Validation Study of Korean Translated Systemic Clinical Outcome Routine Evaluation-15 as Self-Report Family Assessment Measure: Focusing on Adolescent in Daegu and North Gyeongsang Province

Article information

Abstract

Background

Systemic Clinic Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE-15) is a compact scale that contains the most critical family function assessment tools including assessments of the strengths, adaptability, and communication among family members. It has been translated into other languages in the United States and Europe. This study aimed to verify the reliability and validity of SCORE-15 with a small research population and justify its applicability in Korea.

Methods

SCORE-15 is a self-reporting family function measurement tool for each family member over the age of 11 years. This study used the Family Communication Scale (FCS) included in the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (FACES) IV package and FACES in FACES-III to verify the validity of the Korean-translated SCORE-15. Cronbach’s α value was calculated to check the reliability of SCORE-15. Data were analyzed using STATA ver. 15.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The study analyzed the correlation between FACES-III and SCORE-15 and FCS and SCORE-15 so that there was a significant static correlation in both comparisons (r=0.72 and r=0.81, respectively). Also, the research compared each subscale to analyze the correlation and the range was 0.47 to 0.95. The total SCORE-15 Cronbach’s α value was 0.92 and those values of the subscales for family strengths, family communication, and family difficulty were 0.89, 0.73, and 0.87, respectively (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Our study was the first to validate the Korean SCORE-15, which can be used as an appropriate short-form indicator for evaluating family function and changes in detecting therapeutic improvements in Korea.

INTRODUCTION

Dealing with illness is associated with the adaptability to life events and healthy families, who have better functioning style, are able to adjust better or overcome it easier. Understanding a patient’s emotional state and social situation, including physical problems, provides many advantages whenever a patient visits a primary care physician. A tool is that makes it possible to evaluate functional factors, including emotional problems undiagnosed by imaging finding such as X-ray, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, within a short outpatient consultation time (5–10 minutes) is required [1].

Family members have the biggest influence over a patient’s emotions [2]. That’s why it is crucial to build up a desirable home environment for their developmental stages and behavioral patterns [2,3].

In order to assess a patient’s emotional factors decisively affected by their familial relationships, we need to initially implement a family relationship assessment. Many researchers have conducted family function assessments to examine the relationship among family members and each patient. Recently authoritative reviews also stated the most widely used self-reported measuring tools for studying cases of couples and family therapy research. The tools are as follows: the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD); Circumplex Model Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (FACES); Beavers Systems Model Self‐Report Family Inventory (SFI); Family Assessment Measure III (FAM III); Family Environment Scale (FES); Family Relations Scale (FRS); Systemic Therapy Inventory of Change (STIC); and Systemic Clinical Outcome Routine Evaluation (SCORE) [4,5].

However, some of these measurement tools were developed decades ago and they have low reliability and validity for evaluating the functions of modern family [6].

The FACES tool developed by David H. Olson in 1991, the world’s most commonly used tool, was based on the Circumplex Mode l in 1979. This tool has been developed and revised for more than 30 years as the FACES series (I, II, III, and IV). In 1978, the original measurement tool was a 111-item instrument that was shortened to 50 items and 30 items. A third version, FACES-III was revised with 20 items in 1985 and FACES-IV in 2011 comprised of 62 items [7]. The FACES series is used in more than 1,200 dissertations and research papers [8]. FACES-III is easy to investigate, but it does not include a measure of family communication [9]. Good communication skills are the most important aspect, to solve problems between individuals as a primary intervention which reinforces the importance of studies on the types of home communication [10]. Olson and Goral [11]. developed the FACES-IV package, as a family assessment tool to overcome the shortcomings of the previous version, FACES-III. However, there are many items in FACESIV to fill out in a short time [11]. Besides it is difficult to apply them to elderly patients and those who did not establish a good relationship with their doctor. In Korea, the studies using the FACES series as a research tool use FACES-III to simply assess family functions rather than FACES-IV [8].

SCORE was based on the Clinical Outcomes and Routine Evaluation studied by Evans et al. [12] in 2000, which assessed family functions. The tool has 40 items to assess the sensitivity of changes in family functions following family therapy by the British group, in which Peter Stratton played a key role. Later in 2010, Stratton et al. [13] introduced the 15-item instrument, as the ‘most practical version for clinical use,’ and the United Kingdom has frequently used this tool to evaluate family function after psychotherapy. Since then, it has been translated into other languages in the United States and European countries, where its reliability and validity have been verified and used in clinical practice [12-14]. SCORE has currently six main versions (SCORE-40, SCORE-15, SCORE-28, SCORE-29, child SCORE-15, and relational SCORE-15). SCORE-15 is a compact scale that contains the most critical family functional assessment tools including assessment of the strengths, adaptability, and communication among family members, and it consists of a small number of questions that can increase the ease of investigation in various areas [14]. The purpose of this study was to verify the reliability and validity of SCORE-15 with a small research population and justify its applicability in Korea. In this study, SCORE-15 was translated into Korean for the first time according to the translation guidelines.

