|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Volume 43(6); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

The use of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (EDKA) related to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) use in people with diabetes has been increasingly reported. The causes are multifactorial, and dietary changes in SGLT2i users were observed to trigger EDKA. A ketogenic diet or very low-carbohydrate diet (VLCD) enhances body ketosis by breaking down fats into energy sources, causing EDKA. This study aimed to understand the patient specific risk factors and clinical characteristics of this cohort.

Methods

Several databases were carefully analyzed to understand the patients’ symptoms, clinical profile, laboratory results, and safety of dietary changes in SGLT2i’s. Thirteen case reports identifying 14 patients on a ketogenic diet and SGLT2i’s diagnosed with EDKA were reviewed.

Results

Of the 14 patients, 12 (85%) presented with type-2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and 2 (15%) presented with type-1 DM. The duration of treatment with SGLT2i before the onset of EDKA varies from 1 to 365 days. The duration of consuming a ketogenic diet or VLCD before EDKA onset varies from 1 to 90 days, with over 90% of patients hospitalized <4 weeks after starting the diet. At presentation, average blood glucose was 167.50±41.80 mg/dL, pH 7.10±0.10, HCO3 8.1±3.0 mmol/L, potassium 4.2±1.1 mEq/L, anion-gap 23.6±3.5 mmol/L, and the average hemoglobin A1c was 10%±2.4%. The length of hospital stay ranged from 1 to 15 days. None of the patients were reinitiated on SGLT2i’s, and 50% (2/4) of the patients reported were on the ketogenic diet or VLCD upon patient questioning.

Conclusion

Despite the popularity of the ketogenic diet and VLCD for weight loss, their use in diabetics taking SGLT2i’s is associated with EDKA. Physicians should educate patients with diabetes taking SGLT2i’s about the risk of EDKA. In addition, patients should be encouraged to include their physicians in any decision related to significant changes in diet or exercise routines. Further research is needed to address if SGLT2i’s should be permanently discontinued in patients with diabetes on SGLT2i and whether the ketogenic diet developed EDKA.

The metabolic complication, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), is mainly seen with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), but it is also observed in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1]. It occurs when insulin is deficient, and glucagon and other counter-regulatory stress hormones are increased in comparison [1]. This increases fat utilization for energy, making ketones, which leads to clinical features of hyperglycemia, ketosis, and electrolyte abnormalities [1,2]. DKA classically presents with a very high blood glucose level and dehydration, but a standard or mildly high blood glucose level can also be seen [2]. The Food and Drug Administration defines it as euglycemic DKA (EDKA) when the serum glucose level is ≤250 mg/dL with features of DKA [1].

One of the newest classes of antihyperglycemic medication approved in 2013, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), are recommended for pharmacological therapy of T2DM after the failure of, or intolerance to, metformin according to clinical guidelines [1,3]. SGLT2i targets the action of protein SGLT2i in the kidneys by preventing glucose reabsorption in the proximal renal tubules [3]. They ultimately cause glycosuria, inducing decreased insulin levels, and causes greater lipid utilization than glucose, leading to increased production of ketones [1,2]. This ketogenic state lowers the threshold for DKA, especially if there are other precipitating factors [2]. A low-carbohydrate, high-fat, or moderate protein diet, popularly known as the ketogenic diet, induces fat metabolism and urges ketosis [1]. We noticed a significant increase in the reporting of EDKA in patients who were on a ketogenic diet and SGLT2i’s. Hence, we systematically reviewed patients’ presentations, clinical features, and outcomes after developing EDKA using SGLT2i and on a ketogenic diet from the available published articles.

The relevant literature was searched to identify articles on distinguishing patient-specific risk factors and clinical characteristics of ketogenic diet-induced EDKA in patients on SGLT2i. We searched multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and Medline, to identify published literature on this topic. A detailed systematic literature search of the articles was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) protocol using the keywords but not limited to “ketogenic diet,” “very low carbohydrate diet,” “high-fat diet,” “SGLT2i,” “diabetic ketoacidosis,” “EDKA,” “euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis,” “empagliflozin,” and “canagliflozin.” The inclusion criteria were case reports published in the last 5 years between 2016 and 2021 and articles available in the English language. The exclusion criteria were duplicate articles, animal studies, studies published before 2016, and articles published in languages other than English.

The requirement for informed consent from individual patients was omitted.

