A Case of Acute Pancreatitis: An Unusual Manifestation of Acute Q Fever

Article information

Abstract

Acute pancreatitis is a sudden inflammation affecting the exocrine region of the pancreatic parenchyma. Infectious etiologies are rare. Here we report an exceptional case of a 44-year-old woman from a rural area who was referred to our hospital with fever and abdominal pain. A physical examination revealed pale skin and epigastric tenderness. Thoracoabdominal computed tomography revealed a Balthazar score of D. Serum laboratory findings revealed hemolytic anemia, hepatic cytolysis, and high C-reactive protein level. Calcium and lipase levels were normal. There was no history of recent trauma, alcohol consumption, or drug intoxication. The diagnosis of “query” pancreatitis was confirmed by serological Coxiella burnetii positivity. Oral doxycycline 200 mg daily was initiated. The clinical evolution was favorable. To our knowledge, no association between acute pancreatitis and hemolytic anemia caused by C. burnetii was reported previously. Q fever must be considered in cases of acute pancreatitis, especially when the patient is from a rural area or has a high-risk profession.

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP), a sudden inflammatory condition affecting the exocrine parts of the pancreatic parenchyma, is an unpredictable and potentially fatal disease. The two most common causes of AP are gallstones and alcoholism, whereas medication, metabolic disturbances (hypercalcemia and hypertriglyceridemia), and infections are rare etiologies [1]. In a systematic review by Zilio et al. [2], the incidence of AP associated with infectious agents, including viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi, was 18% (range, 2%–35%).

Here we present a rare case of an AP caused by Coxiella burnetii.

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old rural Tunisian woman from Sahel (Mahdia) was admitted to our internal medicine department with fever and abdominal pain. She had no relevant medical or surgical history. There was no history of recent trauma, alcohol intake, or drug intoxication. She had been in contact with livestock (goats, sheep, and cattle).

The physical examination revealed: conjunctival jaundice, pallor, fever (39°C), normal blood pressure (110/70 mm Hg), tachycardia (heart rate, 98 bpm), dyspnea (respiratory rate, 32 breaths/min), and epigastric tenderness on palpation. Laboratory serum findings were as follows (Table 1): hemolytic anemia with a low hemoglobin level; high total and direct bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase levels; a positive direct antiglobulin test result for immunoglobulin G (IgG); a normal leukocyte count; moderate thrombocytopenia, hepatic cytolysis, and cholestasis; and a high C-reactive protein level with normal lipase, amylase, creatinine, calcium, triglyceride, and albumin levels.

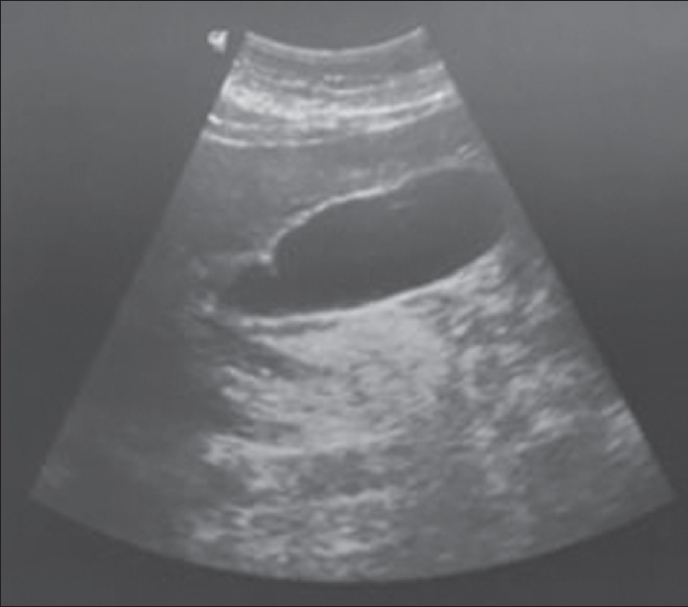

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a tumorous gallbladder without lithiasis and a normal biliary tree, liver, and pancreas (Figure 1). A thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan resulted in an Balthazar score of D (Figure 2).

