COVID-19 Patients with Mild Symptoms or without Symptom Using Residential Treatment Center Model

Article information

Abstract

Background

The rapid rise in coronavirus disease worldwide has drastically limited the availability of hospital facilities for patients. Residential treatment centers were opened in South Korea for the admission of asymptomatic or patients with mild symptoms. This study discusses the appropriateness of the admission criteria set by the centers in a pandemic situation, the prioritization of patients for admission, and ways to minimize the risk of self-isolation.

Methods

A total of 217 low-risk patients (n=217) were admitted to the Nowon Residential Treatment Center between August 22 and October 14, 2020. The following criteria were met at the time of admission: patients (1) were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms, (2) had either a controlled or no underlying chronic disease, and (3) did not need oxygen treatment. Among them, 202 patients who were eligible for inclusion in the study were retrospectively investigated through periodic interviews.

Results

Of the 202 patients, 153 satisfied the criteria for symptomatic isolation standards, and 25 for asymptomatic isolation standards. The clinical conditions of 24 patients were aggravated, and these patients were transferred to other hospitals, among which 12 had persistent fever and 13 were suffering dyspnea with oxygen saturation (SpO2) <95%.

Conclusion

In the event of another large-scale epidemic, it would be appropriate to prioritize accommodating patients who are elderly or have underlying diseases and self-isolate young patients with no underlying diseases and provide them with SpO2 meters and thermometers to self-measure SpO2 and body temperature.

INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, the novel coronavirus disease was first reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China [1]. As newly confirmed cases began to spread to other countries the World Health Organization designated the disease caused by this novel virus as “COVID-19,” which stands for coronavirus disease 2019, on February 11, 2020 [2]. The rapid outbreak occurred within a short period, subsequently causing a shortage of hospital facilities to accommodate patients in many countries around the world [3,4].

In China, the accumulated number of confirmed cases exceeded 50,000 by February 16, and on March 16, the number of confirmed cases in other countries besides China exceeded the number of confirmed cases in China [5]. In Italy, where the pandemic was prominent, by March 25, 2020, the total number of patients accumulated exceeded 70,000, and the total number of deaths had surpassed 7,000 [6]. In South Korea, an explosive outbreak occurred with no exceptions in a religious group called “Shincheonji” in Daegu, Gyeongsangbuk-do and from February 18, 2020 to March 2, 2020, the total number of accumulated patients increased from 31 to 4,212 [7].

This type of rapidly progressing pandemic leads to situations beyond society’s resources to deal with it, such as the availability of inpatient beds and intensive care unit facilities for seriously ill patients [8]. Accordingly, China converted large venues such as stadiums and exhibition halls into 14 mobile hospitals for treatment and observation of more than 14,000 suspected and confirmed patients with mild symptoms [5]. Similarly, in South Korea, to tackle the situation of an acute shortage of hospital beds, residential treatment facilities were opened with the help of large companies that converted their facilities into accommodation. Asymptomatic or mild patients were hospitalized in dormitories, while critically ill COVID-19 patients were able to use the traditional hospital beds reserved in acute care settings [9].

In addition, Seoul National University Hospital, a tertiary hospital and educational institution in Korea, converted Mungyeong Human Resource Development Center into an accommodation called “a residential treatment center,” to observe and monitor patients with mild conditions [10]. Among many residential treatment centers which subsequently became available, the Nowon Residential Treatment Center, also run by Seoul National University Hospital, set a few specific criteria for admission. While other residential treatment centers only admitted patients up to 65 years of age, no age limitation was set for this center due to the unprecedented increase in the number of patients diagnosed with COVID-19. In addition, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) results were not mandatory for discharge from the center. The decision to end the isolation was based on the clinical progress of the patients rather than RT-PCR results.

Based on the experience of the Nowon Residential Treatment Center, this paper discusses the appropriateness of the admission criteria developed by the center in an effort to maximize limited medical resources in such pandemic situations. Moreover, it discusses which patients should be prioritized during a shortage of beds. The domestic fatality rate is lower than the average worldwide fatality rate, which is related to the diagnostic rate of asymptomatic or mild patients and differences in medical resources [11]. Therefore, the effective management of asymptomatic or mild patients is thought to lower the fatality rate. The study also provides some recommendations to minimize the risk of aggravation in confirmed COVID-19 patients in the event of a spike in the number of infections, based on the various clinical experiences from the residential treatment center.

METHODS

1. Study Setting

This study was conducted at Seoul National University Hospital, a tertiary hospital and educational training institution in South Korea. The Health Promotion Center of Seoul National University Hospital opened and started to operate the Nowon Residential Treatment Center on August 22, 2020, to cope with the mass rate of infections in the Seoul metropolitan area during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Nowon Residential Treatment Center was kept open for admissions until October 14, 2020, and the overall management process replicated that of the Mungyeong Residential Treatment Center, which was operated by the Public Care Center of Seoul National University Hospital in Daegu during the massive epidemic. On the last day of the center’s operation, patients in need of long-term treatment were referred to the Taereung Residential Treatment Center.

