Understanding the Turning Point of Patients with Diabetes

Article information

Abstract

Background

The patient’s intention to engage in diabetes care is the hallmark of role acceptance as a health manager and implies one’s readiness to change. The study aimed to understand the process of having the intention to engage in diabetes care.

Methods

A qualitative study using narrative inquiry was conducted at a public primary care clinic. Ten participants with type 2 diabetes of more than a 1-year duration were selected through purposive sampling. In-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured protocol guide and were audio-taped. The interviews were transcribed and the texts were analyzed using a thematic approach with the Atlas.ti ver. 8.0 software (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

Results

Three themes emerged from the analysis. The first theme, “Initial reactions toward diabetes,” described the early impression of diabetes encompassing negative emotions, feeling of acceptance, a lack of concern, and low level of perceived efficacy. “Process of discovery” was the second overarching theme marking the journey of participants in finding the exact truth about diabetes and learning the consequences of ignoring their responsibility in diabetes care. The third theme, “Making the right decision,” highlighted that fear initiated a decision-making process and together with goal-setting paved the way for participants to reach a turning point, moving toward engagement in their care.

Conclusion

Our findings indicated that fear could be a motivator for change, but a correct cognitive appraisal of diabetes and perceived efficacy of the treatment as well as one’s ability are essentially the pre-requisites for patients to reach the stage of having the intention to engage.

INTRODUCTION

Patient participation and engagement in healthcare is a major contributing factor to optimum disease control, particularly in chronic diseases such as diabetes [1]. Diabetes is considered a pandemic issue [2] as the number of cases is rising significantly worldwide [3] and is the leading cause of cardiovascular death in South East Asian countries including Malaysia [4]. Patients with diabetes are not only required to comply with the medications but have to fully engage in many aspects of self-care [1]. The patients’ readiness to self-manage should be a cause of concern as managing diabetes requires the integration of a healthy lifestyle and adjustment to daily routines [5-7]. There has been a growing interest among scholars to assess the extent to which patients are ready to engage in their care. The emergence of several tools such as Patient Activation Measure and the Health Behavior and Stages of Change Questionnaire have made it possible for clinicians to differentiate patients who are ready and not ready to actively engage in healthcare [8,9].

This issue is pertinent as current evidence points toward a link between patients’ engagement and improvement in clinical outcomes, particularly glycemic control [10,11]. On the contrary, patients who were not engaged in care were found to be passive and not ready to change [5,8]. Several factors contributed toward the patient’s engagement, including the belief system, education level, locus of control, social support, psychological distress, and self-efficacy [7,12-15]. These findings reported from previous work sparked curiosity on how the actual process of change happened as it was considered relevant to clinical practice [14]. Undoubtedly, the critical element underneath these processes of behavioral change is motivation, which moves a patient from being passive to proactive in managing diabetes [16]. However, details about the aspects of motivation to change among patients with diabetes is still scarce. Little is known about how patients’ intention to engage in diabetes care originates, as having the purpose denotes one’s readiness to accept the responsibility and acts as a starting point in the patients’ journey as health managers.

Therefore, efforts should be undertaken to understand this starting point, i.e., how patients reach the stage of having the intention to engage in diabetes care. One of the useful approaches, in this regard, is an exploratory method which allows a more in-depth understanding of people’s experience in their context as well as cultures [17]. This qualitative study was performed to understand how patients started to have the intention to engage in diabetes care. The understanding of these aspects could help healthcare providers develop an effective intervention strategy for patients who are passive or not ready to participate in managing diabetes.

METHODS

This qualitative study is part of a large research project, aiming to develop an intervention program for patients with diabetes. A narrative inquiry approach through in-depth interviews was adopted to explore their personal life stories about diabetes care [17]. Specifically, in this paper, the turning point in patients with diabetes, starting from the diagnosis until their intention to change are described. The Research and Ethical Committee of the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (IRB approval no., FF-2018-235) approved this project. All participants were explained the objective of the study and informed consent was obtained before the interviews.

