or at registration.

2. Measurements

1) Demographics and comorbidities

Demographic data, such as age, gender, insurance, body mass index (underweight, normal, overweight, and obese), and length of hospital stay, were obtained through a review of patients’ electronic medical records. Past medical history of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and experience of any surgery was also obtained by reviewing these medical records based on physicians’ diagnosis or prescription.

2) Urinary incontinence

Patients were identified as having UI if they responded affirmatively to the following diagnostic question: [15] “Have you experienced accidental urine leakage in the last month?”

3) International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form

The ICIQ-SF was completed by patients with UI to assess the frequency, amount, and severity of UI as well as its impact on QOL [14]. This instrument comprises four subscales: (1) frequency (“How often do you leak urine?”; 0, never; 1, once a week; 2, 2 or 3 times a week; 3, once a day; 4, a few times a day; and 5, always); (2) amount (“How much urine do you usually leak?”; 0, none; 2, small amount; 3, moderate amount; and 4, large amount); (3) impact on QOL (“Overall, how much does leaking urine interfere with your everyday life?”; ranging from 0 [not at all] to 10 [a great deal]); and (4) situations in which UI occurs, which comprised eight items in response to the general question “When does urine leak?” A total ICIQ-SF score ranging from 0 to 21 was calculated by summing the scores of the first three subscales. Severity of UI was categorized into five groups according to patients’ total score, as follows: 0, no symptoms; 1–5, slight; 6–12, moderate; 13–18, severe; and 19–21, very severe [16].

4) Urinary-incontinence–related quality of life

We assessed UI-related QOL using the third subscale of the ICIQ-SF. For evaluating the impact on QOL, we grouped patients according to whether they had more than 5 points: patients with 5 or more points were categorized as having ‘poor QOL,’ while patients with 4 points or less were categorized as having ‘good QOL.’

5) Geriatric syndromes and related factors

Geriatric syndromes including cognitive impairment, delirium, depression [7,11,12]. and mobility decline [7], as well as factors that are known to be related to UI [17], such as polypharmacy [2], undernutrition, pain [18], and fecal incontinence [2] were evaluated with a self-report questionnaire. We used the Korean version of the Ascertain Dementia 8-item Informant Questionnaire to assess cognitive impairment; patients having a score of over 2 points were categorized as exhibiting cognitive impairment [19]. The Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale was used to assess depression; patients who obtained a score of more than 8 points were defined as having depression. Delirium was screened using the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale, with patients scoring more than 2 points on this scale being considered to have delirium [20]. Undernutrition was evaluated using the Malnutrition Screening Test, with patients who had more than 2 points being categorized as having undernutrition. Fecal incontinence was assessed via the Low Anterior Resection Syndrome score; patients with over 2 points were classified as having fecal incontinence. Mobility decline, polypharmacy, and pain were each evaluated with a single question: “Can you walk up the stairs without assistance?” for mobility decline; “Are you currently taking five or more medications?” for polypharmacy [21,22]; and “Have you had pain more than one day in the last 2 weeks?” for pain. Answering affirmatively to each question indicated the presence of these conditions.

3. Statistical Analyses

We used a chi-square test or analysis of covariance to assess general characteristics. To determine if the association of UI with geriatric syndromes and related factors according to gender, multiple logistic regression analysis was carried out after adjusting for confounding factors such as age, length of hospital stay, and past medical history (e.g., stroke, experience of any surgery). Additionally, we conducted another multiple logistic regression analysis to evaluate the associations between geriatric syndromes and UI-related QOL, this time adjusting gender in addition to the confounding variables mentioned above. Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS statistical software ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a P-value of <0.05.

RESULTS

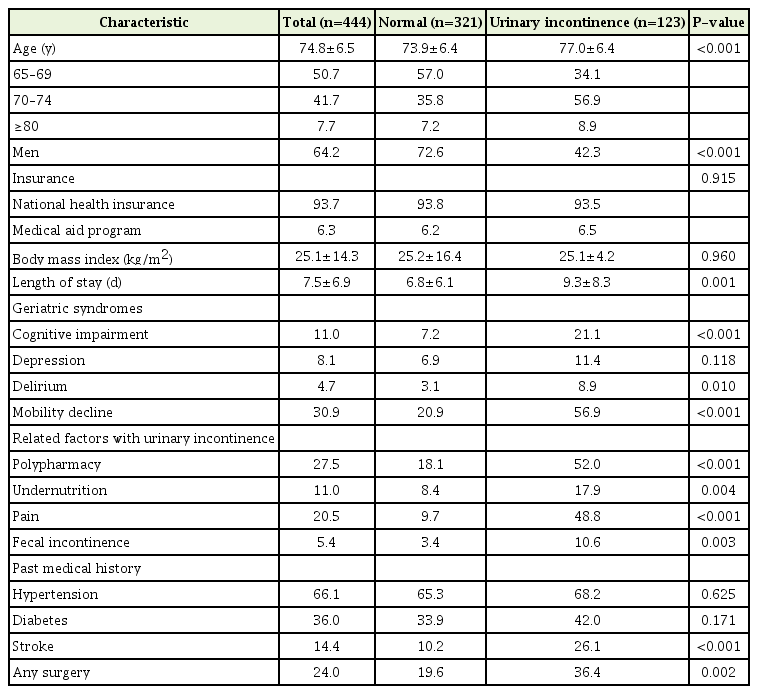

Among 444 patients, 123 reported experiencing UI in the previous 4 weeks. Table 1 shows patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. UI patients tended to be older (77.0±6.4 years versus 73.9±6.4 years, P<0.001) and have a longer hospital stay (9.3±8.3 days versus 6.8±6.1 days, P=0.001). More women had experienced UI than men (13.8% of women versus 7.0% of men, P<0.001).