METHODS

1. Measures

The questionnaire consisted of 54 items: gender, age, birth order, family type, parents’ divorce or remarriage experience, parents’ educational background, parent’s job, total family income, daily average conversation time with parents, Korean version of Olson’s family adaptability and family solidarity assessment scale, Korean version of the Family Communication Scale (FCS), and the Korean translated SCORE-15. The study divided family types into nuclear families and large families.

The occupations of parents surveyed by the 7th Korean Standard Occupational Classification were managers; professionals and related workers; clerks; service workers; sale workers; skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers; craft and related trade workers; plant-machine operators and assemblers; elementary occupations; and others (including the unemployed) [15]. The total income of the family was: less than 2 million won, more than 2 million won to 4 million won, more than 4 million won to 6 million won, more than 6 million won to 8 million won, more than 8 million won to 10 million won, and more than 10 million won. Time spent with each parent (father or mother)-child communication on the weekdays was classified with: 30 minutes or less, 30 minutes to 1 hour, 1 hour to 2 hours, 2 hours to 3 hours, and more than 3 hours.

1) Systemic clinical outcome and routine evaluation

SCORE is a self-reporting family function measurement tool for each family member over the age of 11 years [13]. SCORE-15 has three dimensions: strengths and adaptability (Qs 1, 3, 6, 10, 15), overwhelmed by difficulties (Qs 5, 7, 9, 11, 14), and disrupted communication (Qs 2, 4, 8, 12, 13). It has 15 Likert scale items with two categories: negative and positive items. Among the questions, all the negative items (2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14) with ‘very well’ as 1 point and ‘not at all’ as 5 points and the total of positive items (1, 3, 6, 10, 15) with ‘not at all’ as 1 point and ‘very well’ as 5 points are counted. From these two processes, each person gets a total score from 15 to 75. If the score is divided by 15, the final score is given. A lower score indicates a high family function. Each scale (five items) can be scored by dividing it by five, whose lower score indicates a more effective family function. SCORE-15 is still in the process of being evaluated so cut-off points are being determined. The Irish non-clinical sample has an average score presented by Fay et al. [16] in 2013.

The study recruited a translation team in which six bilinguals who were familiar with Korean culture were asked to translate SCORE-15 into Korean (Supplementary Table 1). Two bilinguals (A, B) translated the original version into Korean while two other bilinguals (C, D) translated the first translated document into English. Next, the other two bilinguals (E, F) assessed SCORE-15, the original version, and the last translated set of the questionnaire to confirm their sameness.

2) Family Communication Scale, FACES-IV

This study used the FCS included in the FACE-IV package to verify the validity. The translated version of this scale was used from an analysis of the reliability and validity of the Korean version of FACE-IV’s FCS in 2012 [17]. The FCS consists of 10 Likert scale items from 10 to 50 points, where a higher score indicated better quality and quantity of family communication.

3) FACES-III

To verify the concurrent validity, this study used the Korean translated FACE-III from the master’s thesis Min [3] at Yonsei University in 1990, “Circumplex model and structural relationships among parent-adolescent communication: focusing on their adolescent children.”

Family cohesion was measured by 10 items, which included five subscales such as family emotional bond, help and discussion among family members, maintenance of boundaries among family members, sharing family leisure and friends, sharing family activities and participation in events. The scale that measured family adaptability also comprised of 10 items, including four areas: family leadership, control, discipline, and roles and rules. The FACES-III evaluation score is given from 1–5 points each for the 20 Likert scale items. Family adaptability was classified into 10–23 points (rigidity), 24–29 points (structural), 30–35 points (flexible), and 36–50 points (chaotic), whereas family cohesion was classified as 10–29 points (disengaged), 30–35 points (separated), 36–41 points (connected), and 42–50 points (enmeshed).

2. Subjects

During the 2 months from November to December 2018, students conducted self-administered surveys with face-to-face interviews by a researcher in two high schools in Daegu and two middle schools in North Gyeongsang Province. The total number of participants in the survey was 523. After the survey, the students in a single parent family, divorced or remarried one, and those who did not respond to the questionnaires, were excluded. A total of 433 (213 male and 220 female students) participants were chosen as research subjects for analyzing the data. This study was exempt from institutional review board review.