1. Study Setting, Participants, and Sampling

This study was conducted in Klinik Primer PPUKM, a public university primary care center located in an urban community near Kuala Lumpur—the capital of Malaysia. Ten participants were purposively sampled to cover a maximum variation of sampling based on the following criteria: (1) able to speak Malay or English; (2) had a written diagnosis of type 2 diabetes for at least 1 year; and (3) had no cognitive or hearing impairments. Three participants were invited to participate by their clinicians in-charge, as their glycemic control was poor. Another three participants from varying age and ethnic groups were selected from the attendees of an Enhanced Diabetes Care Clinic—a special clinic in our center which caters to patients with very poor diabetic control. Three more participants (from different age and ethnicity groups) were chosen from patients attending their routine diabetes follow-up at the clinic. The last participant was recruited through her husband, who was one of the participants.

2. Data Collection

An in-depth interview was chosen as the method for data collection as it allowed the researchers to explore participants’ personal experience [17]. A semi-structured interview guide was developed to cover all essential aspects including feelings, beliefs, perceptions, and actions from the time of diagnosis until having the intention to engage. The questions in the guide were open-ended and some probing questions were asked to clarify specific issues raised by the participants. One principal researcher who is a Doctor of Philosophy student and a senior family medicine specialist conducted all the interviews. Pilot interviews were carried out first in the presence of a senior qualitative researcher to ensure the researcher’s interviewer technique was appropriate and to test the protocol guide.

After the first two interviews, the protocol guide was revised and one question was asked at a certain stage during the interview to explore what triggers the participants to start engaging in diabetes care. All of the interviews took place in a private room at the clinic and were recorded with an audiotape recorder. The interviews were conducted either in Malay or English and lasted for about 35–50 minutes. A basic demographic profile was obtained before each interview. A total of ten in-depth interviews was conducted over a period of 4 months, from August to November 2018.

3. Data Analysis

The data analysis was conducted simultaneously with the data collection. At the end of each interview, the interviewer summarized what was understood from the participants and asked them to check for any missed or inaccurate information. After the interview session ended, a debriefing session was held where the researcher wrote down a summary as well as her reflections. The interview was then transcribed and the transcript was compared with the audio recording to ensure its accuracy. The text was then transferred to Atlas-ti ver. 8.0 software (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for analysis. Subsequently, the researcher heard the audio recording and read the transcript to understand the whole data before beginning to code the text. Thematic analysis was applied and coding was done in several steps [18]. Initially, a descriptive level of coding was done to a segment of text, which was either a few phrases, one single or several sentences, or paragraphs. The research team then discussed the code labels and some parts of the text were re-coded again.

After several transcripts, an interpretative level of coding was performed; later, the codes with similar meanings were grouped together. This process continued till subthemes and themes were developed. After the sixth interview, the preliminary themes and subthemes were reviewed and discussed among the research team. Some codes were re-categorized and the subthemes, as well as themes, were further redefined. The data collection concluded at the tenth interview as the data reach a saturation point in which no new themes emerged [17]. Three themes and ten subthemes were finalized to explain how participants started to have the intention to engage in diabetes care.

RESULTS

1. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Profiles of the Participants