The frequency, amount, impact on QOL, and severity of UI among the 123 patients with this syndrome are described in Figure 1. Out of all patients with UI, 32.5% complained of having poor QOL and 22.8% exhibited severe or very severe UI symptoms. However, the proportions did not significantly differ by gender (Figure 1).

Frequency, amount, severity, and impact on QOL of urinary incontinence (according to the ICIQ-SF). Poor QOL is defined as having more than 5 points on the question “How much does leaking urine interfere with your everyday life?” Severe UI is defined as having more than 13 points on the total ICIQ-SF score. QOL, quality of life; UI, urinary incontinence; ICIQ-SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form.

The relationship of UI with geriatric syndromes and related factors by gender are shown in Table 2. Cognitive impairment (odds ratio [OR], 2.30; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–5.05), mobility decline (OR, 4.16; 95% CI, 2.29–7.56), polypharmacy (OR, 3.35; 95% CI, 1.89–5.92), fecal incontinence (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 1.07–10.93), and pain (OR, 6.80; 95% CI, 3.53–13.09) were all associated with increased probability of having UI. Among men, delirium (OR, 7.55; 95% CI, 1.61–35.44) was a significant independent factor not found among women. On the contrary, cognitive impairment was significantly associated with UI in women (OR, 4.19; 95% CI, 1.14–15.44) but not in men. Fecal incontinence was significantly associated with UI in men, but not in women.

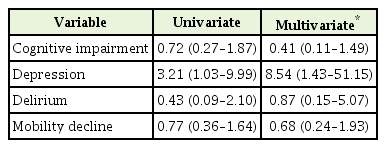

The relationships between geriatric syndromes and UI-related QOL are shown in Table 3. Cognitive impairment, delirium, and mobility decline were not associated with poor QOL. However, depression was significantly associated with poor QOL even after adjusting for age, gender, hospital stay, and past medical history (OR, 8.54; 95% CI, 1.43–51.15).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of UI was higher in women than in men; however, UI was only associated with delirium and fecal incontinence in men, whereas cognitive impairment was only associated with UI in women. Mobility decline, polypharmacy, and pain were associated with UI in both genders. The reasons for gender differences are still unclear, but one potential reason might be that men and women experience different types of UI because of the different anatomical structures of their genital organs, and these different types of UI may have distinct causative factors. Past studies on UI among men focused on its onset following surgery of the bladder or prostate; surgeries such as radical prostatectomy are a major risk factor for UI in men, along with prostatic obstruction and fecal incontinence [23]. The incidence of delirium might increase after prostate surgery, and medication use—particularly anticholinergic medication for benign prostate hypertrophy—has been recognized as a common precipitating risk factor for delirium. These are all potential explanations for gender differences related to the risk factors of UI [24].

We confirmed that the proportion of patients with UI increased with age and that they had longer hospital stays than non-incontinent patients [7]. The findings concerning the likelihood of UI increasing with the presence of cognitive impairment was consistent with results from previous studies, even though we used different definitions [25]. Research on older adults in long-term care settings has shown that impaired functional status can be a predictor of UI, which supports why decreased functional mobility is associated with UI [8]. Decreased physical activity might contribute to diminished functional mobility and voiding-related abilities, including muscle strength of the upper and lower extremities, thereby leading to pelvic floor discoordination and UI [26]. In agreement with previous studies demonstrating an association between polypharmacy and UI [26], we also found polypharmacy to be a significant risk factor for increased UI related to adverse drug events, side effects, or drug-drug interactions [1].

We further found that depression was associated with poor QOL. Both the odds of UI and poor UI-related QOL increased with the presence of depression, which is consistent with previous research [25,27,28]. Our results expand on those of previous studies, however, this study was conducted on hospitalized older patients analyzing the association between depression and direct UI-related QOL using subscales of ICIQ-SF, whereas previous studies focused on health-related QOL in community-dwelling older people [27,28]. Many patients are reluctant to seek help or medical treatment because of their perception that UI is untreatable, feelings of shame, or a fear of others knowing their problems. Because of their frequent urination, and feelings of humiliation, incontinent patients tend to avoid social gatherings, visiting friends, travel, and participation in other social activities. Withdrawal from social participation can lead to social isolation, depression, and poor QOL [29].

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, the causal relationship between independent risk factors and UI is uncertain because of the cross-sectional design. Second, this study lacks representativeness because we recruited patients from a single academic hospital. Finally, some misclassifications might have occurred because the diagnosis of UI was based on self-reported data rather than on clinical examinations.

Despite these limitations, our findings are relatively novel and indicate the need for comprehensive clinical interventions to prevent UI in patients with cognitive impairment, mobility decline, polypharmacy, pain, and fecal incontinence. Furthermore, psychosocial support is essential to relieve patients’ depressive mood and therefore improve their QOL.

Most older patients admitted to acute care hospitals have at least one geriatric syndrome. UI is a common geriatric syndrome [30], and hospitalized incontinent patients with acute illness often remain in a state of significantly reduced function even after discharge, resulting in a decrease in QOL [11]. In conclusion, this study emphasizes the necessity of supporting older incontinent patients with geriatric syndromes in acute care hospital settings. UI patients with geriatric syndromes such as cognitive impairment, depression, mobility decline, polypharmacy, pain, and fecal incontinence require a hospital system that fulfills their clinical needs in a better way and is equipped to identify atrisk patients early during hospitalization. This could be followed by the implementation of specific preventive or curative interventions during and after hospitalization to prevent UI and improve UI-related QOL.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no., HI16C0526).