3. Validity

This study used simple regression analysis to determine an explanatory power in the validity measurement and concurrent validity to determine criterion-related validity.

4. Reliability

Reliability of the Korean-translated SCORE-15 was used with Cronbach’s α, which indicates the degree of internal consistency.

5. Statistical Analysis

The socioeconomic and general characteristics of subjects were estimated using a chi-square test. Cronbach’s α value was calculated to check the reliability of SCORE-15. Regression analysis examining the concurrent validity was conducted to validate the composition of the questions. STATA ver. 15.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) analyzed the data of the study.

RESULTS

1. Subject Characteristics

The socioeconomic and general characteristics of 433 participants in the study are as follows. The males comprised 49.19% of all participants and females comprised 50.81%. In terms of the birth order of the study, there were 177 (40.88%) firstborn participants, 51 (11.78%) middleborn subjects, and 167 (38.57%) participants were born as the youngest. Only children in each family accounted for the smallest number (n=38, 8.78%). Most family types were nuclear families (n=413, 95.38%). Four million won to 6 million won was the most common income interval (Table 1). The parental academic background was one of the subject characteristics. Only three fathers (0.62%) and four mothers (0.92%) graduated from middle school. Parental high school graduates accounted for 49.42% (father) and 44.34% (mother) whereas college graduates accounted for 46.19% (father) and 49.65% (mother). High school graduation for fathers and university graduation for mothers ranked high in parental education. The distribution of the father’s occupation were as follows: eight managers (1.85%), 31 professionals and related workers (7.16%), 54 clerks (12.47%), 67 service workers (15.47%), 36 agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers (8.31%), two craft and related trades workers (0.46%), 26 plant-machine operators and assemblers (26%), seven elementary occupations (1.62%), and 199 others including unemployment positions (45.96%). The high rate of the father’s other jobs including the unemployment indicated that participants lack the concept of job classification and sufficient understanding of their fathers’ jobs. The current employment situation of their mothers were as follows: 30 managers (6.93%), 36 professionals and related workers (8.31%), 90 clerks (20.79%), 50 service workers (11.55%), 26 sales workers (6.00%), 15 agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers (3.46%), one craft and related trades workers (0.23%), 90 plant-machine operators and assemblers (20.79%), seven elementary occupations (1.62%), and 88 others (20.32%). The survey investigated the time spent in parent-child communication per day. In the case of father-child communication, 159 participants answered more than or equal to 30 minutes and less than 1 hour, which accounted for 36.72% while 202 participants (46.65%) talked with their mothers for less than half an hour. Each mother/father-communication time was as follows: under 30 minutes (n=103, 23.79%), more than or equal to 30 minutes and less than 1 hour (n=159, 36.72%), more than or equal to 1 hour and less than 2 hours (n=101, 23.33%), more than or equal to 2 hours and less than 3 hours (n=32, 7.39%), and more than or equal to 3 hours (n=38, 8.78%) with their fathers. Two hundred and two participants talked with their mothers for under 30 minutes (46.65%), 139 for more than or equal to 30 minutes and less than 1 hour (32.10%), 55 for more than or equal to 1 hour and less than 2 hours (12.70%), 23 for more than or equal to 2 hours and less than 3 hours (5.31%), and 14 for more than or equal to 3 hours (3.23%). Many students talked with their parents for less than 1 hour (Table 2).

2. The Validity of Systemic Clinical Outcome Routine Evaluation-15

The results of the explanatory power of the individual questions in SCORE-15 to the entire question are presented in Table 3. The results showed that each question had an explanatory power from 0.33–0.60, of which items 1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 13, 14, and 15 had an explanatory power ranging from 0.33–0.48, with a relatively low explanation power compared to other questions, but were statistically significant (P<0.001). The concurrent validity of SCORE-15 was measured with FACES-III, which assesses family cohesion and adaptability, and FCS to evaluate family communication. The study analyzed the correlation between FACES-III and SCORE-15 and between FCS and SCORE-15 so that there was a significant static correlation in both comparisons (r=0.72 and r=0.81, respectively). Also, the research compared each subscale to analyze the correlation and the range was 0.47 to 0.95. The analysis results are shown in Table 4.