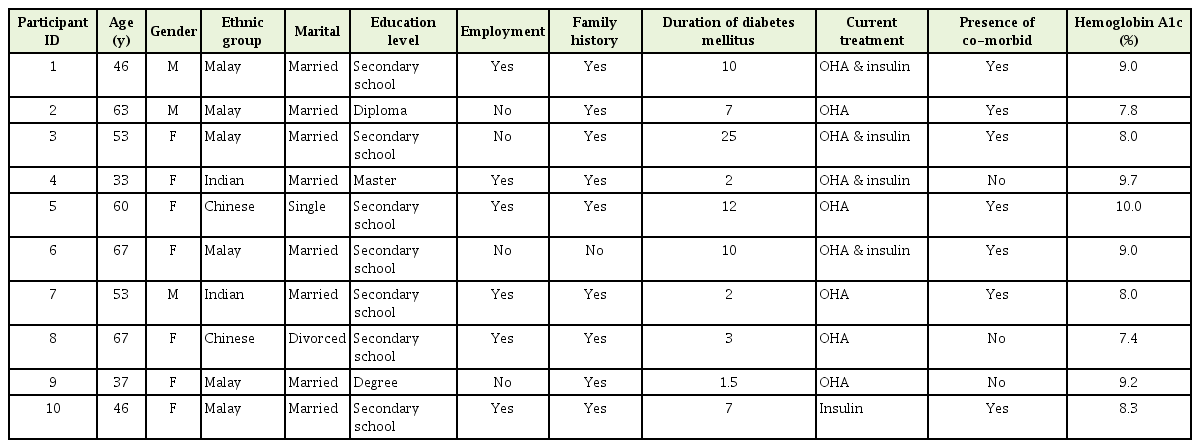

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic and clinical profile of the 10 participants. The age of study participants ranged from 33 to 67 years old. Six of the participants were Malay, two were Chinese, and two were Indians. The participants mostly had a secondary level of education and varied in their duration of living with diabetes (range, 1 to 25 years). The following three themes and 10 subthemes explained the participants’ transition from diagnosis until having the intention to change.

2. Initial Reactions toward Diabetes

During the initial period, most of the participants remembered having mixed feelings towards the diagnosis. Some of the participants felt overwhelmed and needed time to process the diagnosis. However, some were not surprised and could easily accept it.

1) Feeling low

When the participants were informed about the diagnoses, some of them felt low. In particular, one participant expressed that having diabetes made her sad as she realized that she was reaching the last cycle of her life:

“I feel sad because I never had any problem…I don’t feel comfortable with this…it made me realize that I am getting old (with a sad tone).” (Participant 6, female, 67 years old)

One participant also felt that having diabetes meant that he would need to start taking medication. He further clarified that he initially thought that the diabetes medication caused many problems; hence, he preferred to take natural supplements:

“I feel that I’m really in trouble (sighing). I really don’t want to be on medication for life. I don’t want to go through synthetic medicine; only if my blood sugar is really going off (high), then I will surrender (taking modern medications). I prefer natural (alternative) treatment because some said when they take the medicine (modern medications), they got spasm…muscle pulling…there are a lot of side effects.” (Participant 7, male, 53 years old)

One younger participant was in shock when she suddenly collapsed from septicemia as a result of her high blood sugar. She went into a depressive state as she felt her future was bleak even though she was still young. She even wished to end her life as it was becoming meaningless and she had no confidence in handling diabetes:

“I thought my life was over,...and I was frustrated that I got it at a very young age…at that time I was only 30 years old and I didn’t have any kids yet…and I know the complication of having diabetes. Before this, I had depression, I always think that I cannot go through this, I want to commit suicide, because I felt that there’s no point of living, I cannot control this (diabetes). I cannot have babies at the moment, I cannot have a normal life.” (Participant 4, female, 33 years old who is married for the second time)

2) Accepting the diagnosis

Some participants acknowledged that they need to embrace the diagnosis for a variety of reasons. An elderly participant felt that she had to accept it as the illness was a gift from God:

“I have to accept it. God has given me this illness…” (Participant 6, aged 67 years old)

Several participants emphasized the importance of accepting the illness as it would help in stabilizing one’s emotion and also in return, one would receive a blessing:

“As a servant of God, we need to accept the illness...so, I accepted it and when I did, I felt peaceful.” (Participant 7, male, 63 years old)

“If we have an illness, we need to accept it…there will be a blessing for this…” (Participant 3, female, 53 years old)

In contrast, some of the participants admitted that the diagnosis did not affect them emotionally as they were aware that the illness has a strong genetic predisposition:

“I know that diabetes runs in the family, so sooner or later, I am going to get it.” (Participant number 9, female, 37 years old)

Some also had no problem accepting diabetes as they were aware of their poor eating habits and lifestyle, as commented by one of the participants:

“I realize that this diabetes is because of my own attitude. I was too lazy to exercise, I didn’t control my food (eating habits).” (Participant 2, male, 63 years old, high body mass index)

Although the participants had accepted the diagnosis, some were not immediately willing to engage with diabetes care due to their perceptions about the disease.