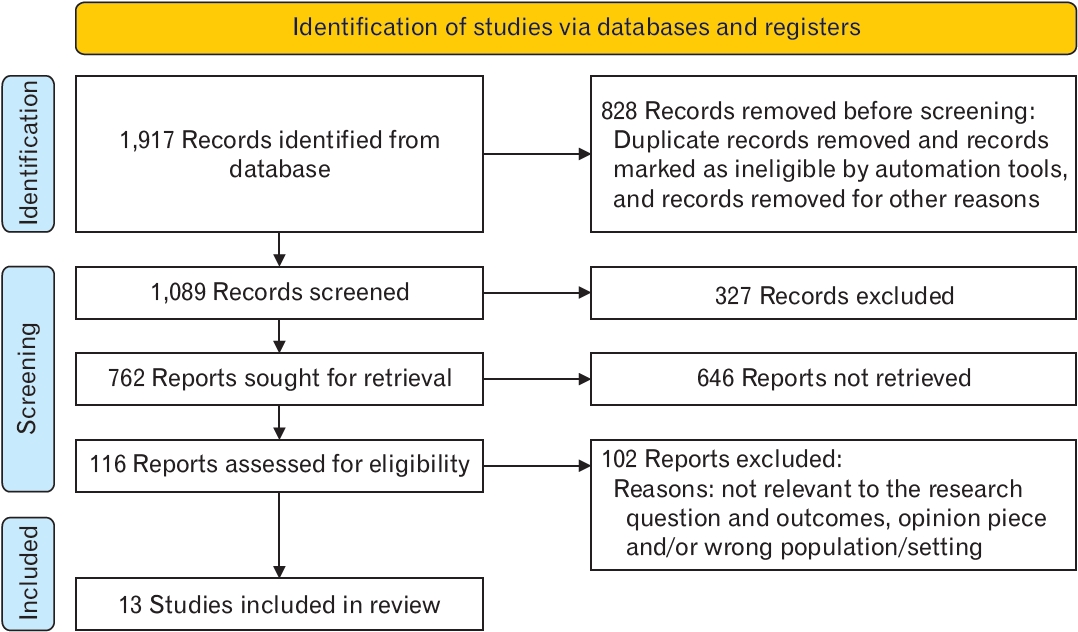

In total, 1,089 records were retrieved from the database search. After removing duplicate records, 762 were screened by title, abstract, and full-text based on eligibility criteria, of which 13 studies were included in the final review [1-13]. The details of our search results are clearly described in the PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1. All studies were case reports, as no observational studies or clinical trials were conducted on this novel topic. Most studies have been conducted in the United States, Australia, and Japan. Most studies have examined the important components of laboratory results associated with DKA when patients are admitted to emergency care. More details regarding the characteristics and laboratory values of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Thirteen case reports identifying 14 patients on a ketogenic diet and SGLT2i diagnosed with EDKA were thoroughly reviewed. Of the 14 patients, 12 (85%) presented with T2DM and 2 (15%) presented with T1DM. The duration of treatment with an SGLT2i inhibitor before EDKA onset varied from 1 to 365 days. The duration of consuming a ketogenic diet or very low-carbohydrate diet (VLCD) before EDKA onset, which varies from 1 to 90 days, with over 90% of patients hospitalized <4 weeks after starting the diet. At presentation, average blood glucose was 167.50±41.80 mg/dL, pH 7.10±0.10, HCO3 8.1±3.0 mmol/L, potassium 4.2±1.1 mEq/L, anion-gap 23.6±3.5 mmol/L, and the average hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was 10%±2.4%.

The treatment modalities mainly included supportive care with intravenous (IV) fluids, such as isotonic sodium chloride solution (NS), 5% dextrose (D5), or ringer lactate (RL) solution, along with insulin to correct metabolic acidosis and ketosis. Hourly monitoring of blood glucose and 3–4 hourly basic metabolic profile checks according to the DKA protocol are required to determine the treatment duration. Symptomatic therapy with antibiotics, such as cefepime, to control infection or intubation in cases of lethargy, increased work of breathing, and acidosis were considered. Most of the patients were started on 3 L NS, or 1 L RL bolus followed by 1 L D5. The main difference in therapy for EDKA versus ordinary DKA is the type of IV fluid provided and the insulin dosage administered. 5) The length of hospital stay ranged from 1 to 15 days. Most patients were advised against severe carbohydrate restriction or that the agent should be discontinued during the diet. So, none of the patients were reinitiated on SGLT2i’s. However, two patients reported back on the ketogenic diet or VLCD upon patient questioning.