Serologies for hepatitis A, B, and C; Chlamydia pneumoniae; Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Rickettsia were negative. An indirect immunofluorescence analysis revealed a significant increase in the titers of immunoglobulin M and IgG antibodies specific to C. burnetii. Therefore, we described doxycycline 200 mg once daily for 14 days.

The outcome was favorable; the patient remained afebrile and her symptoms regressed within 2 days. She was discharged on the 8th day of admission (under doxycycline treatment for 6 additional days) after significant clinical and laboratory improvements were noted. During the ambulatory follow-up, the patient presented with complete resolution of symptoms and biochemical results.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

DISCUSSION

Gallstones and alcoholism are the two most frequent etiologies of AP, reported in 39%–44% and 17%–25% of cases, respectively. Approximately one-fifth of the cases remain idiopathic [2]. Other factors such as drugs, hypertriglyceridemia, and benign or malignant strictures of the pancreatic duct are also reportedly associated with AP, but at small percentages. Infectious agents account for approximately 18% of all AP cases [2]. Indeed, infections by parasites (Toxoplasma, Cryptosporidium, Ascaris), viral agents such as mumps virus, hepatotropic virus, coxsackie virus, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, and bacterial pathogens including Mycoplasma, Legionella, Salmonella, and Leptospira can cause AP [3]. A systematic review by Imam et al. [4] showed that viruses were the leading cause of infection-related AP (65.3%), followed by helminths (19.1%). Only 12.5% of infectious pancreatitis cases are attributed to bacterial agents. Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi are responsible for 25% of bacterial pancreatitis cases [4]. However “query” pancreatitis is very rare and was first reported in 1999 in a 29-year-old French woman [5].

Q fever is a zoonosis with a variable geographical distribution worldwide. It is caused by an obligate intracellular gram-negative bacterium called C. burnetii.” The main reservoirs of this bacterium are domestic ruminants such as cattle, sheep, and goats. Birth products contain the highest concentrations of C. burnetii; however, bacteria are also found in the urine, feces, and milk of infected animals. The infection is mainly transmitted to humans via the inhalation of aerosols from the parturient fluids of infected animals. This pathogen is endemic to every part of the world except New Zealand [6]. In Tunisia, we do not have recent statistics, but seroepidemiological surveys in 1993 demonstrated that 26% of blood donors had anti C. burnetii antibodies [7]. People in rural areas who are in contact with livestock animals, especially during animal birthing activities, such as shepherds and farmers, and other professions such as veterinarians, abattoirs, dairy workers, and laboratory personnel working with C. burnetii are at an increased risk of infection by this bacterium.

The clinical manifestations of Q fever, which can be acute or chronic, are often mild or subclinical. However, these symptoms vary greatly from patient to patient, and severe symptoms due to C. burnetii have been reported in several cases [8].

This broad variation can lead to delayed diagnosis. Self-limiting flulike syndrome, pneumonia, and hepatitis are the most common manifestations of acute Q fever. Many other clinical manifestations are possible, such as maculopapular or purpuric exanthema, pericarditis and/or myocarditis, meningitis and/or encephalitis, polyradiculoneuritis, optic neuritis, and erythema nodosum [8].

In our case, the diagnosis of acute query pancreatitis was based on a bundle of epidemiological, clinical, and biological arguments (rural origin, contact with animals, fever, hepatic cytolysis, and thrombocytopenia).

The hemolytic anemia presented by this patient was also caused by the C. burnetii infection. Severe hemolytic anemia has been reported in several other cases [9].

To date, the pathophysiology of AP in Q fever has not been elucidated. However, many theories have been formulated to explain the mechanism by which other intracellular bacteria can cause AP, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae [10].

To our knowledge, an association between AP and hemolytic anemia caused by C. burnetii has not been reported previously. Since it is a worldwide zoonosis, the diagnosis of Q fever must be considered in human cases of AP, especially when the patient is from a rural area, has contact with livestock animals, or has a high-risk profession, such as veterinarian, abattoir or dairy worker, or laboratory personnel.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.