3) Perceived condition not serious

During the initial phase of the diagnosis, the participants who were asymptomatic and diagnosed through blood screening felt that their condition was not bad and they were not bothered:

“I just treat it as normal, it (diabetes) doesn’t bother me that much. I don’t keep telling myself that this is so serious.” (Participant 8, female, 67 years old, diagnosed as of 3 years ago)

The participant also stated that her condition was not serious compared to other patients who were on insulin. The participant was of the opinion that those who are on insulin were more at risk of having complications as it indicated that the illness was more severe:

“I was thinking that compared to them (patients on insulin), I’m not that bad. I’m not at the stage that I’m frightened yet, in the sense that I’m not taking insulin.” (Participant 8, female, 67 years old, diagnosed as of 3 years ago)

Likewise, the younger participants confessed that in the beginning, they did not take diabetes seriously as they had no symptoms and their physical function had not yet been affected:

“At that time, I felt that as long as I can still walk (i.e., function), I had no worry. I just continue eating (sweet things) and I felt that I was still young to be bothered about diabetes.” (Participant 10, female, 46 years old, diagnosed as of 7 years ago)

It is clear to us that the participants had made an interpretation of their own conditions based on their current health status without a deep understanding of the natural progression of diabetes.

4) Controlling diabetes is beyond one’s capability

At this stage, some of the participants did not have a clear understanding of diabetes. One participant explained to some patients, diabetes cannot be cured as they believed that the outcome of the illness was already destined, hinting that a fatalistic view was still deep-rooted in our society:

“They are people who said what I can do? I got it (diabetes) already. This (diabetes) is not curable.” (Participant 8, female, 67 years old)

Moreover, a female participant claimed that a patient she knew had given up and no longer bothered with diabetes care as she could not reverse the organ complications that had already taken place. She witnessed the situation when she was admitted to the ward:

“I saw that she (the patient in the ward) was no longer bothered to care about her diabetes. I think she felt disappointed and gave up because no matter how much she tries to control, she still needs to go for dialysis.” (Participant 3, female, 53 years old)

The above statement reflected that some patients were not aware that the target organ damage could have silently occurred even before the diagnosis, as diabetes can remain asymptomatic for a long duration. If no efforts were made to clarify these negative perceptions, the patients were likely to continue disengaging and not participate in managing diabetes.

3. Process of Discovery

1) Searching for knowledge

Most of the participants expressed the need to find information related to diabetes. Although they obtained the knowledge from the doctors, a participant commented that the information was not enough.

“Sometimes, there is not enough information because all the times they (the healthcare providers) just tell you… you don’t eat things, you just take medication, I mean they have to emphasize more, like exercise… they have to give more guidelines…guidelines for us (diabetes patients).” (Participant 5, female, 60 years old, a senior clerk)

The lack of information probably led some of the participants to search for more details elsewhere, particularly from friends, family members, social media, or the Internet as mentioned by the following comments:

“I got to know from friends and relatives who also have diabetes.” (Participant 2, male, 63 years old, a pensioner)

“There is a lot of information on social media…so, we could easily know what kinds of problems can happen with diabetes.” (Participant 10, female, 46 years old)

2) Realizing the truth about diabetes

At a certain point after the diagnosis, some of the participants remembered that their perceptions of diabetes were not entirely correct. The participants gradually learned details about diabetes and started to understand the rationale of taking the medication:

“The doctor said that the decision is with me…sooner or later…this diabetes will give me some problems…like kidney problem but with the medication, it will delay the onset…maybe when I’m 60 or 70 years old.” (Participant 1, male, 46 years old)

It was during this process the participants realized that diabetes could be controlled and it was possible to minimize the negative outcome even when the disease was already at an advanced state:

“I know that this (diabetes) can be treated. If we take care…(of diabetes), at least there will be some improvement. I know that when diabetes is getting worse, we cannot expect it to be totally better but at least we can minimize it.” (Participant 3, female, 53 years old)

For some participants, the path was not easy, and they needed more time to understand what diabetes was. Few participants tried to have a conversation about it with their partners and they were comforted that diabetes could be managed. The step taken by these participants signaled to us that they needed encouragement to take responsibility for managing diabetes and some degree of knowledge among family members was beneficial:

“When I knew I had diabetes, the first person I seek advice from… is my husband as he also has diabetes. He also knows a lot than me.” (Participant 10, female, 46 years old)

One participant who initially was depressed with the diagnosis commented that her husband’s words gradually changed her negative perception of diabetes, indicating that the participant believed the person whom she trusted most:

“I hope there is no diabetes in me but my husband said that could never happen…he said I still can control, have a good reading (blood sugar level) and I can have a good healthy lifestyle. Actually, it (the husband’s words) changed me…slowly.” (Participant 4, female, 33 years old)

3) Learning through the experience

Over time, some participants were able to experience the negative side of diabetes and this certainly helped them to understand the condition better. Some of the participants reported having symptoms when their blood sugar was high:

“When my blood sugar goes up, I can feel something is not right. I will start feeling dizzy…my body would feel uncomfortable.” (Participant 3, female, 53 years old, diagnosed as of 25 years ago)

They also realized that their blood sugar level was increasingly high when they did not follow the medical advice. At this point, they started to think about managing diabetes more seriously:

“Initially, I was taking it easy but after then, when the sugar went more than about 10, 11…then I only started to take it a bit more serious. When your sugar is high, you would feel a bit of numbness.” (Participant 7, male, 53 years old, diagnosed 2 years go)

4) Emotionally affected by other people’s pain

Many of the participants recalled that they started to take diabetes seriously after seeing how other people suffered. They remembered having memories of their family members grieving from a leg amputation, blindness, and other complications. One female participant expressed her fear:

“My husband’s cousin has a wife who is diabetic, she lost her eyesight and now, the husband divorced her, so I think this thing will happen to me if I end up blind.” (Participant 4, female, 33 years old who failed in her first marriage)

A male participant felt that he would rather die than having his leg amputated as he perceived that the quality of life would diminish if he lost his physical capability and also means a lifetime suffering:

“I want to live a normal life; I don’t want to have my leg chopped and all that… I don’t want to go through that, I might as well die.” (Participant 7, male, 53 years old whose father had a leg amputation)

Another participant also was alarmed when she witnessed the consequences of ignoring the medical advice:

“My elder sister passed away already, she was only 55, she also got diabetes and loves to cook. She knows but she still doing it (ignoring the doctor’s advice). Then, one day we asked her, ‘Why is your toe (her sister) black?’ Then we take her to the hospital...in the end, they need to cut her below knees (below knee amputation), but she still didn’t make it…she died. When I saw my sister like that, I have this phobia. I don’t want to die like her…” (Participant 5, female, 60 years old with a strong family history of diabetes)

Having to see the downfall of people suffered from diabetes triggered a feeling of sadness, fear, and anxiety. They felt frightened as there is a possibility that they will end up in similar shape if they do not start to engage in diabetes care. These memories and images remain in their minds, forming as a constant reminder.

4. Making the Right Decision

After seeing how their family members were affected with diabetes, many of the participants started to evaluate their conditions and future. The fear of having complications and their concerns had made them think of the possibility to change and begin managing diabetes well. They realized that they had choices and needed to decide based on what was important to them and family.

1) Making changes to fulfil one’s own desires

Some participants conveyed their priority was to raise their family or to accomplish their own life goals. Therefore, becoming healthy was perceived as a responsibility:

“If my blood sugar is high, my body would feel very tired. I need to be fit as I need to work. I work in a factory, I cannot afford to be on medical leave because it will affect my job performance and my salary. I have to take the medication because I need to be healthy for my children, and for my work. I need to continue to live. If I get sick, who will take care of my children?” (Participant 10, female, 46 years old with children)

“Some people will say…I will fight. I want to live longer because I got so much ahead of me. I will get myself fit.” (Participant 8, female, 60 years old)

2) Making change because of others

Some of the participants mentioned that their desire to change was because they valued their loved ones. One participant acknowledged that she could only fulfil her husband’s wish if she is healthy; hence managing diabetes was seen crucial:

“I think he (the husband) sacrificed a lot, so I have to appreciate him and I must keep myself healthy and I want to have a baby for him. I can follow this diet, I want to live only for two people now, one is for my husband.” (Participant 4, female, 33 years, wishes to conceive)

Furthermore, some participants who were between 50 to 60 years old claimed that they want to maintain their physical health so that they could avoid burdening their family, particularly if they suffer from severe complications:

“When I think about it (of diabetes complications), I will try to improve…my children now have their own family to take care. Who will take care of me if I have my legs cut? I want to keep doing things by myself. I don’t want to depend on others.” (Participant 3, female, 53 years old, married with children)

“Once your health is not good, you’re a burden to yourself and then to your family. So you have to get yourself healthy.” (Participant 8, female, 60 years old, a widower)

DISCUSSION

The cornerstone of diabetes management is the patients’ commitment to self-manage but it could only be done when patients are ready and have the intention to do so [1,5]. In the process of patients accepting the responsibility, healthcare providers should be aware that patients undergo certain phases that are somewhat distinct, depending on their perceived situations. During the earlier stage of diagnosis, some of the study participants had difficulty engaging in their care as they were too overwhelmed with their emotions. Other patients with diabetes also experienced the same turmoil as they felt sad, frustrated, disappointed, resentment, and were in denial [5,7,14,19,20]. It is also worthwhile to note that the intensity of emotional distress differed among the participants with no symptoms and those with complications. In a latter situation, patients tended to be shocked and responded negatively, suggesting a longer time was needed to accept the diagnosis and responsibility [21].