The proximal convoluted tubule can reabsorb up to 450 g/d of filtered glucose, mainly via sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) [14]. SGLT2i is an oral anti-diabetic medication approved for T2DM. These drugs have proven efficacious, with pleiotropic effects. In a recent meta-analysis, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events associated with cardiovascular death. The most significant advantage was an associated decline in the risk for heart failure and lowering the risk for kidney failure, observed consistently across several clinical trials [15]. However, they promote ketoacidosis by upregulating glucagon secretion and limiting the available circulating glucose by promoting glycosuria and osmotic diuresis, even under normoglycemic conditions. The unavailability of glucose substrates leads to downregulation of insulin secretion. This increases lipolysis with free fatty acid production, which undergoes β-oxidation in hepatocytes, eventually forming ketone bodies. Carbohydrate restriction also promotes ketogenesis [16].

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 13 case reports, wherein 14 patients on a ketogenic diet and SGLT2i were diagnosed with EDKA. Twelve patients (85%) out of 14 had T2DM and 2 (15%) had T1DM. They were treated with SGLT2i for a varying period of 1 to 365 days before the onset of EKA. They also followed a ketogenic diet or VLCD varying between 1 and 90 days before EDKA onset, with over 90% of patients hospitalized within 4 weeks after starting the diet. At presentation, average blood glucose was 167.50±41.80 mg/dL, pH 7.10±0.10, HCO3 8.1±3.0 mmol/L, potassium 4.2±1.1 mEq/L, anion-gap 23.6± 3.5 mmol/L, and the average HbA1c was 10%±2.4%. The length of hospital stay ranged from 1 to 15 days. None of the patients were reinitiated on SGLT2i. Upon questioning four patients, two reported being back on the ketogenic diet or VLCD with their monitoring physician.

Typically, glycosuria occurs when the blood glucose concentration exceeds 225 mg/dL [4]. However, healthcare practitioners may not consider a diagnosis of DKA because blood glucose levels are normal or only slightly elevated, as also highlighted in our systematic review. Ketogenic diets, VLCD, and SGLT2i increase glucagon secretion while limiting serum glucose levels, thereby synergistically amplifying the risk of EDKA. The patient’s initially altered mental status and speech changes may be attributed to the relative depletion of intracellular and intravascular glucose stores. Similar changes in mental status in patients with alcoholic ketoacidosis have been previously attributed to intracellular hypoglycemia [5]. Besides VLCD, other etiologies of euglycemic DKA include partial treatment of DKA, decreased caloric intake, heavy alcohol use, chronic liver disease, glycogen storage disorders, and pregnancy [17]. The relative shortage of insulin among people with diabetes impedes intracellular glucose utilization, thereby exacerbating metabolic acidosis [5].

Patients with obesity, T2DM, and hypertension should be made aware of the importance of lifestyle modifications to help manage noncommunicable modifiable diseases. Healthcare practitioners need to highlight the potential risks of VLCD and a ketogenic diet when prescribing SGLT2i. Severe carbohydrate restriction should strictly be advised against in these patients, or the SGLT2i agent should be discontinued during the diet [16]. With dehydration, dyslipidemia, hyperkalemia, acute renal injury, and genital mycotic infections being recognized side effects of SGLT2i. Hence, given the potential complication of euglycemic DKA in the setting of predisposing factors, clinicians should prescribe the drug more cautiously to those at a notably higher risk for this condition [5,16]. Clinicians should brief the patients on the risk of acidosis even if the blood glucose level is not elevated, as these agents may lower the threshold for DKA. Patients may be advised to use dip-sticks for the rapid urinary analysis of ketone bodies. Early diagnosis and treatment can significantly improve morbidity and mortality rates. However, the current results have a few limitations. The study was limited by the risk of bias assessment to determine the methodological quality of the evidence from the case reports. Additionally, since the results of this manuscript are primarily based on case reports, high-quality studies, such as observational studies and randomized clinical trials, need to investigate this topic in depth.

In conclusion, despite the popularity of the ketogenic diet and VLCD for weight loss, their use in people with diabetes taking SGLT2i is associated with EDKA. EDKA poses a challenge to physicians treating ketoacidosis with normal blood glucose levels, leading to a delay in prompt treatment. Our goal is to caution clinicians that ketogenic diets and SGLT2i use, both singly and in combination, can lead to severe, life-threatening EDKA. Additionally, patients should be counseled on the importance of including their primary care physician in any decisions relating to significant changes in diet or exercise routines and should be made aware of EDKA. Further research is needed to evaluate whether SGLT2i should be permanently discontinued in patients with diabetes on SGLT2i and the ketogenic diet that developed EDKA.