2. Study Population

In contrast to its initial plan to limit the age of the patients who were admitted to the residential treatment center to younger than 65 years, the rapid increase in the number of those requiring medical help led them to remove the restriction on age. Patients hospitalized in the Nowon Residential Treatment Center satisfied all of the following criteria: (1) asymptomatic or mild symptoms, (2) no underlying disease or well-controlled chronic diseases, and (3) oxygen treatment not required.

High-risk patients with serious conditions were assigned to medical institutional beds and were therefore unable to enter the Nowon Residential Treatment Center. These patients met the following criteria: (1) patients with chronic underlying diseases (diabetes mellitus, chronic liver, lung, or cardiovascular disease, leukemia, or those receiving chemotherapy or taking immunosuppressants), (2) patients with oxygen saturation (SPO2) <90%, (3) patients in special circumstances (extremely obese, pregnant, on dialysis, undergone transplantation, and mentally ill).

From August 22, 2020 to October 14, 2020, a total of 217 patients were hospitalized at the Nowon Residential Treatment Center. Among them, ten patients under the age of seven were excluded from the study because of their difficulty to accurately describe their symptoms. Of the remaining 207 patients, five patients who were transferred to other residential treatment centers due to the temporary shutdown of the Nowon Residential Treatment Center, were also excluded.

The decision to discharge was based on the following clinical improvements: (1) Asymptomatic patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 could be discharged from the center if ten days had passed after the initial diagnosis without any additional symptoms. (2) Patients who had mild symptoms were discharged from the center if ten days had passed since the onset of symptoms, their symptoms improved, and had no fever without any antipyretic medications for at least 72 hours.

3. Data Collection

Data on name, sex, age, identification number, date of hospitalization, diagnosis date, address of residence before admission, underlying disease, symptom status, and types of symptoms were collected at the time of admission. At the time of discharge, data on the date, reason for discharge, address after discharge, and symptoms on discharge day were collected. Two patients were isolated together in a room, and isolated patients reported their vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, respiratory rate, and SPO2) more than twice a day. Medical interviews were conducted more than once a day by both doctors and nurses using a smartphone. Vital signs and medical interview records of the patients were stored in the health information system at Seoul National University Hospital. Chest radiography was performed at least once during admission, and a baseline chest X-ray was taken within 2 days of admission. When symptoms were suspected or a follow-up examination was required due to abnormal findings, a chest radiograph was taken in the presence of a radiologist. The Nowon Residential Treatment Center did not routinely run RT-PCR tests on patients, but only when deemed necessary.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (IRB approval no., H-2011-008-1170). The need for informed consent was waived by the participants.

RESULTS

Between August 22, 2020 and October 14, 2020, 202 eligible patients were hospitalized at the Nowon Residential Treatment Center operated by the Health Promotion Center of Seoul National University Hospital. Among them, 109 (54.0%) were women, and the mean age was 41.1 (standard deviation=15.8). Of the 202 patients, 66 (32.7%) had underlying diseases, and 38 (19.2%) presented with abnormal findings on early chest X-ray examination obtained within two days of admission. Four patients were transferred to other hospitals within 24 h of admission; therefore, X-ray data were not available for these patients. Of the total number of patients, 153 (75.7%) met the criteria for symptomatic isolation standards, whereas 25 (12.4%) met the criteria for asymptomatic isolation standards, resulting in a higher proportion of symptomatic patients at the time of admission. Twelve asymptomatic patients eventually experienced symptoms during the isolation period. Among the group satisfying the asymptomatic isolation standards, the proportions of patients aged 11–20 years, 31–40 years, and 51–60 years were the same (20% each), whereas the proportion of patients in the 51–60 years age group was relatively higher (28.1%), and the proportion of patients in the 11–20 years age group was relatively lower (7.8%) among the group satisfying the symptomatic isolation standards. Of the 202 patients admitted at the center, 24 (11.9%) were transferred, among which 10 (41.7%) had underlying diseases. Of the 178 patients who were not transferred, 56 (31.5%) had underlying diseases, which was a relatively higher proportion of patients compared to those who were actually transferred. In addition, among those who were transferred, 18 patients (75.0%) were aged 51 years or older, indicating that older patients accounted for the majority of the patients transferred (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 patients at the Nowon Residential Treatment Center according to presence of symptoms

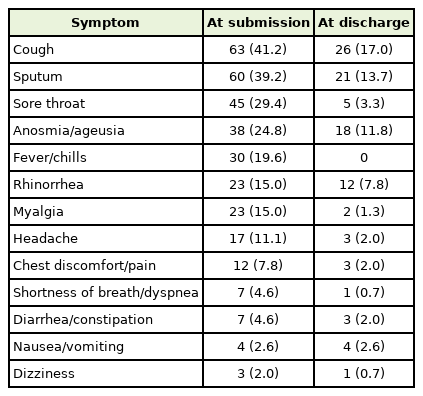

At the time of admission, the most common symptoms were cough (41.2%), sputum (39.2%), sore throat (29.4%), and anosmia (24.8%). The most common symptoms at the time of discharge were cough (17.0%), sputum (13.7%), anosmia (11.8%), and rhinorrhea (7.8%). Patients who satisfied the criteria for symptomatic isolation were usually discharged after their symptoms had been controlled (Table 2).