The psychological reactions experienced by them were owing to their perception of the consequences posed by the illness [22], reflecting the feeling of fear and at threat after having been diagnosed with diabetes. If they perceived the danger as strong, it was likely that emotional distress will increase [22]. Our results echoed the finding from previous exploratory studies in which some patients believed that having diabetes means their longevity, social role, and future could be compromised [19,20]. The views could also be attributed to seeing their friend or family members who have diabetes, as nearly one in five adults in Malaysia is affected by this disease with an alarmingly high rate of mortality and morbidities [4]. As emotions and perceptions largely influence a person’s attitude toward a behavior [23], healthcare providers should foremost tackle these aspects first [15] as the process of accepting their role could take longer if their mental health is being affected [21]. The findings from current research also suggest that greater emotional support is needed for those who are diagnosed late or when complications have already ensued.

On the other hand, not all patients were emotionally affected and some readily accepted the diagnosis [19,20], opening a more natural path for healthcare providers to educate them on diabetes care. In this study, the patients’ acceptance was partly due to their religious beliefs and prior knowledge of diabetes. Even though religiosity has been recognized as a positive coping mechanism in patients with diabetes [24], it remains a challenge for us as some patients considered this as an excuse not to engage in healthcare [12,25]. They were adamant that the outcome of diabetes is already fated and human beings have no power to change it [12,25]. Another crucial factor in determining patients’ readiness for engagement is by having a deep understanding of the disease [5]. The adequacy of knowledge also helped in accepting the illness as some patients were able to reflect on their past actions as a cause of diabetes [20,25]. Although education is not sufficient to promote behavioral change [7], it influences a person’s beliefs and attitudes, which subsequently affect the intention to engage in a behavior. Nevertheless, at the point of diagnosis, many patients did not have an in-depth understanding of diabetes, resulting in many missed perceptions of the disease [5,12,20].

While doctors are regarded as an essential source of health information [14], some participants felt that the information was inadequate [5,20,25]. Our findings replicated a parallel observation in previous research in which patients turned to social media, the Internet, friends, and family members for more information [20]. It is probably due to the paternalistic attitude by some of the healthcare providers, causing a didactic way of learning about diabetes and as a result, the knowledge given is not tailored to the patients’ needs [14]. Providing accurate information to patients at the correct time is equally important. For instance, for those who are diagnosed early through the screening test, the diabetic educators should emphasize that patients could remain asymptomatic, but that the target organ damage can set in during this silent period and of the likelihood of avoiding complications if the disease is controlled early [1]. As opposed to patients who already have organ damage, clinicians should inform them that the efforts undertaken meant reducing the impairment and prevention of disease progression [1].

However, even when some of our participants knew about diabetes, they were still contemplating whether to engage in their care. The inability to take on the task is probably because of the lack of confidence or feeling of denial [7,14,20]. Self-efficacy plays a pivotal role in the process of patients engagement [25]. Previous researchers claimed that people with an internalist attitude had a higher level of self-efficacy and the opinion seems to agree with some of our participants [7,26]. Nonetheless, we observed that self-efficacy could be enhanced in several participants with an external locus of control. Individuals with external control tend to place other people’s opinions above theirs and this could be the reason how some of our participants’ negative perceptions toward diabetes changed. The encouraging words from their closed ones had motivated them and gradually instilled some confidence to take up their role in diabetes care. Bandura [27] also explained that social persuasion could heighten a person’s perceived ability to making a change. Considering this phase as the most challenging, healthcare providers should seek assistance from the patients’ closed social network if the patients are still at a contemplating stage.