Figure. 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) flow diagram for the current study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and laboratory values of included studies

| Authors | Country | Patients | Age (y) | Gender | Diabetes type | BMI (kg/m2) | Precipitant | Diet initiation before developing EDKA | Blood glucose (mg/dL) | Laboratory results | Symptoms | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinha et al. [4] (2020) | Australia | 1 | 64 | F | Type 2 | NA | Empagliflozin (10 mg) | 2 mo | 185.4 | HCO3 (NA); AG (24); serum ketone (4.7 mmol/L) | Vomiting and diarrhoea | Discharged |

| Mistry et al. [1] (2020) | USA | 2 | 47 | Pt. 1: F; Pt. 2: M | Type 2 | NA | Pt. 1: empagliflozin (25 mg); Pt. 2: canagliflozin (100 mg) | Case 1: 2 mo; case 2: 7 d | Case 1: 187; case 2: 251 | Pt. 1: HCO3 (11 mmol/L); AG (22 mmol/L); BHB (6.78 mmol/L); HbA1c (13.6%); Pt. 2: HCO3 (12 mmol/L); AG (24 mmol/L); BHB (5 mmol/L); HbA1c (8.2%) | Pt. 1: acute-onset left- arm numbness and chest pain; Pt. 2: chest pain associated with SOB | Pt. 1: discharged after 5 days of ICU stay; Pt. 2: discharged after 3 days of ICU stay |

| Sood et al. [2] (2018) | USA | 1 | 44 | M | Type 2 | 33.82 | Canagliflozin | 1 mo | 180 | Na (135 mmol/L); K (4.2 mmol/L); HCO3 (14 mmol/L); AG (19 mmol/L); BHB (75.50 mmol/L); no ketonuria | Abdominal pain | Discharged |

| Earle et al. [5] (2020) | USA | 1 | 31 | F | Type 2 | NA | Canagliflozin | 2 wk | 139 | Metabolic acidosis; Na (139 mEq/L); K (3.5 mEq/L); AG (29); urine ketones (80 mg/dL); urine glucose (500 mg/dL) | Dizziness and SOB, slurrred speech, nausea, pain radiating down the posterior aspect of both legs, and constipation | ICU for few days then discharged |

| Garay et al. [3] (2020) | USA | 1 | 44 | M | Type 2 | NA | Empagliflozin (25 mg) | 7 d | 199 | HCO3 (9 mmol/L); AG (24 mmol/L); BHB (8.89 mmol/L); no ketonuria; no glucosuria; pH (7.11); Na (132 mmol/L); K (5.5 mmol/L) | Malaise, fatigue, heartburn, and decreased exercise capacity | ICU for 16 hours then discharged |

| Latif et al. [6] (2021) | USA | 1 | 43 | F | Type 2 | NA | Empagliflozin (25 mg) | 2 wk | 169 | Serum pH (7.01); HCO3 (5 mmol/L); AG (21); glucosuria (4+); positive ketonuria | Vomiting, cough, SOB, and generalized weakness | Discharged |

| Fukuyama et al. [7] (2020) | Japan | 1 | 54 | F | Type 1 | 25.7 | Canagliflozin (100 mg/d) | 6 d | 196 | HCO3 (2.7 mmol/L); AG (24 mmol/L); pH (7.0); urine glucose (4+); urine ketones (4+); glucose (219 mg/dL); lipase (264 U/L) | Severe dyspnea | Mechanical ventilation for 24 hours then discharged after 15 days of hospital stay |

| Leys et al. [8] (2019) | USA | 1 | 46 | M | Type 2 | NA | Canagliflozin | NA | 198 | HCO3 (6 mEq/L); pH (6.91); BHB (12.6 mg/dL); AG (28); glucosuria; ketonuria | Abdominal pain, SOB, and non-bloody vomiting | Mechanical ventilation for 2 days then discharged after 15 days of hospital stay |

| Khan et al. [9] (2020) | USA | 1 | 65 | M | Type 2 | NA | Empagliflozin (25 mg) | About 1 wk | 159 | Metabolic acidosis with ketonuria and glucosuria | Nausea, headache, mild generalized abdominal pain, and chest discomfort | Discharged |

| Fieger et al. [10] (2020) | USA | 1 | 42 | F | Type 2 | 48.7 | Canagliflozin | 3 mo | 90 | BHB (73.0 mg/dL); AG (19 mmol/L); pH (7.1); pCO2 (16 mm Hg); urine ketones (80 mg/dL); glucosuria (>500 mg/dL) | Acute-onset nausea, vomiting, and SOB | ICU stay and then discharged |