Item-total correlation of the Systemic Clinic Outcome and Routine Evaluation-15 through simple regression analysis (OLS)

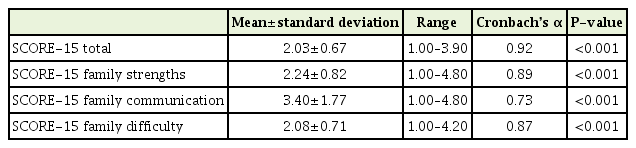

3. The Mean and Reliability of Systemic Clinical Outcome Routine Evaluation-15

Total SCORE-15 ranged from 1.0 to 3.9, with a mean number of 2.03 points and standard deviation of 0.67. The mean of the SCORE-15 subscales such as family strengths (FS), family communication (FC), and family difficulty (FD) was 2.24, 3.40, and 2.08, respectively. In this study, the total SCORE-15 Cronbach’s α value was 0.92 and those values of the subscales for FS, FC, and FD were 0.89, 0.73, and 0.87, respectively (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Most family function assessments that have been currently established are self-reported questionnaires. In general, they contain items such as family communication and problem-solving, family cohesion, family disciplines, family roles, and everyday family life. Recently, Hamilton and Carr [6] conducted a systematic review of self‐reported family assessment measures with references to the psychometric properties, clinical usefulness, and theoretical basis. The eight main tools were as follows: The McMaster FAD; Circumplex Model FACES; Beavers Systems Model SFI; FAM III; FES; FRS; and STIC; and the SCORE [17]. The purpose of this review was to examine self-reported measures to confirm their psychometric characteristics and clinical usefulness to determine the proper measuring methods for monitoring. The results showed that five family assessment scales were suitable for clinical use (FAD, FACES-IV, SFI, FAM III, SCORE) and a new scale (STIC) is currently undergoing validation. SCORE-15 has been adopted by the British Family Therapy Association and European Family Therapy Association as a tool to evaluate family therapeutic effects in families and couples [6]. Currently, SCORE-15 has been translated into English, Chinese, Czech, Dutch, Finnish, Flemish, French, German, Greek, Hindi, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Serbian, Spanish, Swedish, Transylvanian, and Welsh, and the translated version is available for download at http://www.aft.org.uk/view/15101224f1e.html. Our study conducted a Korean translation for the domestic application of SCORE-15 to assess family functions in a short period, supplementing the shortcomings of FACES-III and FACES-IV, which are the most commonly used scales in Korea. Furthermore, the reliability and validity of the SCORE-15 Korean version was assessed to help further studies and clinical practices. This study aimed to confirm the three-factor structure, reliability, and construct validity of SCORE-15 in Korea. In the reliability test of the first Korean-translated SCORE-15, Cronbach’s α was 0.92 indicating that the results was satisfactory. The result value of our study is slightly higher than two other studies, Vilaça et al. [18] in 2014 and Hamilton et al. [19] in 2015, whose Cronbach’s α was 0.84 and 0.90. According to Choi [20] in 2000, a Cronbach’s α value, when used as a tool for group comparisons, is satisfactory from 0.7 to 0.8. Also, the study stated that the value should be beyond 0.9 when clinically applied to an individual patient. Therefore, our result suggests that the Korean-translated SCORE-15 can stand out as a useful family functioning scale for routine use in clinical practice. To assess the concurrent validity of SCORE 15 in Hamilton et al. [19] in 2015, the correlation was compared with a total of five scales, ranging from 0.23 to 0.52 with a median value. The scales examined in the research were Global Assessment of Relative Functioning Scale, Strengths and Differences Questionnaire, Children’s Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, Mental Health Inventory-5, and Global Assessment of Functioning Scale [19]. We conducted a simple regression analysis in our investigation, each item of the SCORE-15 Korean version had an explanatory power of 0.33–0.60 (P<0.001). The correlation between the three-factor structure of SCORE-15 such as FS, FC, and FD and the subscales of FACES-III and IV (family adaptability, family cohesion, and FCS) verified the validation. It was also expected that the correlations between the totals on measures of family and individual adjustment with the SCORE-15 total would be as good as those with the SCORE-15 subscales, as subscales assessed aspects of family functioning rather than overall family function. It suggested SCORE-15 as more suitable for clinical use than FACES-III or IV because of the shorter administration time. Our study has some limitations such as the number of subjects, middle and high school students and adolescents among family members in a small region, which should be comprehensively considered for future studies. In particular, the impact of academic and career stressors that play a variety of roles in the case of middle and high school educated participants could not be estimated as a variable of affecting family functions in this study. However, our study was the first to validate the Korean SCORE-15. Our results will now be considered in the SCORE-28 version by researchers. The SCORE-15 index can also be conducted as an appropriate short-form indicator for evaluating family function and changes in detecting therapeutic improvements. Although the cutoff value of SCORE-15 has not been defined to determine therapeutic intervention for the improvement of family function, it has acceptable psychometric properties. Finally, our study is considerable as a family assessment instrument and as a system for providing routine feedback to physicians on therapeutic progress.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.19.0076.

SCORE-15 Korean version.