Our study revealed that some participants were contemplating to take part in their care only after witnessing other people’s loss. As Malaysia is viewed as a collectivist culture, people in this society generally place significance in others; hence, it is likely for our participants to feel deeply affected when seeing their family members or peers suffer from diabetes complications. Their grief brought a significant meaning and had induced fear to the participants, stimulating a cognitive evaluation of their conditions. The visual images of the relatives’ or peers’ poor conditions also signaled a warning for them to take charge of their health—a phenomenon which equally happened in others with diabetes [25]. Fear is the emotional representation of a threat and participants were fast to respond when the threat was perceived as severe as well as jeopardizing their life. Previous research had highlighted the role of fear in motivating people for change [7,24,25], but too much fear can lead to an abandonment of their responsibility [28].

One more reason for the participants’ unreadiness to engage was because they probably were in the stage of ambivalence and unable to decide on whether to engage in managing diabetes, even when they knew of the negative outcome. This hesitancy was also stated in another study [19] and the participants’ ambivalence was resolved after seeing the unfortunate incident of their family members. The event also prompted them to reflect on what was important to them, and they made a decision based on their values. In general, individuals position their values based on their beliefs, life priority, and culture [29]. A collectivist society such as that of Malaysia, by and large, portrayed characteristics of inter-dependence, self-sacrificing, and putting the families’ needs ahead of themselves; these attitudes were evident among our participants when they described their life values.

Knowing an individual’s value is important as it acts as a goal and is the foundation for change [29]. Our study participants realized that there is an opportunity for them to achieve their goals by engaging in diabetes care. They would be able to maintain their family and marital ties, fulfilling their role in society, being compassionate to others by not burdening their loved ones. Having to accomplish all these were also the patients’ meaning of having a good quality of life when living with diabetes [19,20]. Recognizing this crucial information, the healthcare providers should assist patients in re-constructing their thoughts by having the correct perspectives of change, particularly the value of engaging in diabetes care. The aim is to facilitate patients in overcoming their resistance and moving them toward their goal.

1. Limitations and Strengths

The current study is limited in terms of its’ study setting. The research was done in one urban primary care clinic; therefore, the findings could not be generalized or represent the views from patients of the other setting. Nevertheless, the results gave an insight for the healthcare providers to understand the process of change, i.e., how a patient moved from not wanting to change to having the intention.

Another limitation is the study has excluded patients who could not speak English or Malay, and therefore, their reasons and process of change were not captured. As Malaysia is a multicultural and multilingual society, there is a diversity in people’s beliefs and values. However, the sampling strategies taken by the research team have incorporated those from various backgrounds, including ethnic and age groups as well as educational levels. The data analysis was done by the research team members who were from multiple disciplines including primary care, public health, psychology, and psychiatry. The different disciplines involved provides an advantage as the research topic (the process of change) is considered an interdisciplinary issue and helps to cross-validate the research findings.

2. Conclusion and Relevance to Clinical Practice

The findings from our study highlighted several essential points in the process of accepting responsibility in managing diabetes. At the initial stage, patients responded differently to the diagnosis based on their perceptions, cultural beliefs, and knowledge of diabetes. Some felt threatened up to the point of having emotional distress where others chose to minimize the condition and were not bothered. Therefore, knowing the patients’ viewpoint of diabetes is the first step for healthcare providers in helping patients to engage in their care, aiming toward modifying any negative perceptions and offering emotional support when needed.

Our results have led to the conclusion that having the right interpretation of diabetes and perceived efficacy are the salient features for having the intention to engage. Patients needed to believe in their ability to manage diabetes and that the treatment would improve the outcome. Social support could contribute to the enhancement of patients’ efficacy levels—especially when they feel emotionally overwhelmed— and also helped them to shift their focus toward the role of health managers. However, in patients who initially were not concerned, their perceived efficacies were intensified when fear sets in, indicating a feeling at risk, which in turn, triggered a decision-making process and becoming ready to take actions. Hence, the healthcare team should not dismiss the patients’ feelings of fear but instead, take patients expressing themselves as an opportunity to stimulate the thinking process and try to link life priorities as well as goals.

The other main conclusion is that there is a need for a different strategy for patients who are not ready to engage in healthcare in comparison to those who are already in the active phase. The intervention should be person-centered with a motivational approach. We also advocate further studies to assess whether “inducing fear” is a useful and practical approach in the intervention program for patients with diabetes, specifically for those who are passive and not ready to self-manage.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

The research was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients who participated in this research.