| Tauseef et al. [11] (2020) | USA | 1 | 61 | M | Type 2 | NA | Empagliflozin | 3 wk | 153 | HCO3 (7 mEq/L); pH (7.11); AG (20 mEq/L); lactate (6.1 mg/dL); serum osmolarity (310 mOsm/kg H2O); BHB (>4.5 mmol/L) | Hypotension | ICU stay and then discharged |

| Richstein et al. [12] (2020) | USA | 1 | 53 | F | Type 2 | NA | Ertugliflozin | 1 wk | 104 | HCO3 (8 mmol/L); AG (22); pH (7.10); BHB (66.94 ng/mL); HbA1c (11.2%); glucosuria (≥500 mg/dL); ketonuria (80 mg/dL) | NA | Discharged |

| Castellanos-Diaz et al. [13] (2020) | USA | 1 | 70 | F | Type 1 | 20.0 | Empagliflozin (12.5 mg) | 4 wk | 136 | HCO3 (10 mmol/L); AG (27); pH (7.1); BHB (8.8 mmol/L); glucosuria (>500 mg/ dL); moderate ketonuria | Nausea and dizziness | Discharged |

REFERENCES

1. Mistry S, Eschler DC. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis caused by SGLT2 inhibitors and a ketogenic diet: a case series and review of literature. AACE Clin Case Rep 2020;7:17-9.

2. Sood M, Simon B, Ryan KF, Zebrower M. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with SGLT2 inhibitor use in a patient on the Atkins diet: a unique presentation of a known side effect. AACE Clin Case Rep 2018;4:104-7.

3. Garay PS, Zuniga G, Lichtenberg R. A case of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis triggered by a ketogenic diet in a patient with type 2 diabetes using a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor. Clin Diabetes 2020;38:204-7.

4. Sinha S, Gavaghan D, Yew S. Euglycaemic ketoacidosis from an SGLT2 inhibitor exacerbated by a ketogenic diet. Med J Aust 2020;212:46.

5. Earle M, Ault B, Bonney C. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis in concurrent very low-carbohydrate diet and sodium-glucose transporter-2 inhibitor use: a case report. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med 2020;4:185-8.

6. Latif A, Gastelum AA, Sood A, Reddy JT. Euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis in a 43-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus on SGLT-2 inhibitor (empagliflozin). Drug Ther Bull 2021;59:93-5.

7. Fukuyama Y, Numata K, Yoshino K, Santanda T, Funakoshi H. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis due to a strict low-carbohydrate diet during treatment with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. Acute Med Surg 2020;7:e480.

8. Leys LE, Oteng EK, Mallipeddi VP, Berhane F, Poddar V. Severe euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis associated with use of canagliflozin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;199:A1734.

9. Khan A, Mushtaq K, Khakwani M, Khakwani MS, Mushtaq R, Robison R, et al. Metabolic acidosis and its predisposing factor: euglycemic ketoacidosis caused by empagliflozin and low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet in type 2 diabetes mellitus: case report. SN Compr Clin Med 2020;2:1243-7.

10. Fieger EI, Fadel KM, Modarres AH, Wickham EP 3rd, Wolver SE. Successful reimplementation of a very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet after SGLT2 inhibitor associated euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. AACE Clin Case Rep 2020;6:e330-3.

11. Tauseef A, Asghar MS, Zafar M, Lateef N, Thirumalareddy J. Sodiumglucose linked transporter inhibitors as a cause of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis on a background of starvation. Cureus 2020;12:e10078.

12. Richstein R, Palmeiro C. MON-LB124 euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis on initiation of ertugliflozin in a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus precipitated by a ketogenic diet. J Endocr Soc 2020;4(Supplement_1):MON-LB124.

13. Castellanos-Diaz J, Mathews SE, Barsamyan G, Julio LC, Kadiyala S. SAT-685 euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis in T1d: the era of SGLT-2 inhibitors and keto-diet. J Endocr Soc 2020;4(Supplement_1):SAT-685.

14. Vallon V, Thomson SC. Targeting renal glucose reabsorption to treat hyperglycaemia: the pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibition. Diabetologia 2017;60:215-25.

15. McGuire DK, Shih WJ, Cosentino F, Charbonnel B, Cherney DZ, Dagogo-Jack S, et al. Association of SGLT2 inhibitors with cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol 2021;6:148-58.