Clinical feature of 153 coronavirus disease 2019 patients satisfying symptomatic isolation standards at the Nowon Residential Treatment Center operated by Seoul National University Hospital from August 22, 2020 to October 14, 2020

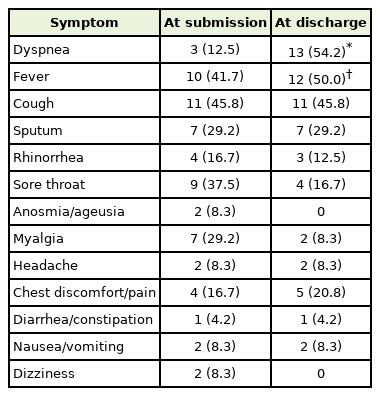

Of the 202 patients, 24 were transferred, among which 11 patients (45.8%) had a cough and 10 (41.7%) had fever at the time of admission, but at the time of transfer, 13 patients (54.2%) showed dyspnea with SPO2 <95% and 12 patients (50.0%) had persistent fever higher than 38.5°C (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted on asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 diagnosed patients aged seven years old or more, who satisfied specific criteria for admission to the Nowon Residential Treatment Center which was temporarily in operation to accommodate patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, it was necessary to increase the number of hospital facilities for COVID-19 patients, but there were limited medical resources, so it was impossible to increase the number of beds indefinitely. In addition, based on the experience of operating residential treatment centers, it was confirmed that it was not necessary to hospitalize asymptomatic or mild patients in traditional hospital facilities [12]. Most patients infected with COVID-19 develop mild symptoms and recover. Approximately 80% of patients with confirmed COVID-19 are classified as having symptoms below severe levels [13]. Therefore, it is important to quickly establish and operate a flexible facility that can temporarily serve as a subclinical facility in the event of a sudden outbreak of an epidemic.

Further, it is necessary to establish clear, administratively efficient guidelines regarding the indication of hospitalization in residential treatment centers. As of May 16, 2021, more than 7% of the total population had been inoculated with COVID-19 vaccination at least once in South Korea [14]. However, there are still more than 600 cases of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases each day. Abrupt pandemic situations may occur again at any time in the future facilitated by a number of factors. In this situation, adequate preparations are required to quickly resolve the issue of facility shortages. Nevertheless, in this study, some patients were transferred to other hospitals due to worsening symptoms. The center ran smoothly without any deaths. Therefore, it could be considered that the criteria for admission applied at Nowon Residential Treatment Center were appropriate for the distribution of patients. Based on this, these standards of admission to residential treatment centers could be recommended in the case of a COVID type pandemic in the future.

A shortage of residential treatment centers would make the prioritization of patients for admission to these centers crucial. In the Nowon Residential Treatment Center, no patient was admitted based on specific criteria; however, some were transferred to other hospital facilities due to their symptoms worsening, among which relatively older patients or patients with underlying diseases predominated, in contrast to younger patients without any underlying diseases. A study in the United States also found that the hospitalization, intensive care unit treatment, and mortality rates were the highest in patients aged 70 years or older, with or without underlying disease, compared to those in patients younger than 19 years, who showed the lowest rate. Moreover, the hospitalization rate was six times higher and the mortality rate 12 times higher in patients with underlying diseases than for those without it [15]. Accordingly, if the situation requires prioritization of patients, it may be reasonable to first admit elderly patients or patients with underlying diseases while educating young patients with no underlying diseases to closely monitor themselves.

Through this study, some recommendations could be made to reduce the risk of aggravation in patients with confirmed COVID-19 when self-isolating at home. In a pandemic situation, it is likely that there will be a shortage of available beds at residential treatment centers, thus the disease control agencies worldwide recommend self-isolation at home for seven days without immediately going to hospital when COVID-19 is suspected [16]. Among 202 asymptomatic or mild patients who entered the Nowon Residential Treatment Center, most were discharged following the improvement of initial symptoms. However, among them, some patients were transferred to other care centers or hospitals because their symptoms worsened. According to the data of the patients who were transferred to other hospital facilities, around half had persistent fever above 38.5°C, and half had SPO2 <95% and experienced breathing difficulties. Therefore, it could be recommended that providing self-isolating patients with SPO2 meters and thermometers and educating them on how to use the equipment could reduce the risk of fatal consequences. The characteristics of subclinical facilities are inevitably affected by the current status of COVID-19 outbreaks in that region, as well as by administrative and medical systems, facilities, and equipment in the country.

This was a small study that only included patients at the Nowon Residential Treatment Center; therefore, it may not represent the characteristics of subclinical facilities in South Korea. Further studies incorporating the clinical experiences of other residential treatment centers are required to set general guidelines and protocols to allocate patients to the correct medical facility to better cope with another COVID-19 pandemic in the future.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the Seoul National University Hospital promotion center staff members, police officers, public officials, and supporters for helping with the establishment and operation of the Nowon Residential Treatment Center.